Over 30 years ago, almost all of Taiwan’s picture books were translations from English and Japanese. There were very few local artists involved in the creation of picture books at the time, and if you walked into a bookstore it would have been difficult find a picture book featuring Taiwanese children. Under these circumstances, the Hsin Yi Foundation, which promotes reading in early childhood, established the Hsin Yi Picture Book Award in 1987 to encourage local creativity.

In 1988, the inaugural award was won by Let’s Get Mung Beans, Momma! Today, it is a classic Taiwanese picture book, and the Hsin Yi Picture Book Award has become the country’s most important prize for original picture books. By the award’s 31st year, a total of 145 prizes have been awarded, 90 original works have been published, and more than 30 titles have been published in other languages.

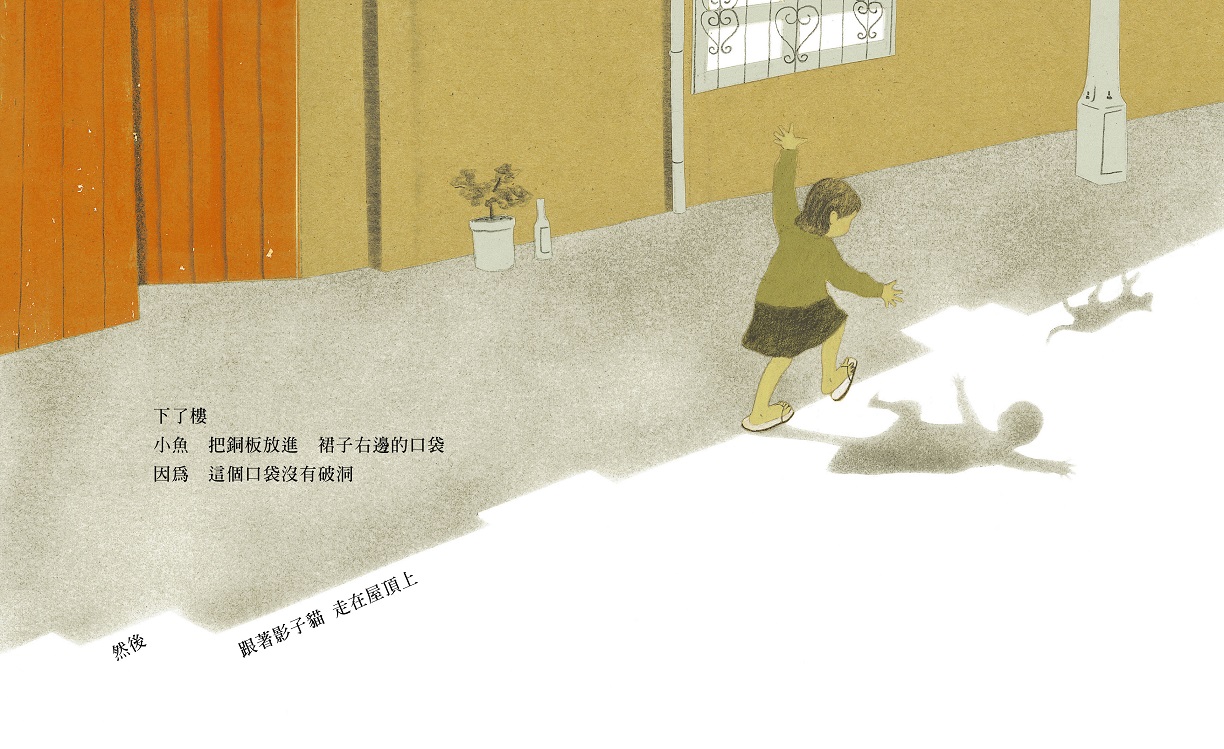

On My Way to Buy Eggs

They include the 13th prize-winner, On My Way to Buy Eggs, which was featured in Publishers Weekly’s Best Children’s Books of the Year. Guji Guji, which won the 15th prize, has been translated into 15 languages, it won the Peter Pan Award in Sweden and the English edition topped the New York Times bestseller list. Guji Guji tells the story of a crocodile who grows up with a family of ducks after his egg rolls into a duck nest. One day, three malicious crocodiles find him and try to convince him to eat some ducks with them. The story, which deals with issues such as adoption, love, and identity, has become popular in many countries. It is filled with many dramatic twists and turns, and has been adapted for the stage in Sweden, New Zealand and Spain.

.jpg)

Guji Guji

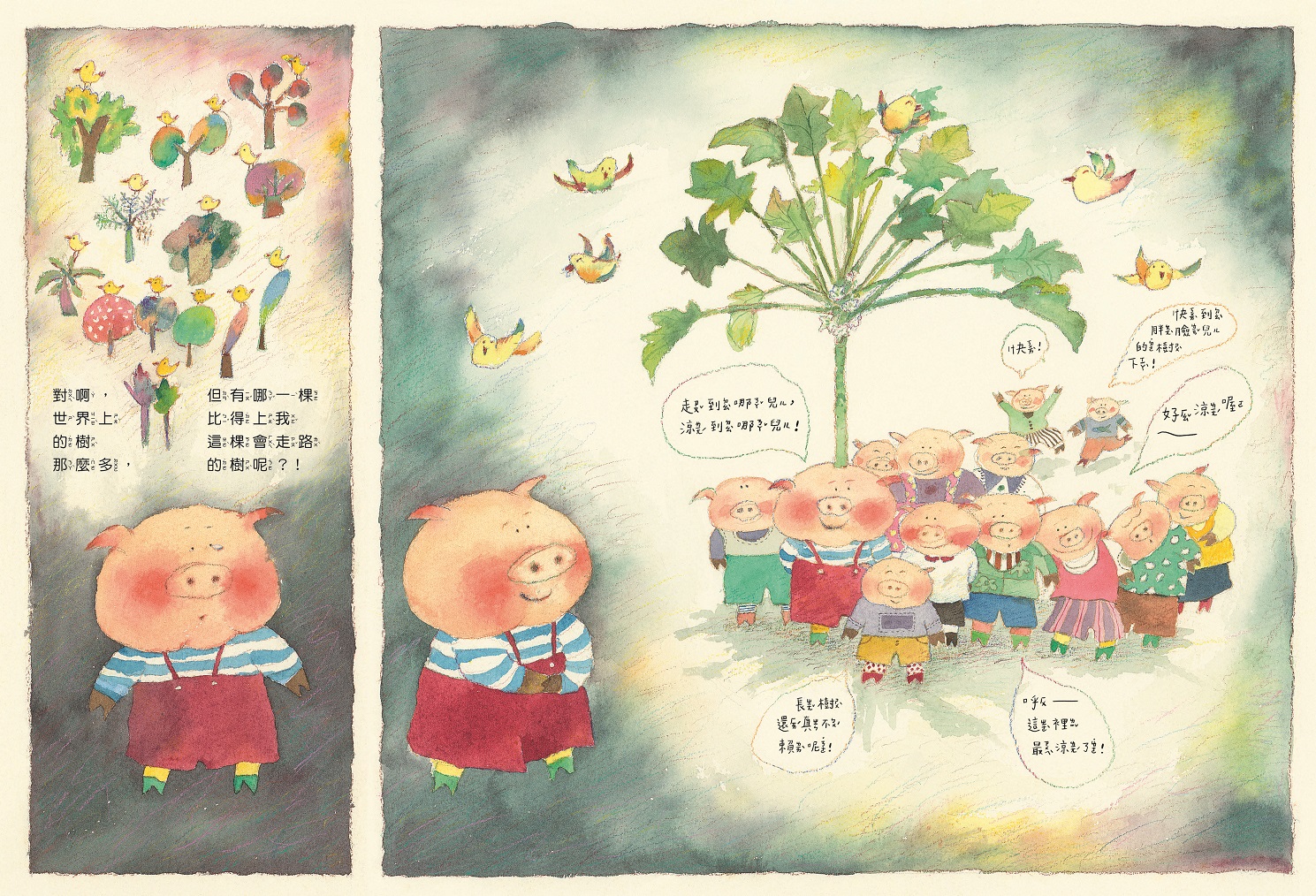

For over thirty years, the award-winning titles have covered a huge range of different childhood experiences. Let’s Get Mung Beans, Momma! includes the processes of growing mung beans, cooking mung bean soup and making mung bean popsicles, which are common childhood memories for Taiwanese people. The book has a succinct writing style, but alongside the meticulous illustrations, it captures the friendliness of the grocery store and everyday life as mother and child, adding plenty of details for children to look at. In the sixth prize-winner, Spit the Seeds, a piglet accidentally swallows papaya seeds and starts to worry that a tree will grow out of his head, but then he imagines small birds building nests in the tree and people cool-off in its shade, which shifts his mood and fills him with anticipation. This humorous way of thinking not only makes children laugh, but also conveys the most precious characteristic of childhood: the power of imagination.

Spit the Seeds

Similarly, many of the books explore the power of childhood imagination. In On My Way to Buy Eggs, a young girl looks at the world through a blue glass bead and imagines that she is a fish in the ocean, then later she has a make-believe game where she pretends to be her mother talking to a shopkeeper. As School Library Journal said, “This universal tribute to the power of a child’s imagination will strike a familiar chord with dreamers everywhere.” The 14th prize-winner, I Really Want to Eat a Durian, features a small mouse that has never eaten durian and really wants to know what it tastes like, so he goes around asking other animals about it, resulting in all the animals in the forest wanting to eat durian. The small mouse represents a child, and the string of words illustrated in the sky above him, “I want to eat durian”, reflect the unabashed innocence of children. The imaginative scenarios depicted in these books are all from the perspectives of young children and reflect the purpose of the Hsin Yi Picture Book Award. Interestingly, Thailand, which produces a lot of durian, was the first overseas country to publish I Really Want to Eat a Durian.

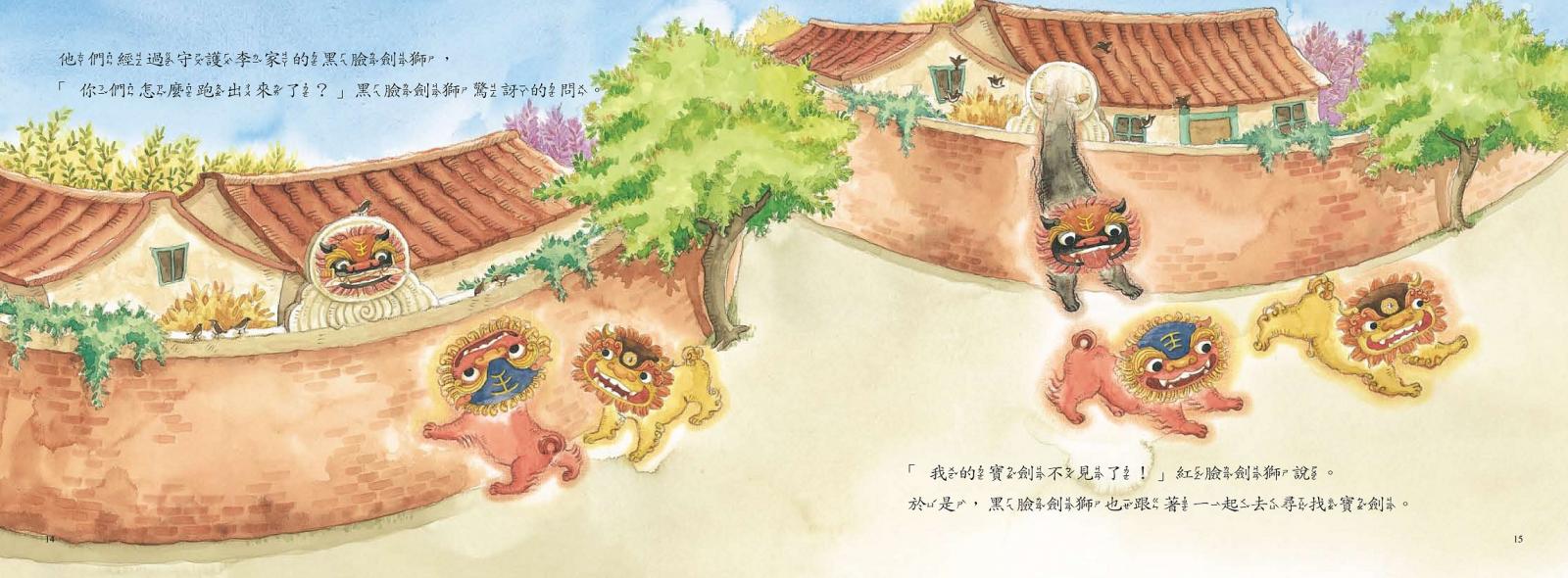

Some of the prize-winning works are demonstrations of local Taiwanese culture, such as the 27th winner, Little Peach, which tells the story of the Hakka rice cake; while in the winner of the 30th prize, A Busy New Year’s Eve, the adults are busily preparing for Chinese New Year, creating a fun atmosphere for children to learn about all kinds of New Year’s customs. The subject of the 20th winner, The Sword-Lion Who Lost His Sword, is a tradition from Tainan known as a sword-lion. With the blessing of his homeland, the sword-lion sets out to find the double-edged sword, but when it is nowhere to be found, the village residents ask the gods for a prophecy. The author incorporates folk beliefs into the highs and lows of the story, so that it is still enjoyable to read for children who aren’t familiar with the cultural background.

The Sword-Lion Who Lost His Sword

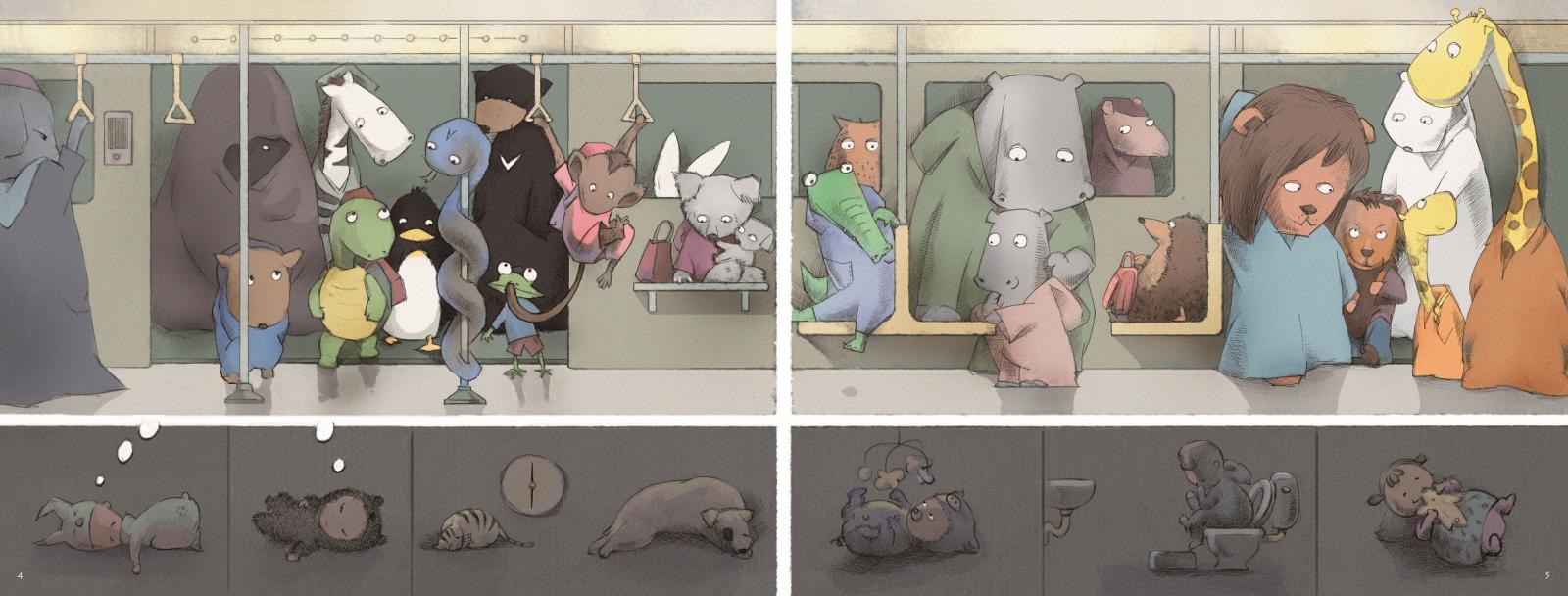

With time, we’ve also seen prize-winning works which have their fingers on the pulse of modern society. When stray dogs became a cause for concern in Taiwan, the 10th prize-winner, The Stray Dogs Around My House and I, featured a protagonist who took a different route to school to avoid stray dogs. The winner of the 20th prize, A Trip from the Zoo, has the animals tour Taipei by riding the subway; while in the 21st prize-winner, One Afternoon, the protagonist shows the reader around Taipei by bicycle; and Papa’s Red Umbrella, which also won the 21st prize, depicts sky lanterns in Pingxi. These works all portray a popular way of life in Taiwan today.

A Trip from the Zoo

Many of the winners have said that they started creating to participate in the prize, or that they compete in the prize every year. The award’s most significant achievement is that it has encouraged more people to create for children and supported many important creators of picture books, such as Chunlun Lee, Bei Lynn, Chen Chih-Yuan and Liu Hsu-Kung etc.

The Hsin Yi Picture Book Award has captured Taiwan’s landscape and culture, through words and illustrations in the form of picture books. These books not only give children a local culture they can identify with, but let children across the world enjoy their charming stories.