(This article is originally published at Okapi)

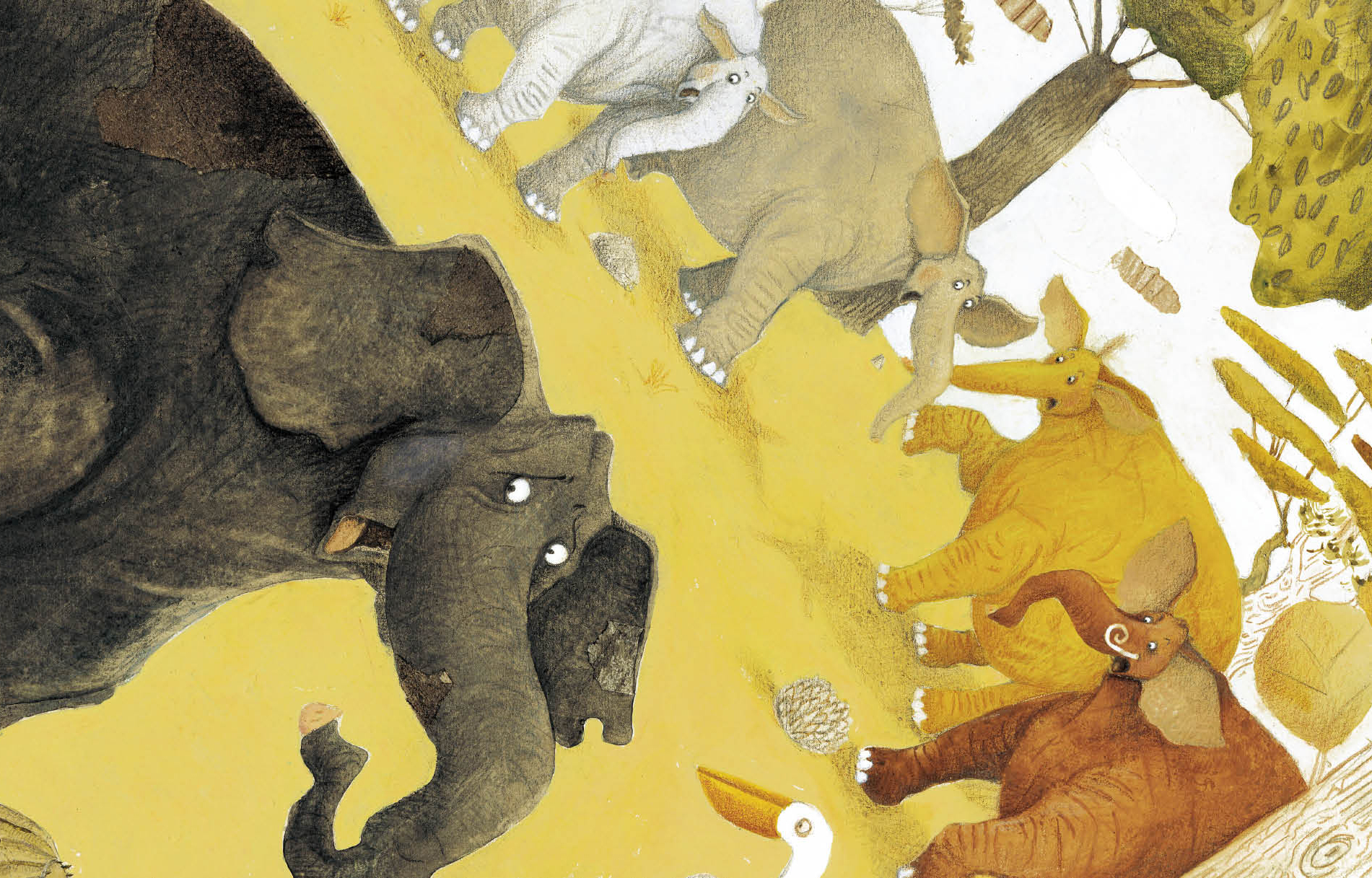

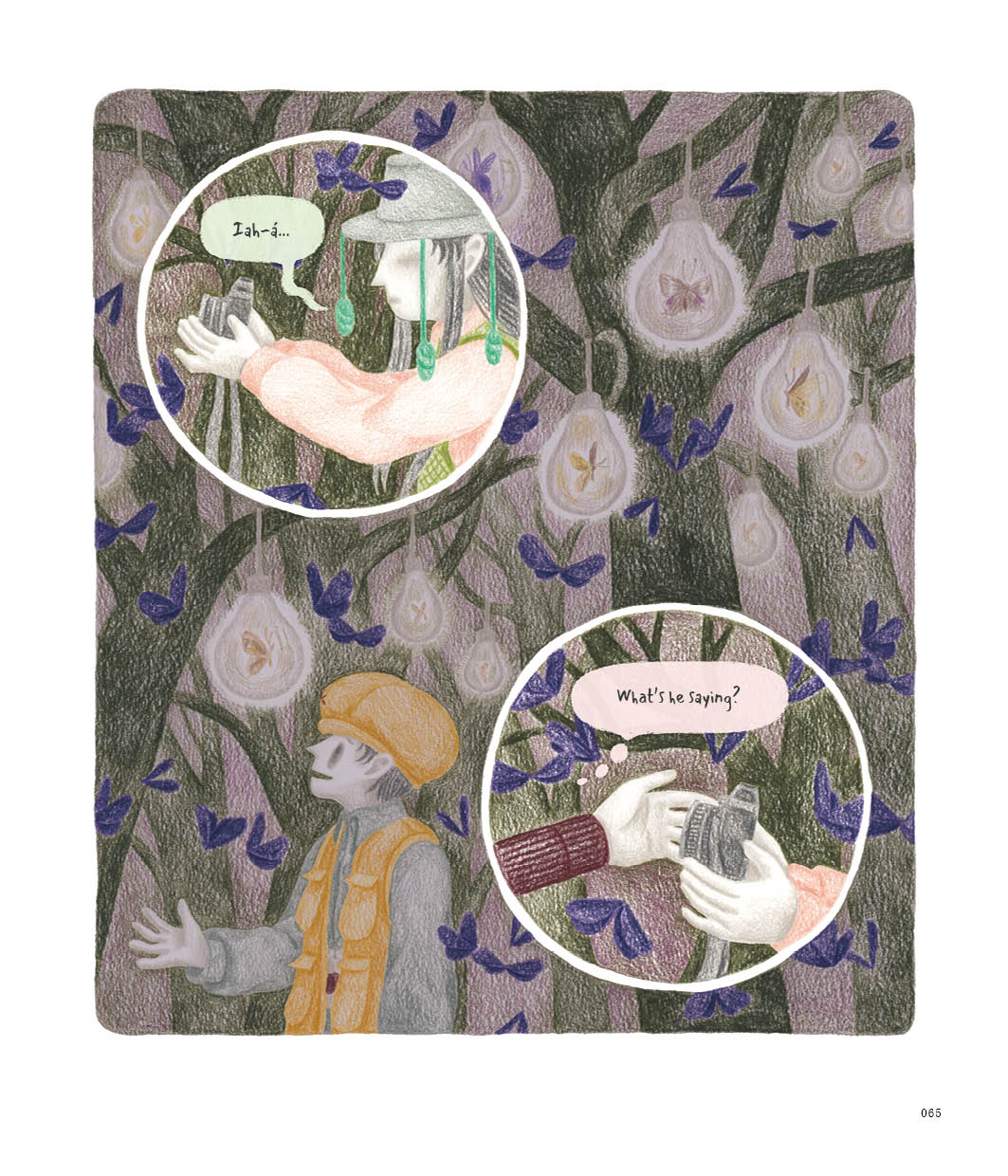

Author-illustrator Egretllu’s debut picture book, Somewhere, took him more than three years to complete while he worked at a grocery store. The patience it took to produce the story and illustrations has truly paid off, and his simple, candid drawing style reflects the subtle, warm emotions hidden beneath the surface. The “happy place” Egretllu portrays is a land of memory that’s even deeper than the sea, and the “somewhere” from the title is a spiritual space that we’re not sure if we can reach, like a dream involving love and happiness.

Somewhere is a story about how to keep on living. About keeping going after a loss, about how we keep going even when time stops and the world ends. It’s a deep, poetic and solitary read that leaves us with a slight sense of sadness and tenderness at the same time. Please enjoy the interview below where Egretllu shares his thoughts on writing and illustrating picture books.

Wu Wen-Chun: You chose to write under the pseudonym Egretllu and started a Facebook page called “Matters of Life”, then you became a picture book author and wrote Somewhere. When did you have the initial concept for Somewhere? And what did you find was the biggest challenge during the long creative process?

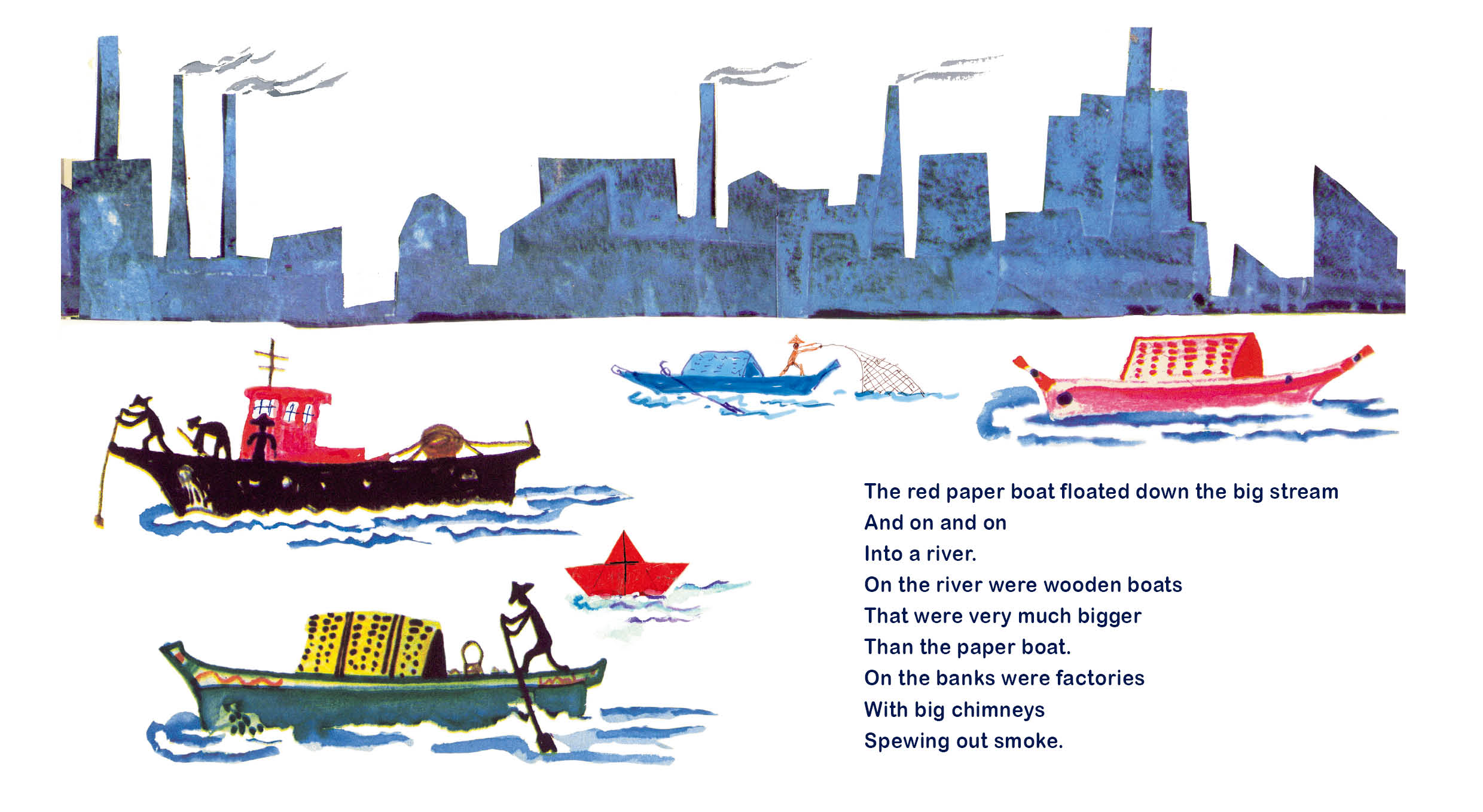

Egretllu: In 2015, I read Running Script by Liu Yun which included a story about Lake Bracciano in central Italy where the tide rose every night and flooded the lakeside villages, and the people in the villages turned on their TVs so that the eels could watch as well. The water flooded everything and the people disappeared but the rest of the world was still very normal. It was such an amazing image and I was desperate to draw it. That was really the background against which I wrote the first words of Somewhere.

My publisher and I revised both the text and the illustrations many times, and during our meetings I was particularly impressed by all the questions they asked about the characters’ backstories. For example, what did the diver do for work? Was he married? Did he have kids? Who were his family? What happened when the flood came? Was the diver religious? And so on and so forth.

While I was illustrating the book, I listened to Summer Lei’s song “The Day After Rain” over and over again. I told my wife and our children that the track was like the theme song for the book. When I had to review the manuscript, I had the song on in the background and could feel when the rhythm of the book was in sync with the music. I really loved doing that.

Locus Publishing saw the first draft back in July 2018, and we didn’t have the final version until over three years later in February 2022. I hope my future books won’t take quite so long [Egretllu laughs]. In terms of the challenge, I just hope that people like the book after they finish reading it. It’s a bit sad but it’s warm too, in the same way our lives are a mixture of happiness and sadness.

Wu Wen-Chun: You use a combination of warm-toned colors like yellow and cooler-toned colors like blue, and they interweave so if one spread is in yellow then the next will be in blue. The image composition matches the two tones throughout the book, so for the most part the yellow is only used for the dog, Toto, which portrays a warmth that reflects the character’s inner emotions; whereas the blue is used for a lot of buildings and street scenes when the diver is walking alone in the more realistic scenes, which convey a sense of alienation after being cut off from the outside world. The way the yellow and blue pages intertwine gave me such a strong sense of being in the wrong time and that things had shifted, while also giving the book its own unique narrative rhythm. What were the main things you considered when deciding on the image composition for the illustrations and what colors to use?

Egretllu: I wrote the book first, then did the illustrations. The words that readers see in the published edition are not the same words that I wrote down at the time. For example, there was this line that just appeared in my mind when the diver misses Toto: “I want to go for a walk with you, Toto.” I pictured the diver standing in the living room looking out the door where Toto no longer stood. However, this image never made it into the book and we placed the text on the previous page.

In other words, the internal and external worlds are expressed independently of one another. First, we read a page of text (the mind) which lets the reader see the protagonist’s inner thoughts, and then on the next page we see an image without text (the real world) so the reader understands what makes the protagonist think this way. This structure means that even though the storyline keeps moving forward, it’s actually a process of continuously rewinding and replaying the story from one paragraph to the next. And in terms of the image composition, I deliberately kept the pages of inner thoughts empty to give a sense of negative space, whereas the pages in the real world felt full which strengthened the impact that the two types of pages had on each other.

Wu Wen-Chun: For you, what are the essential elements that make some “somewhere” a “good place” (whether it be physically or psychologically)?

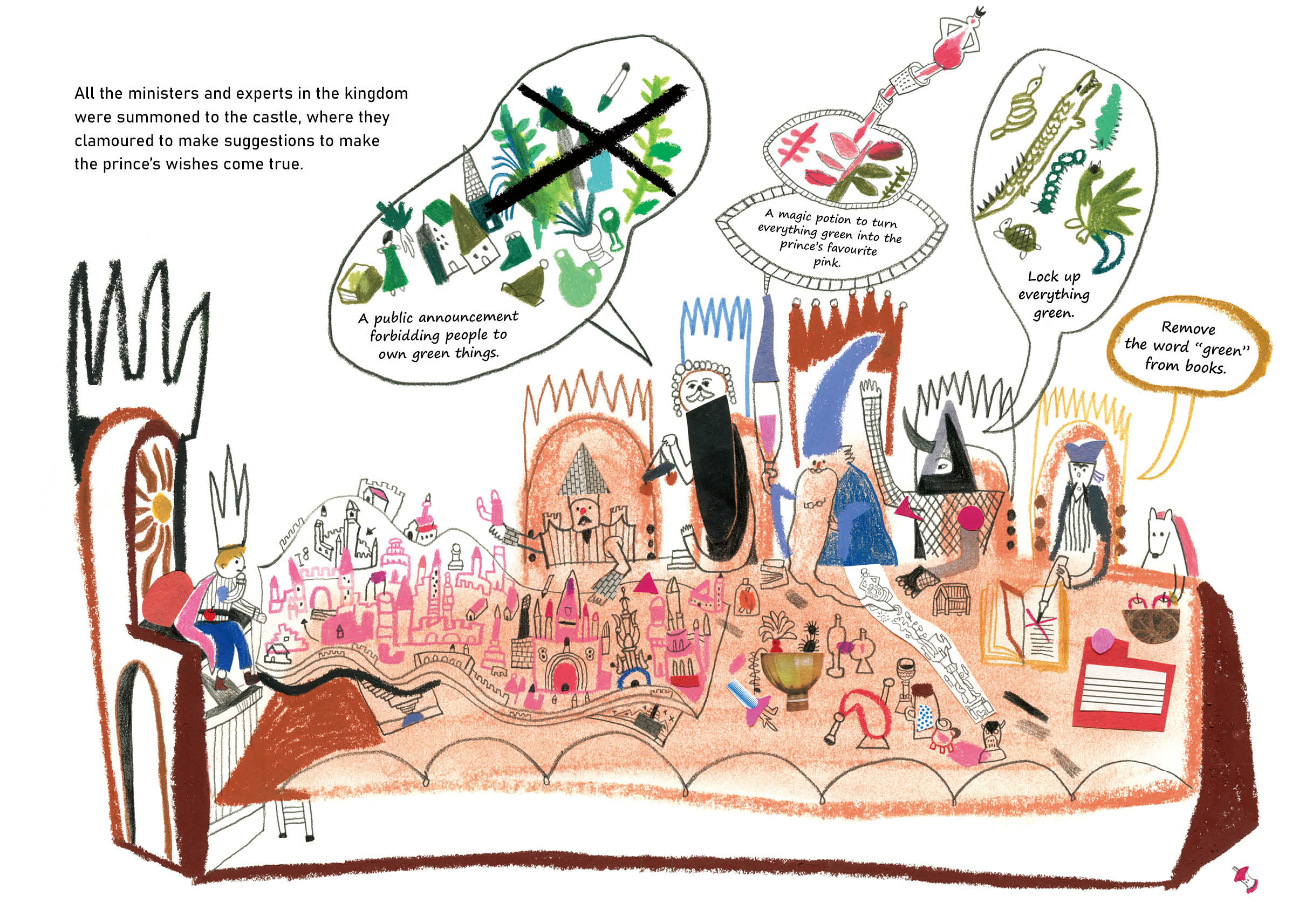

Egretllu: In the book, the places that the diver swims past used to be good places for humans but those spaces weren’t the same after the flood. Even though they had changed, they’d become happy places for the fish. So, I think for me, a “good place” is somewhere you can go to relax and feel content.