(This article is originally published at Readmoo)

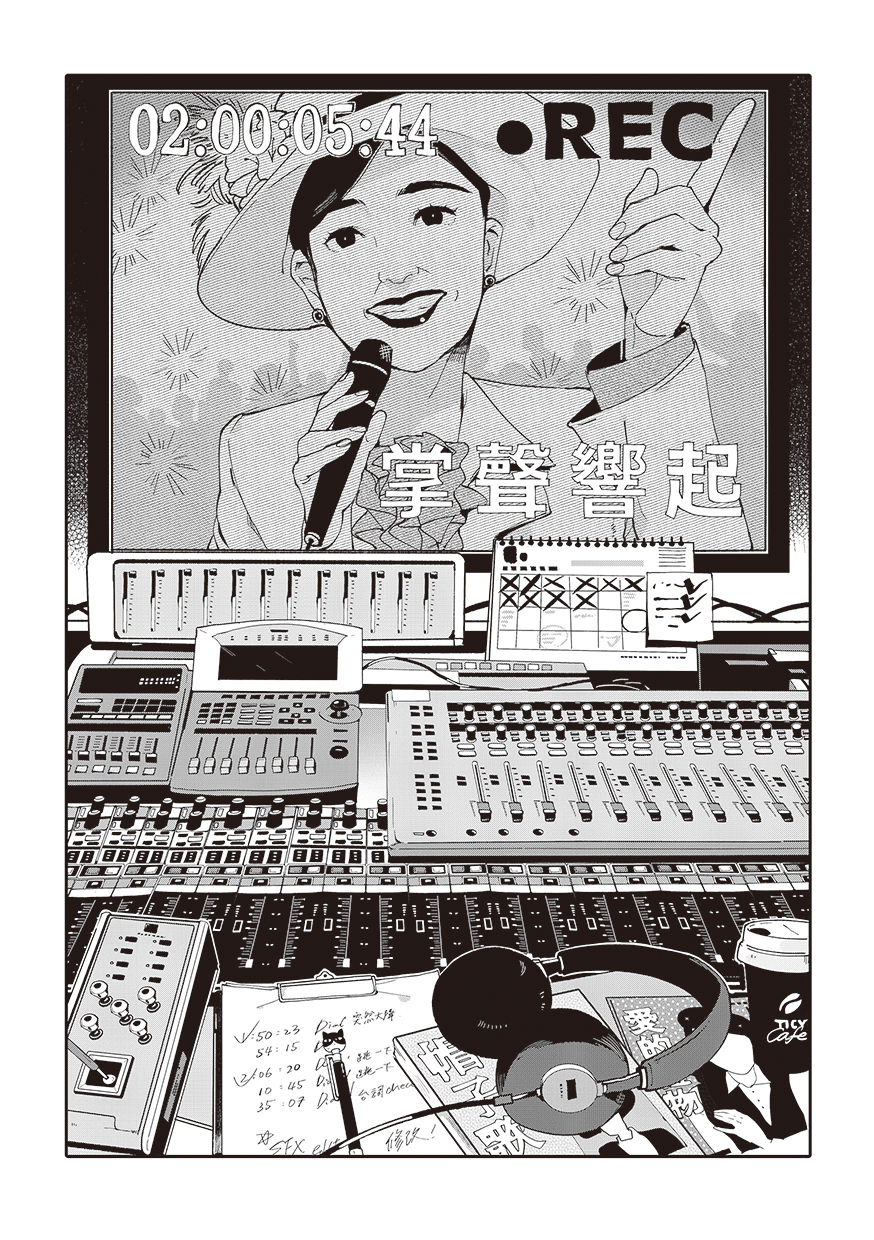

Tender Is the Night is a collaboration between comic artist Huihui and playwright Chien Li-Ying. The text version of this work, which was originally a submission to a call for scripts, also appears in Observations of a Transvestite, a collection of Chien Li-Ying’s plays. In the epilogue to that work, Chien wrote, “Sexuality is the greatest window into an individual’s behavior, the subtleties of interaction, the unfathomable depths, the shame, joy, and quotidian life all find abundant expression within sexuality. This subject has always fascinated me, and I’ve always wanted to write a play that could bring life to various forms of human sexuality, which is why I’ve included the work in this collection.”

I have always admired Chien Li-Ying’s plays and still remember the profound impact Observations of a Transvestite, had on me the first time I saw it. Later on, after reading Tender Is the Night, I remember thinking how wonderful it would be to see the play staged. Of course, in reality this would be impossible. Why? Because the play depicts nine sexual encounters playing out in nine different rooms. At least for now, a racy performance including nudity and sexual acts would probably not be allowed on Taiwan stages.

Then the graphic novel version of Tender Is the Night was published.

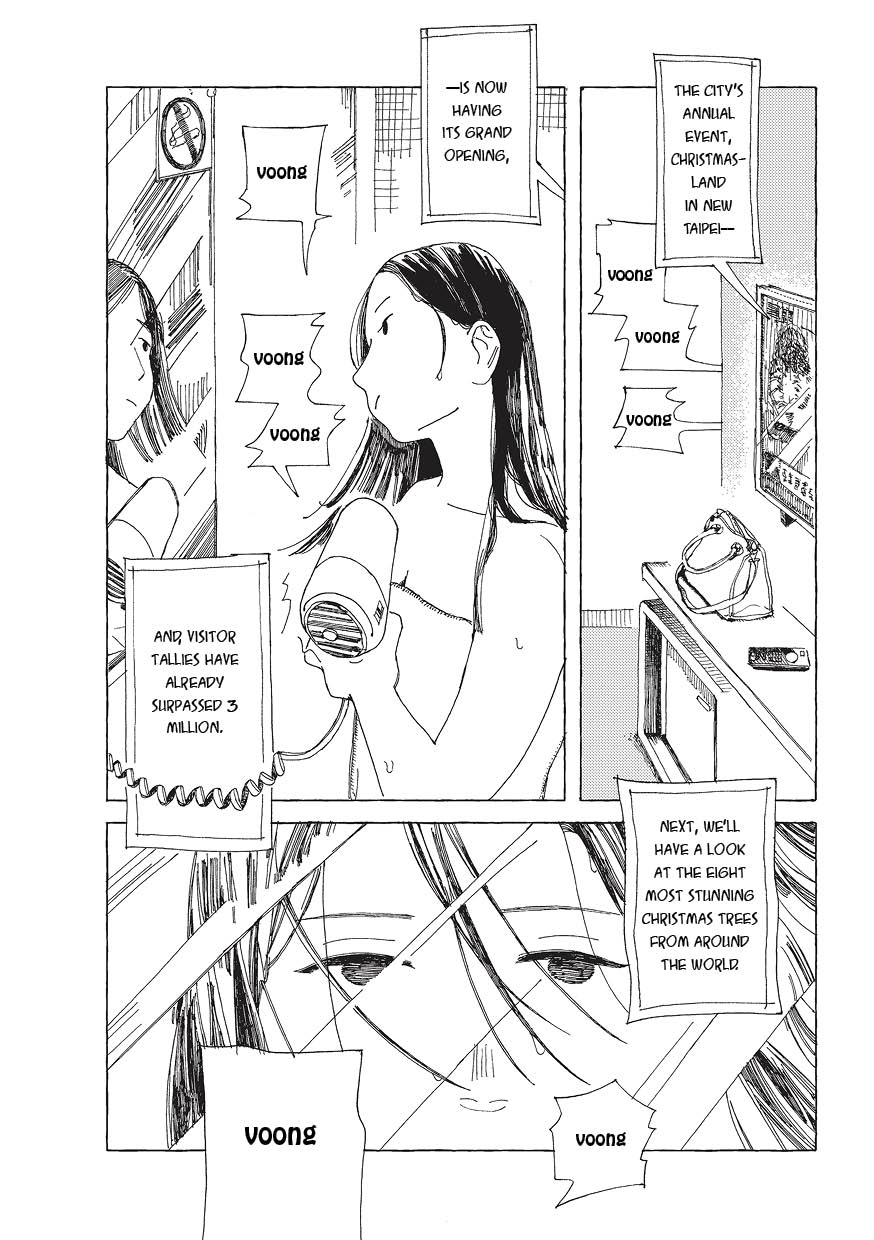

Huihui’s previous graphic novel series Blowing-Up Adventure of Me had a dedicated readership in the independent comic market. The novel follows the protagonist as she honestly confronts her own sexual timidity – in Huihui’s pictorial world, the desire and longing for intimate encounters find both gentle and ardent embodiment. With Tender Is the Night, Huihui brings Chien Li-Ying’s script to life, providing a visual representation not just of the script’s many stage changes, but also the deeper desires, and subtle expressions of alienation underlying the physical act of sex.

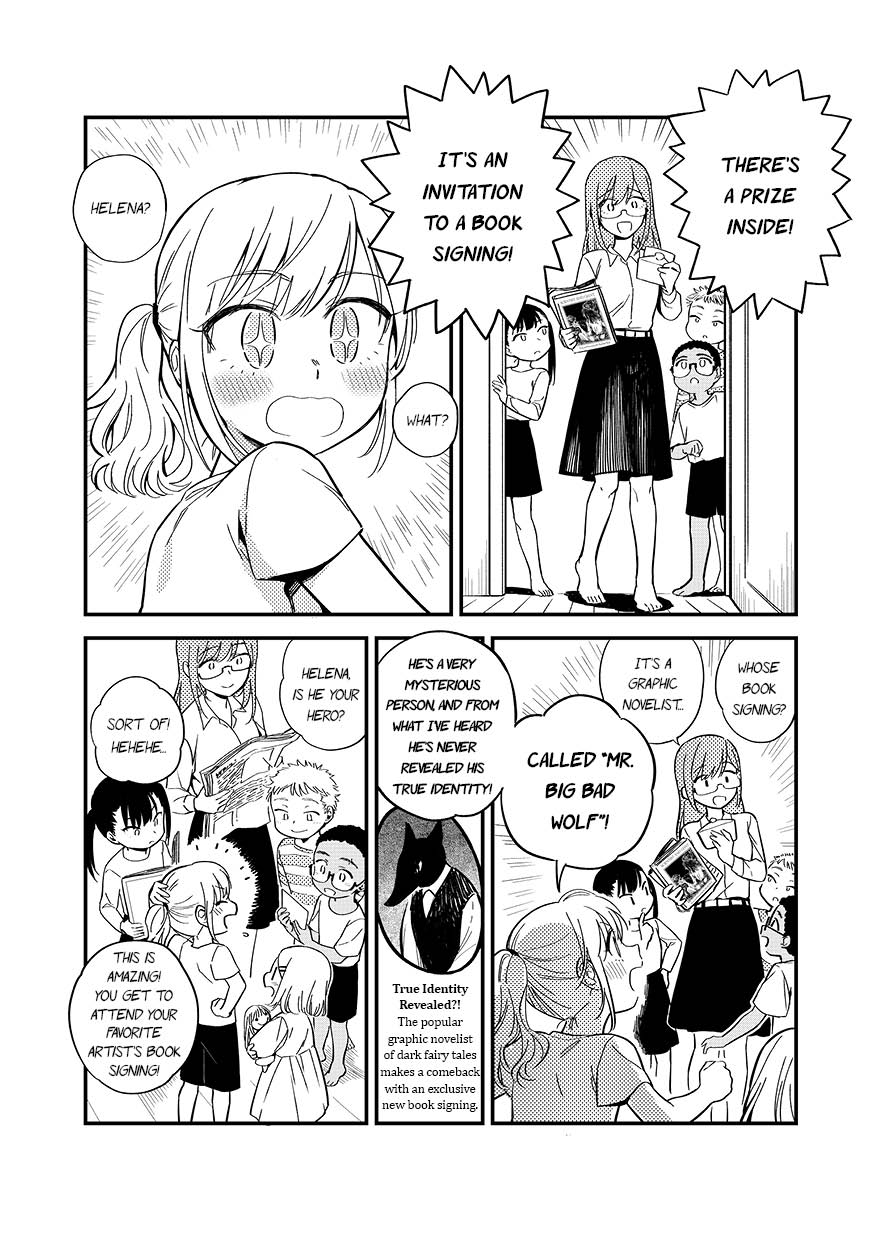

This is how the novel’s publisher, Faces Publishing describes the book: “A romantically ostracized printshop worker, a lesbian’s clandestine encounter with her wife’s paramour, a woman’s feeling of emptiness with her hearing-impaired boyfriend, a gay little person practices fellatio, an impasse between a self-abasing portly woman and her chapstick-seeking male bedfellow, and elderly illicit lovers acting as each other’s emotional anchors…with its depictions of nine physical and sexual relationships rejected by the mainstream market and its appetite for conventional stories of love and marriage, Tender Is the Night has laid the first brushstrokes of a contemporary Taiwanese ukiyo-e, an exploration of the unlimited possibilities and stringencies of gender and sexual identity.”

The nine short graphic novels that unfold in the nine different rooms of Tender Is the Night might all find a common thread in the book’s catchline: “Can you treat me like you would a normal person?” What seem like the stories of strangers are ultimately our own: even if the sexual experiences and body types of the characters differ from the reader’s, there is no sense of “other” in these 9 stories, they are narratives in which we can all find common ground. After all, who hasn’t felt the solitude, loneliness, self-abasement, masochism and longing for bodily warmth and connection experienced by the comics’ characters?

Huihui renders act upon act of sexual romance with a gentle touch, deftly attending to the minute details of every scene and carving out the fine grains of each character’s semblance and personality. Their acts of mutual longing and rejection form an exquisite engenderment of the human interactions as well as the relationships between people and sexuality captured in the original script. With scenes of lovemaking and nudity appearing every few pages, Tender Is the Night is clearly an x-rated graphic novel, but Huihui isn’t so much interested in arousing readers’ sexual desires and bodily urges as she is in stirring those deeper and more profound levels of the psyche – whether you’re a hot-blooded lover or a cold and distant recluse, as long as you’re human, chances are that deep inside you, too, wish to be loved.

What makes Tender Is the Night so enthralling is its authenticity: the sexual acts themselves and the humanity that unfolds around them all evince a sense of honesty and sincerity. There is an austere and unvarnished quality to Huihui’s storytelling, so much so that it almost seems to derive from the perspective of an indifferent bystander. Three of the nine stories involve encounters between a couple and a third person – yet, the outsiders’ perspectives often highlight the simultaneous complexity and purity of the couples’ love. In “Chapstick”, Huihui has her slightly homely female protagonist ask a man who is trying to flee from her: “Is there something wrong with me?” This blunt outburst is no doubt a symptom of her continual frustration with the judging eyes of her peers.

In the postscript, Huihui asks her readers to reflect on which of the chapters had the deepest impact on them.

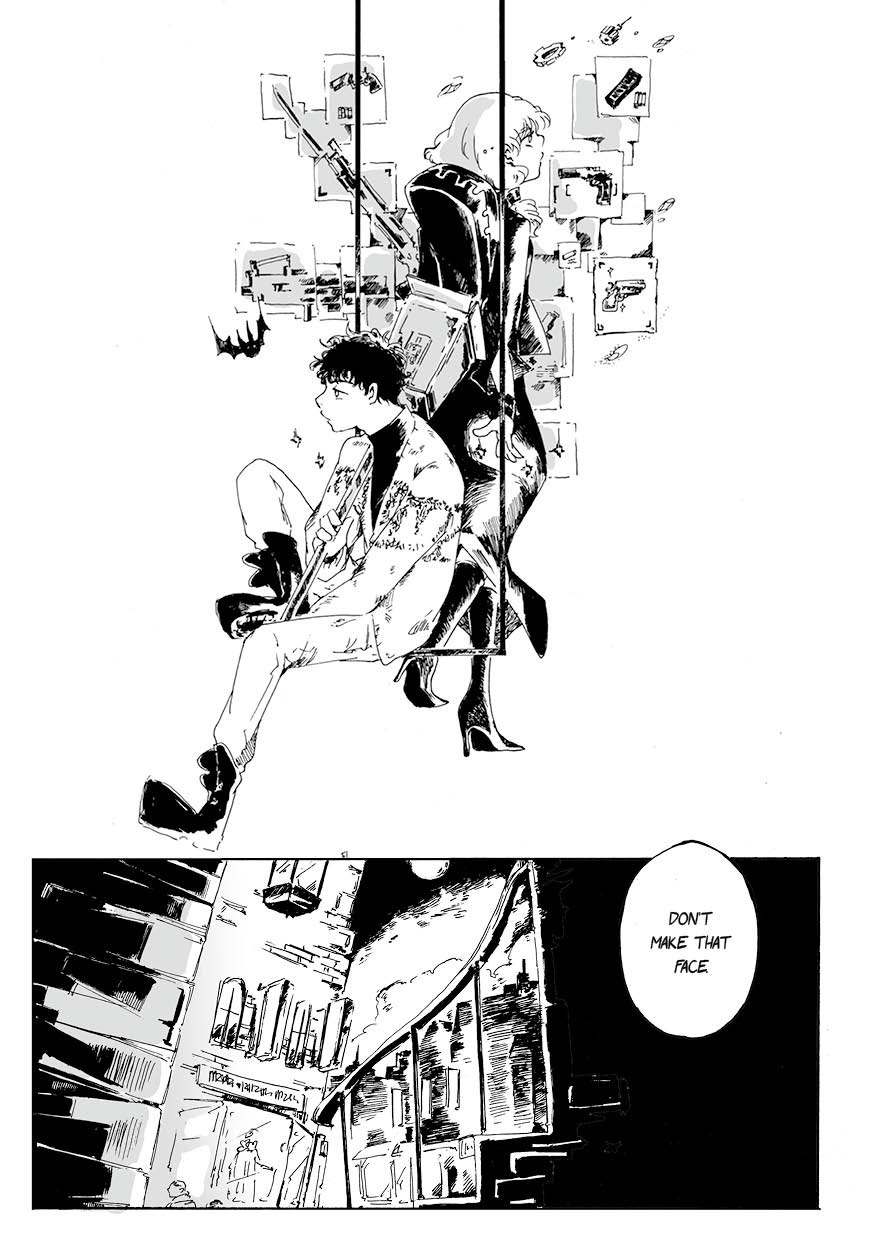

For me, it was “The Turning of the Seasons”.

In this tale of an elderly love affair, Huihui uses an identical framing for the male and female protagonist in each slide; only the background changes to reflect their peripatetic journey through a shifting series of hotel rooms. The rooms feature the standard trappings of most cheap hotels – the sprawling double bed with bedside tables on either side and the obligatory framed prints of famous western paintings. As time passes and conversations and scenery shift, so to do the selection of paintings on display. In the very last room, the painting hanging on the wall is Gustav Klimt’s famed “The Kiss”.

“The Turning of the Seasons” is short in length and, tucked as it is in the very center of the book, serves as an ellipsis that aptly separates the chapters that come before and after it. Yet, this fleeting vignette focuses on a much more profound kind of relationship. In the love and companionship of the elderly, each is witness to the most unsightly aspects of their partner, to the atrophy and wasting of their physical bodies. As such, they cling not to each other’s corporeal flesh but to the heart and soul nestled within. As they conclude their lover’s hotel rendezvous and return to their families, we see that it is these brief escapes which give them the courage to once again face reality.