For the past few months, Taiwan’s domestic news cycle has been dominated by the upcoming January 2024 presidential election: a billionaire businessowner entered the race and (after failing to gain traction) dropped out; two of the opposition parties joined forces and (after confirming their incompatibility) broke up. But the campaign was far from the only story. This year has been marked by the delayed arrival of a #MeToo movement that is yet to fully settle, and the sudden and widespread adoption of AI-based writing tools has stimulated national debate and conversation on issues of plagiarism, authorship, the future of professional environments, and the need to reassess educational approaches.

Thinking more globally, we in Taiwan have watched with horror the emergence of two major wars in two years. Of course, international onlookers inevitably ask: “Will Taiwan be next?” And, while it would be an over-simplification to say that those of us on these islands do not feel a measure of unease, the threat of invasion has existed for decades, and Taiwanese lives are for the most part not as affected as those outside might think.

Cross-strait relations and associated tensions have, however, been felt in other ways, particularly in the increasing numbers of Hong Kong migrants settling in Taiwan, with yearly arrivals doubling over the past twenty-four months to over ten thousand people per year, amongst whom are new and welcome additions to our industry, most notably the 2046 imprint and the Causeway Bay Books bookstore.

Tang Siu Wa (middle), at the Taipei International Book Exhibition, 2023, launching the 2046 imprint.

Image source: https://p-articles.com/heteroglossia/3597.html

For many working in publishing, one of the most affecting pieces of news this year was Fucha’s arrest. Fucha, who moved to Taiwan over a decade ago, is a highly respected and influential figure, known for publishing critical deconstructions of the cultural and social ideals surrounding contemporary China; he was detained after returning to Shanghai for a family visit this past spring and has not yet returned.

In February this year, the Taipei International Book Exhibition (TIBE) resumed its regular annual schedule; the number of attendees exceeded 500,000 people, a doubling from the previous year and a figure which represents 87% of 2019’s pre-pandemic high. Over the past few years, there has been a steady rise in the popularity of author events at the fair, and 2023 saw TIBE hosting over 800 events, attended by over 470 publishing houses from 33 countries. In this way, Taipei might well be considered a hybrid fair, catering to both professionals and the general public alike, and, with the sheer number of events, it’s starting to resemble a literary festival.

View of the floor at the Taipei International Book Exhibition, 2023.

Image source: https://www.rti.org.tw/news/view/id/2158128

Transforming the fair such that it caters to all needs should indeed be praised, but some argue that the organisers have not yet clearly defined its purpose; this lack of clarity, they claim, undermines the many excellent events. (Noise interference — due to closely spaced, concurrent talks — and ticket prices that do not reflect the increased number of high-quality events are two commonly cited complaints.)

More broadly, the industry continues to tackle the worrying trend of year-on-year devaluation. In 2022, total revenue was estimated at around USD 575-600 million; this, combined with inflation, which has affected the price of paper, logistics, labour, and other areas of production, means margins are smaller than ever. Taiwan, like many countries in East Asia, does not operate a hardback-first-paperback-later print cycle (through which publishers might recuperate initial production costs). Historically, sales volumes were enough to make margins work with paperbacks alone, but that business model has struggled to adapt to modern consumer habits, where volumes have decreased and preferences are more widely spread.

Looking at the Taiwan Cultural Content Industry Research Report, which was commissioned by the Taiwan Creative Content Agency (TAICCA) and compiled with data from 2021, over 82% of publishers (including general, professional, and textbook publishers, but excluding those publishing comics and magazines) are based in the Greater Taipei metropolitan area. Over 75% of publishing houses are small and medium-sized enterprises, and just over 5% are large-scale publishing groups (with capitalisations in excess of USD 3.2 million). The rising cost of running a business in our nation’s capital, shrinking domestic sales, and a lack of investment by which to plan and execute digital transformations are just some of the key issues to address.

In numbers taken from the same report, 96% of the industry’s revenue comes from domestic sales, including those of books, audiobooks, multimedia licensing, and ebooks. (Note that overseas ebook sales cannot easily be separated from those within Taiwan.) Foreign rights sales make up less than 4% of total revenue and are heavily reliant on Sinosphere markets, such as China, Hong Kong, and Macau, which together comprise nearly 80% of all rights sales. (Of the remaining portion, South Korea accounts for around 5%.)

Whilst both the comic and magazine sectors likewise rely heavily on Taiwan’s domestic market, which supplies over 90% of total revenue, there are nevertheless some interesting deviations from the industry at large.

97% of all comics published in Taiwan are acquired through foreign rights (mostly from Japan), and only 3% are titles produced by local creators. The few local offerings, however, punch above their weight in terms of international rights sales, 55% of which are to Japan, 21% to France, 9% to China, and 4.5% to South Korea. This distribution pattern, so unlike that of the Sino-centric foreign rights sales for books, might well be attributed to the medium’s illustrated nature, which could allow for broader international appeal. (And, crucially, Japan and France are two of the world’s major markets for comics.) Moreover, there has been a boom in Western interest in East Asian pop- and sub-cultures, driven primarily by Manga and K-pop, and Taiwanese content might therefore be looked upon with renewed interest.

Alongside the TAICCA report, it is useful to review the annual National Central Library Reading Report to gain further insight into Taiwanese reading habits. The latest edition, which uses statistics from 2022, shows that readers have returned to the library, with visitor numbers up 47% compared with 2021. Over 93 million books were on loan in 2022, with the most popular categories being literature, applied science, natural science, and social science, and the biggest borrowers being the 35-44 age group. An average of 4.5 books per capita were borrowed from libraries across the country; the top title was self-help bestseller Atomic Habits, by James Clear, followed by multiple self-help books from domestic authors. This matches the bestseller trends as per Eslite’s and Books.com’s annual end-of-year analyses.

Entrance to Taiwan’s National Central Library.

Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Central_Library

Another area of growth was ebooks on loan, which increased by 257% compared with 2020. And, during the pandemic, we finally saw a significant upward shift in the sale of ebooks (as well as the attendant increase in the number of titles published), whilst the average retail prices of ebooks have risen by over 33% in the past two years.

Although it is true that business for publishers in Taiwan might be challenging, given the available statistics, I question the oft-repeated statement that people “don’t read anymore.” It is clear that the public does enjoy reading — their engagement just isn’t being effectively translated into revenue. So, what can be done to overcome these challenges?

Public lending rights is a policy — already implemented in many countries — that compensates publishers and authors for potential losses of sales to public library lending. The first Taiwanese trial, however, wasn’t judged a success, due in part to the pilot’s limited scale and various bureaucratic complications. Nevertheless, public hearings were held to improve the process, and discussions are underway to renew the trial.

As e-commerce retail platforms continue to promote books with ever-increasing discounts, many publishers have begun calling for the implementation of a fixed-price policy; there are also, however, oppositional voices — mostly free-market advocates — who stand by the principle of economic self-regulation, and it must be said that, against rising discounts, average retail prices have increased.

These policy ideas and others in development have been shaped by repeated exchanges with experienced professionals, whose insights are already helping publishers cultivate large and diverse readerships and teaching them (whether they be independent or commercial) to create marketing strategies catering to divergent readerships and fast-changing consumer habits. So, while we navigate this long and sometimes painful transition, it is worth remembering that progress has been made and fresh developments are gaining momentum.

2023 has been an eventful year for international promotion. For many, it was the first real post-pandemic year, especially when it came to overseas author engagements. On top of its regular annual attendance at global book fairs, such as Angouleme, Bologna, Seoul, Frankfurt, Shanghai, and Guadalajara, Taiwan was selected as guest country of honour for Switzerland’s Festival de bande dessinée Lausanne (BDFIL), where six graphic novelists, among them Sean Chung (小莊), author of 80’s Diary in Taiwan, and Zhou JianXin (周見信), author of The Boy from Clearwater, and three film directors were invited to participate in roundtable discussions and other events. The two above-mentioned authors have each sold foreign rights in numerous territories, including France, Italy, and Germany, and being selected as the guest of honour nation surely speaks to the rising profile of Taiwan’s cultural output.

Inside pages of The Boy from Clearwater displayed at BDFIL.

Image source: Centre Culturel de Taïwan à Paris

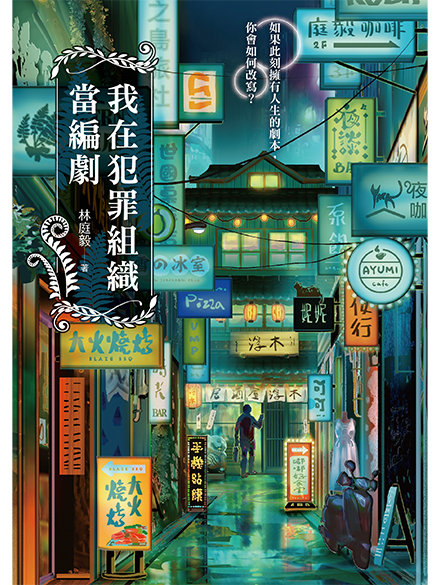

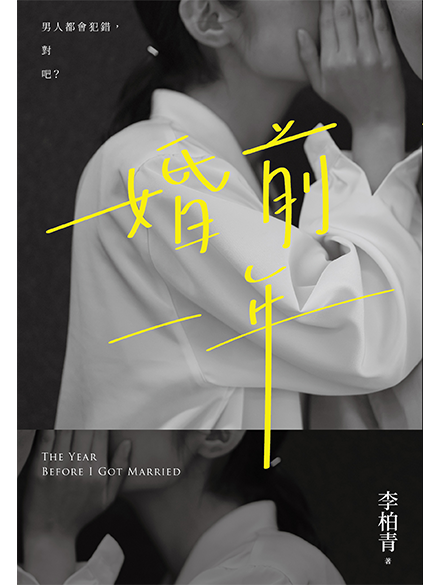

Award-winning novelists Li Kotomi (李琴峰) and Kevin Chen (陳思宏) were both writers in residence at Iowa’s prestigious International Writing Program; while there, Kevin Chen attended the Toronto International Festival of Authors with children’s author and illustrator Bei Lynn (林小杯). Yang Shuang-Zi (楊双子), who writes queer stories set in the Japanese colonial period, visited Japan in late spring to promote the translated edition of Taiwan Travelogue, which was reprinted just seven weeks after its initial release. Pioneering feminist writer Li Ang (李昂) travelled this autumn to France for the launch of her novel Le Banquet aphrodisiaqu.

Interview with Yang Shuan-Zi, published in Japan’s leading newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun.

Image source: https://www.openbook.org.tw/article/p-67743

Historically, for Taiwan-based agents, selling rights into the English-language world has been challenging. When looking over the 2024-2025 list, however, one gets the distinct sense there is increasing attention being focused on Taiwan literature. We can expect to see English translations of Still Life in White, Lai Hsiang-Yin’s (賴香吟) award-winning novel set during the authoritarian White Terror period; the final volume of the critically praised graphic novel, The Boy from Clearwater; The Eyes of the Sky and Mata nu Wawa, two backlist classics from acclaimed Indigenous Tao writer Syaman Ranpongan (夏曼.藍波安); two of Yang Shuang-Zi’s novels; and poetry from both Ling Yu (零雨) and Cikada Prize winner Chen Yuhong (陳育虹).

One highlight from outside the Anglosphere is the crime novel Before We Were Monsters, by Katniss Hsiao (蕭瑋萱), which has sold rights in six countries and secured a film adaptation. Port of Lies, by Freddy Fu-Jui Tang (唐福睿) — already adapted into a Netflix-drama series here in Taiwan — addresses complex social issues, such as the death penalty, racial identity, and the exploitation of migrant workers; it has sold rights in three languages. Successful sales into the Spanish language world have primarily involved illustrated titles, and we look forward to the publications of Where Would I Be Tomorrow?, by author and illustrator Jimmy Liao (幾米); Practicing Goodbye, Bei Lynn's moving graphic novella about a missing beloved dog; the Bologna BRAW Amazing Bookshelf selected picture book Still Young Still New, by Higo Wu (海狗房東) and Chen Pei-Hsiu (陳沛珛); and The Fox and the Tree, a picture book by Chen Yan-Ling (陳彥伶).

Finally, if we return to ways that we might transform our industry, it is evident that investment in domestic talent is a driver of enduring change; it must, therefore, be financially viable for gifted young people to embark upon a writing career. And, in a small place like Taiwan, where access to the global market is key to the ongoing development of our industry, English sample translations are invaluable resources when promoting Taiwanese content abroad.

So, it was with great pleasure that many of us reacted to the recent decision, taken by the Ministry of Culture, to double the number of annually produced English translation samples (titles to be selected by panel judges led by the team at Books from Taiwan). More samples means more publicity and success in foreign sales; this generates important positive feedback, which in turn drives sales in our domestic market, sparking further worldwide interest.

As our authors are gaining popularity, both at home and internationally, and as the Eslite and Books.com bestseller charts list more local authors than ever, well-endowed literary prizes provide recognition and reward for established and emerging authors alike. Major prizes, such as the Golden Tripod, OpenBook, the Taipei International Book Exhibition Prize, and the Taiwan Literature Awards, draw great attention and increase sales of both winning and shortlisted books. And the Lin Rung San Prize (林榮三文學獎), the Indigenous Peoples’ Literature Award (原住民文學獎), and the Taiwan Literature Award for Migrants (移民工文學獎) give top prizes to unpublished authors that range from USD 3,000-19,000. It is this second category that is especially important to underprivileged and emerging writers, who might use the prize money to kick-start their dreams or capitalize on the increased publicity to find publishers and secure arts grants with which to complete their projects.

The 2023 Taiwan Literature Award for Migrants award ceremony.

Image source: https://www.mirrormedia.mg/story/20230312soc014

And even if some publications target a niche audience and have little commercial potential, it seems obvious to me that it is exactly this type of literature that, over the past two decades, has inspired many authors of a “mainstream” tilt to include more challenging topics in their own writing, which has in turn diversified the public’s reading habits and appetites. Gender expression, LGBTQIA+ identities, folk tales, Indigenous civilizations, environmental issues, social justice, and many other pieces of our world are present on pages in ways like never before; there is always more to be done, but the creation of a vibrant environment for writers and readers is an inspirational work in progress.

Still, transition is not easy, and it might not be healthy to dream big without first grasping the practical realities of our industry. That is why understanding the macroeconomic facts, using data such as those collected by TAICCA and the National Central Library, is so important, just as is collaboration — both internal and international — by which we can improve our offerings for a changing and widening readership.

Earlier this month, some of my colleagues attended the Guadalajara Book Fair in Mexico, where, aside from exhibiting books, concerted efforts were made to reach local media outlets, universities, and chain bookstores in the service of developing stronger collaborative ties. This October, at the Frankfurt fair, Books from Taiwan celebrated its tenth anniversary with an event that was attended by over 100 professionals from around the world. Cultural transformations and investments take time, but these initiatives are just two examples of the type of cooperation that could encourage our industry to move together into a new future.

The Taiwan Pavilion at the 2023 Guadalajara Book Fair.

Image source: https://reading.udn.com/read/story/7046/7604408

Next February, we look forward to the 2024 Taipei International Book Exhibition, at which we will host the Netherlands as our guest nation of honour. And TAICCA will be relaunching its international fellowship program at the same time, inviting 30 professionals from around the world to join us in Taipei to gain insight on our publishing industry, meet authors, publishers, and readers, and (of course) enjoy some of our city’s many beautiful sights.

And with that, I’ll end this article; I wish you all a happy holiday season, and I hope to see you in Taipei soon.