Read Previous Part: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/latest_info.php?id=172

3. The Endless Possibilities of Comics

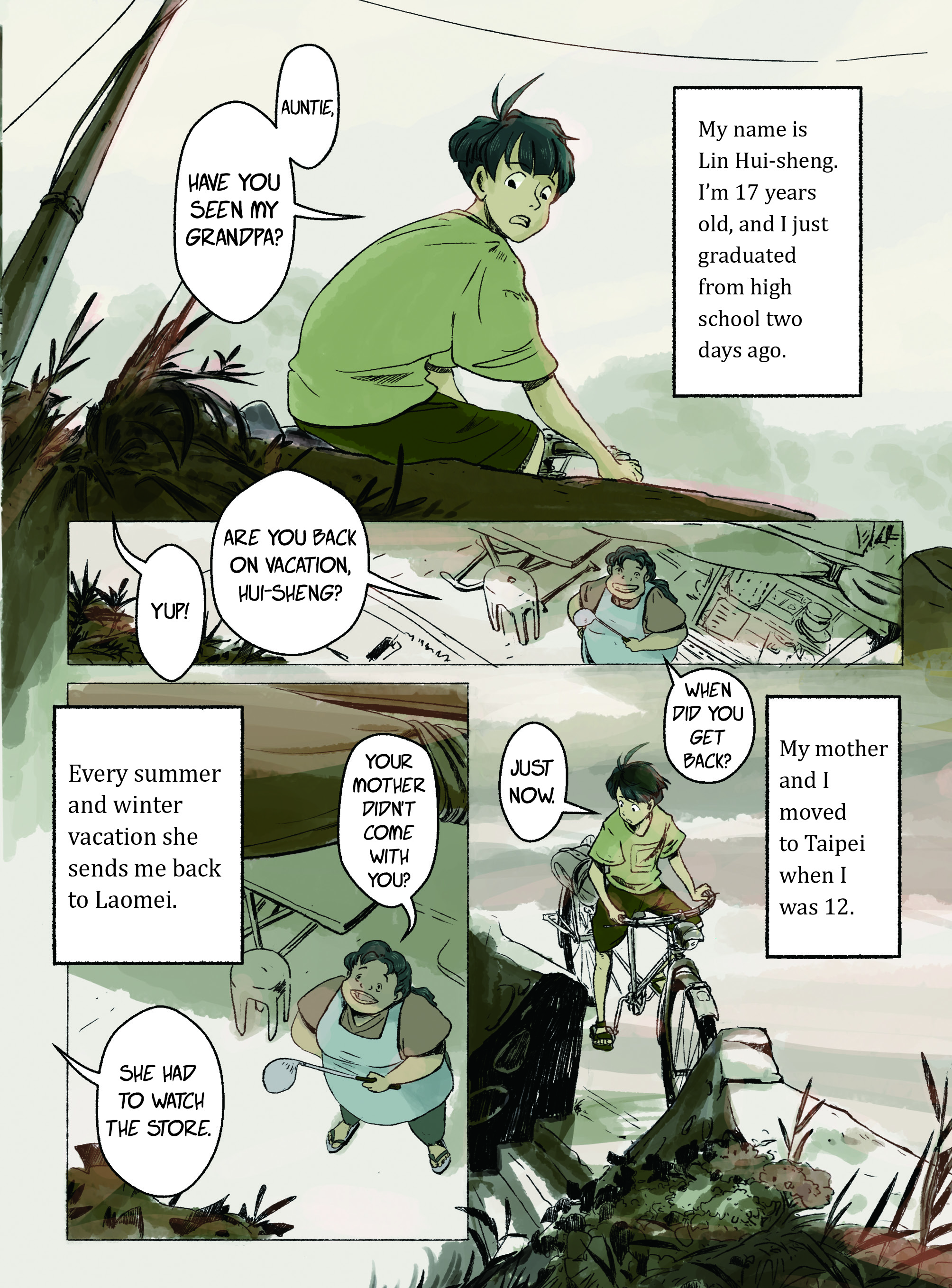

This year’s shortlist revealed once again just how unlimited the possibilities are for comics. New opportunities are brought about by changes in the media landscape, for example San Ri Juan Zi’s self-published comic Hi, Grandpa! Being Together and Then Saying Goodbye has a lot of traits that are common in today’s web comics, such as the way it uses sincere feelings that are true to life, like those stories you read on the internet that suddenly leave you teary-eyed and heartbroken. This multimedia approach is also reflected in the nominees for Best Cross-media Application: Tong Li Publishing Co’s work on The Monster of Memory: Destiny; and Secret Whispers which was a joint venture between Chimney Animation and Fish Wang, an illustrator, animator and director who won Best Animated Short Film at the 2019 Golden Horse Awards for Gold Fish.

The Monster of Memory was originally a comic by author-illustrator Mae and featured an ingeniously designed setting as well as a truly mind-blowing plot that was filled with metaphors of real-world relationships. It’s the sort of story that is perfectly suited to being adapted into a game as a more immersive way for readers to experience the world of the book. Fish Wang meanwhile, is known as a great all-rounder in Taiwanese comics and Secret Whispers can be seen as an “original multimedia work” because from the outset he uses different types of media to portray the teenagers’ “secrets” through different perspectives as the tension rises between them. In the future, the work might be seen as an important reference point in the development of Taiwanese comics, not just because it was set up as a cross-media project from the beginning but also because of the way it was a joint creative venture in the studio.

In addition to the possibilities brought about by other media, a lot of graphic novels have emerged among Taiwanese comics in recent years. The term “graphic novel” has been adopted from the West and encompasses works that are deeply experimental and avant-garde. A lot of readers who have been familiar with Japanese manga from a young age can’t help but flip through graphic novels and wonder uncertainly “Is this book really a comic?” This completely new experience and the excitement it provokes are precisely what makes graphic novels so fascinating.

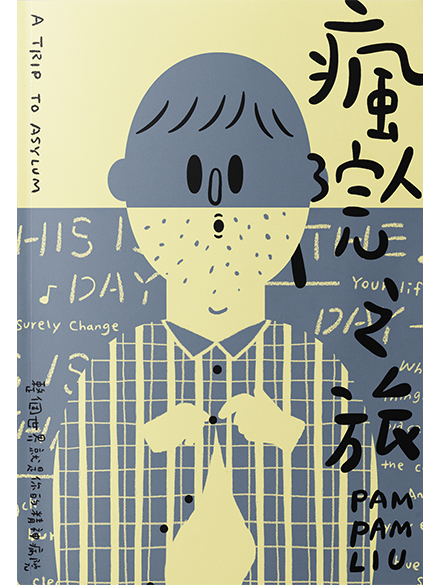

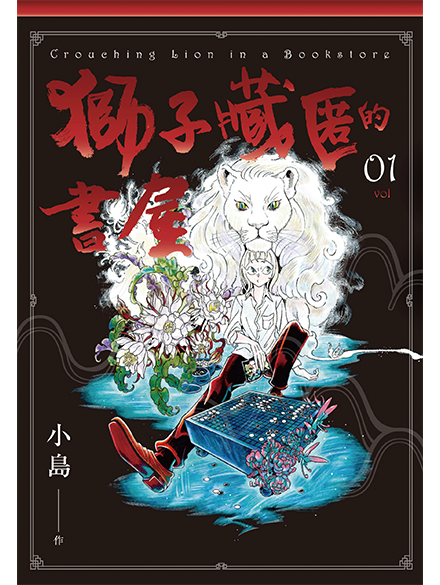

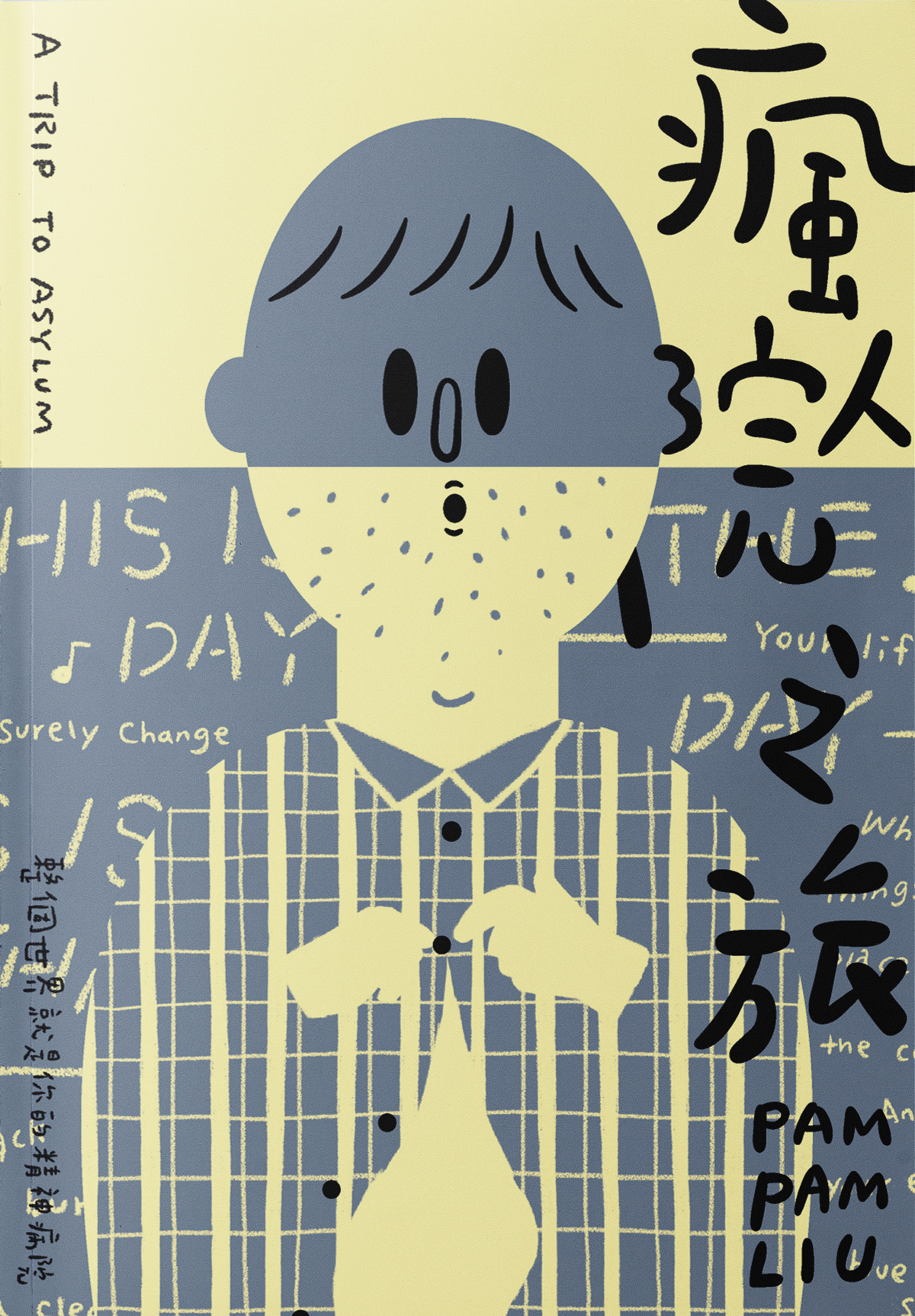

A Trip to the Asylum by Pam Pam Liu was the most provocative, nerve-wracking book of the year. A fictional story about mental illness and a psychiatric hospital, the comic is an all-out sprint that thrusts you straight into the darkness of the subconscious where you have no defences and there are no taboos. Reading it is like being in a comic book version of a Lou Reed song.

A Trip to the Asylum by Pam Pam Liu

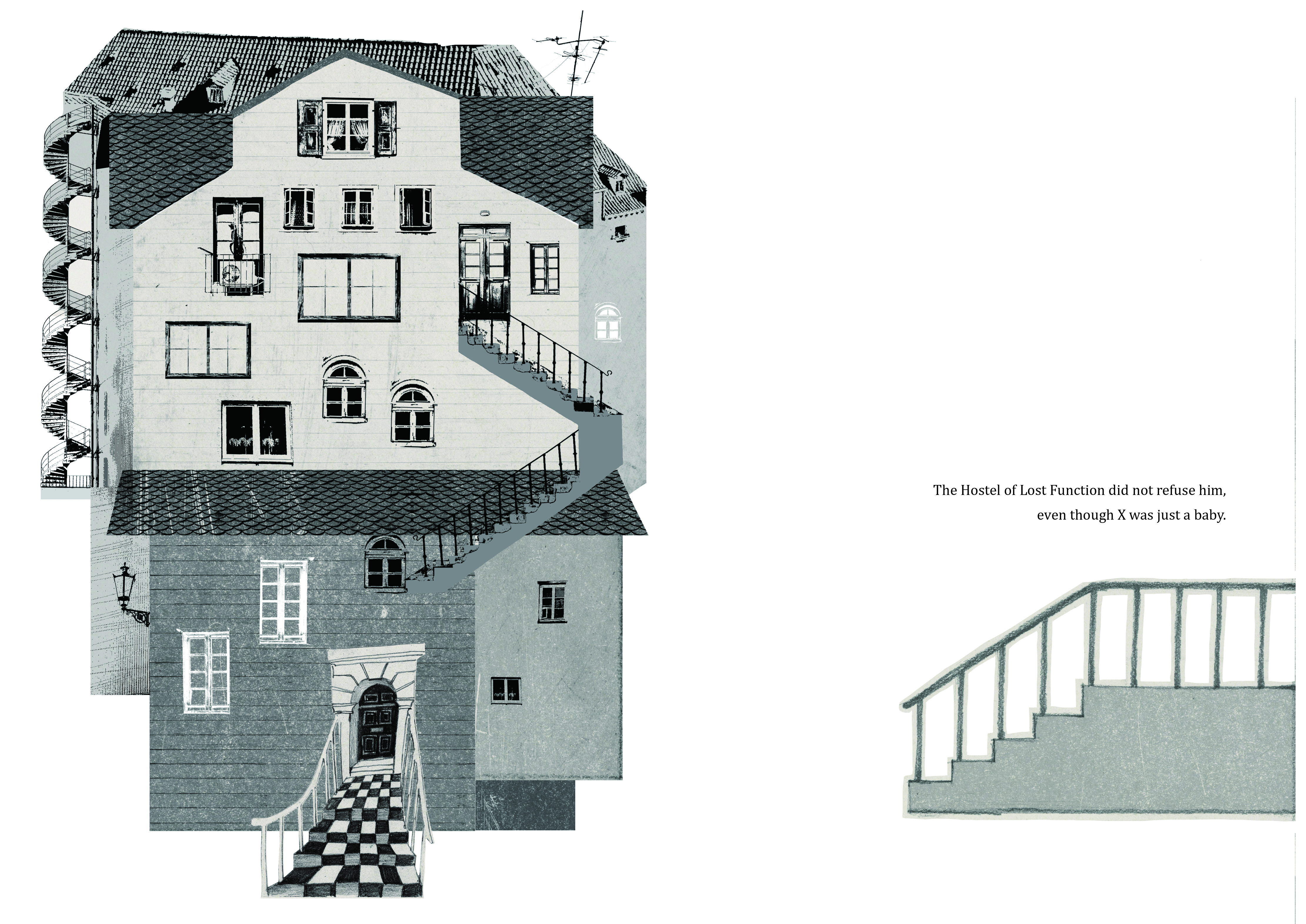

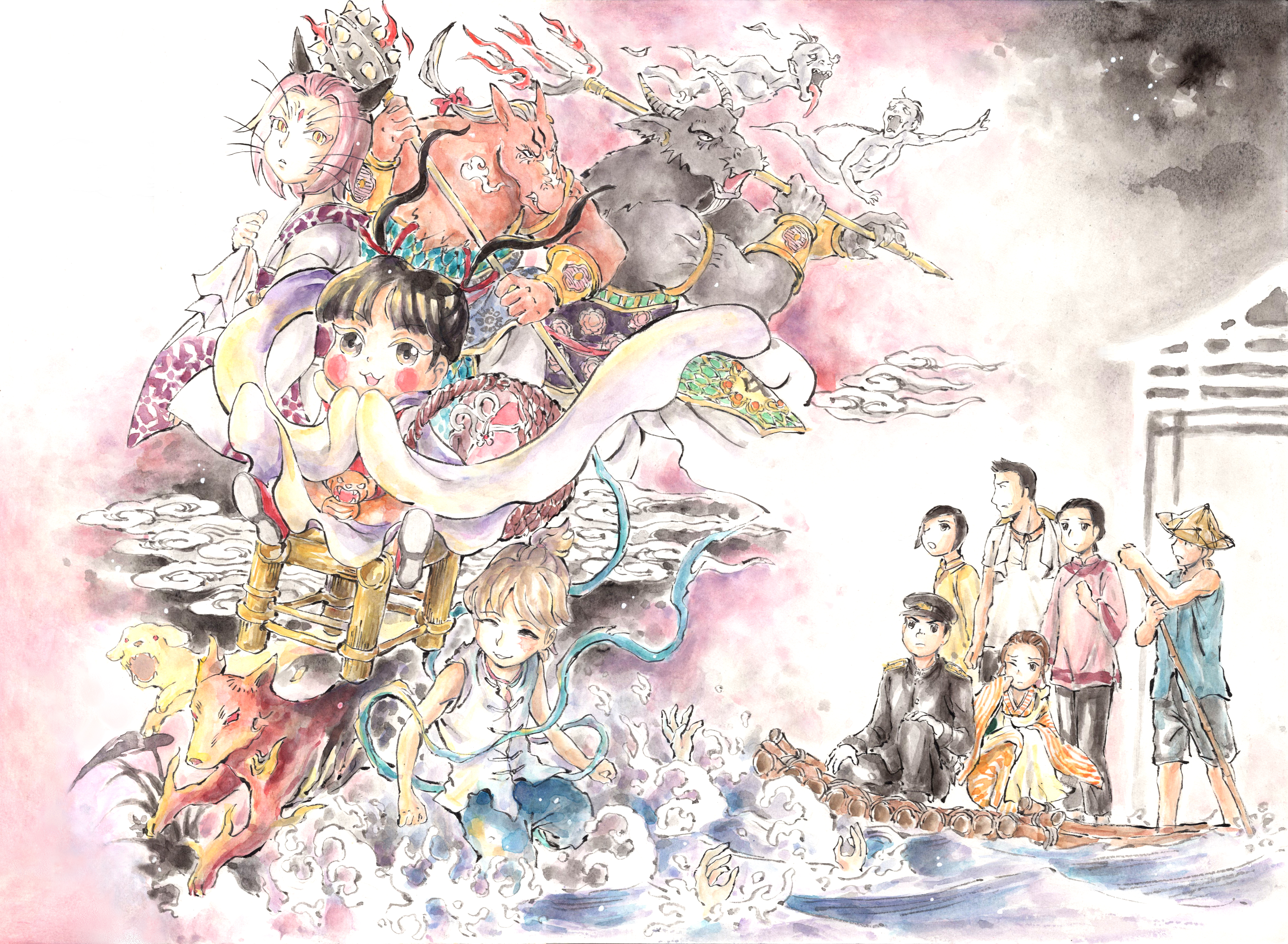

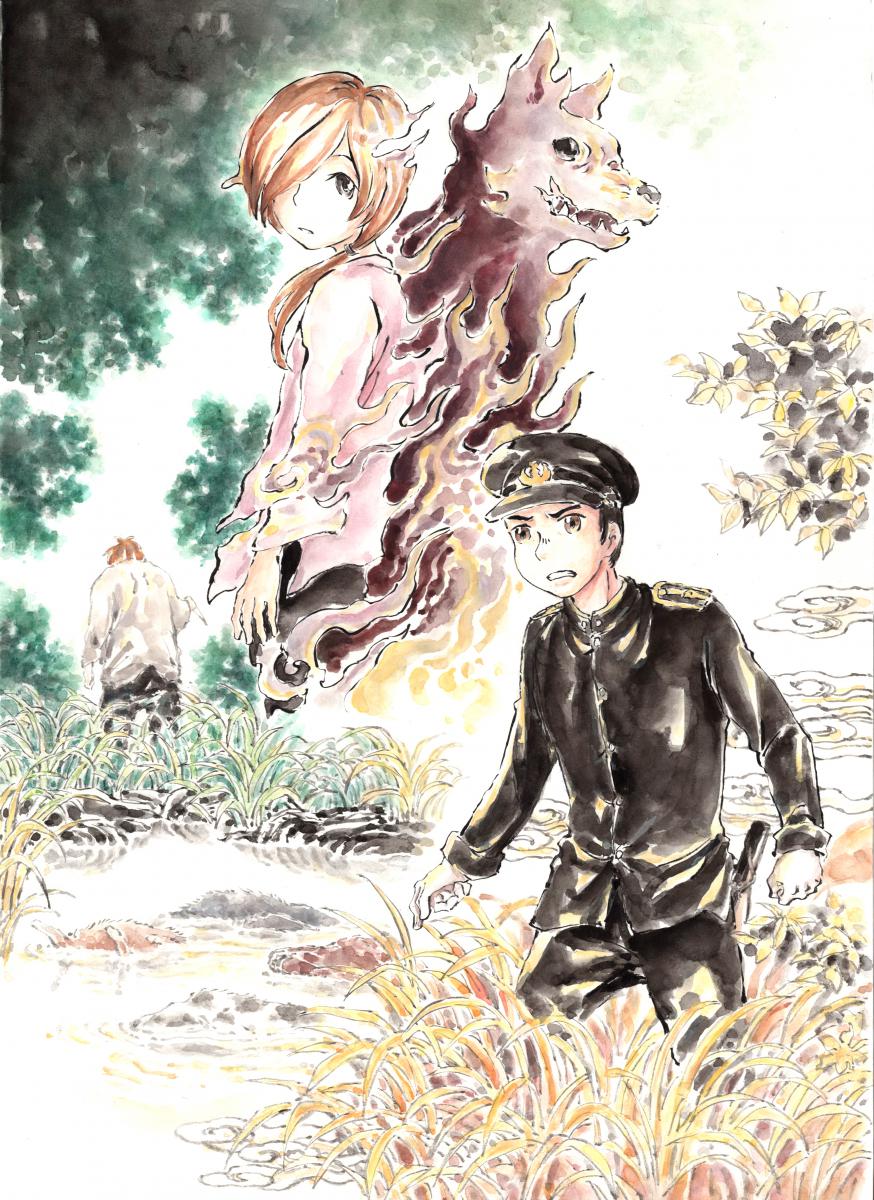

It is hard to think of a comic more different from A Trip to the Asylum than the nonfiction series Son of Formosa. The series is based on the life of Tsai Kun-lin, a political victim of the White Terror who published comics despite the authoritarian environment in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987. He won the Special Contribution Award at the 2018 Golden Comic Awards for his courage and perseverance in fostering the development of Taiwan’s publishing sector. For the Son of Formosa series, author Yu Peiyun conducted extensive research when writing the text and illustrator Zhou Jianxin used a range of visual methods to convey the myriad of twists and turns that Tsai Kun-lin experienced over the course of his life. It doesn’t just relay the facts but the images invite the reader to extend their imagination and in doing so the comic conveys a level of empathy that goes beyond the words of the text. Son of Formosa is a graphic novel that can be cherished as a classic both in Taiwan and internationally.

Son of Formosa by Yu Peiyun and Zhou Jianxin

In this new era of comics, even the older forms of comics that followed a reliable, clear-cut path are no longer restrained by the same rigid set of standards as they once were. In addition to graphic novels, works like Illustrated Taiwan Keywords: A Hand-Drawn History of 1940-2020 by Chiou Hsien-Hsin which look like picture books or nonfiction books centred around infographics will also have an impact on what are stereotypically considered to be “comics” in the future. There is an almost unlimited number of paths an image can take, so rather than holding onto outdated beliefs of what a comic should be, both comic creators and readers alike should adopt a more open-minded approach and embrace the endless possibilities comics have to offer.

Summary

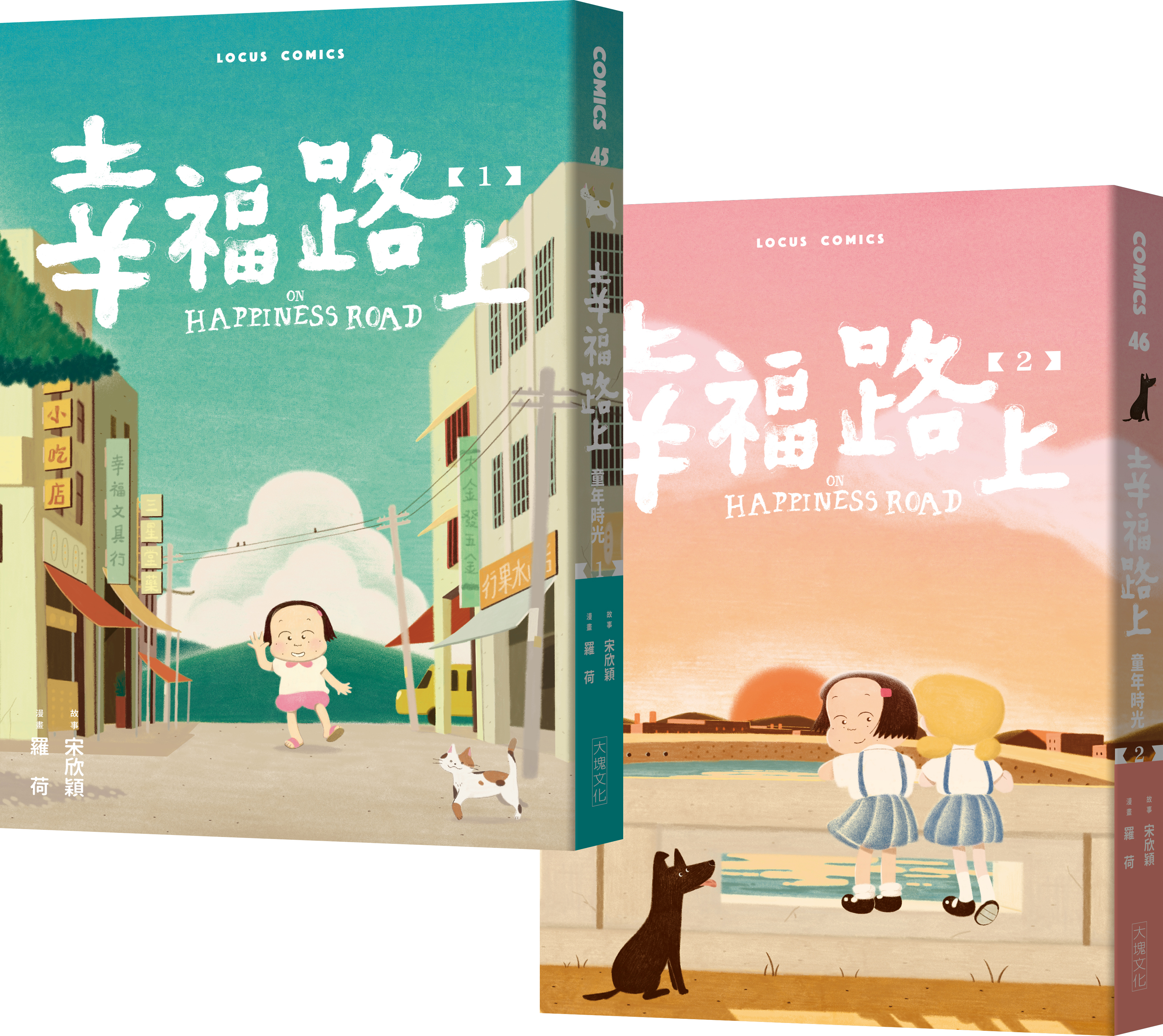

These three points are just my suggested highlights for anyone looking at the online exhibition of this year’s Golden Comic Awards. As with any exhibition, each visitor should use their personal interests and preferences to unearth their own understanding and appreciation of the exhibits. It is also important to acknowledge the work done by editors to help bring these visual adaptations of literature and history to life. Lin Yi-Chun (Managing Editor at Locus Publishing Company) won this year’s Best Editor Award for her work on The Ren Zheng-hua Collection: Drawn to Life + The Human Bun and on Secret Whispers; while the shortlisted editors included Huang Pei-Shan and Ho Szu-Ying (Editor-in-Chief and Editor at Slowork Publishing respectively) for their work on Son of Formosa, and Tan Shun-Hsin (Editor) for her work on Fantastic Tales of Splendid Blossoms. These exhibits are all undoubtedly great works of art which deserve to be poured over by visitors. However, there are physical limitations with all exhibitions and this was no exception. With a total of 226 works registered this year it was inevitable that some talent would go unrecognised, so this exhibition should only be seen as a starting point and readers should take their initial interest a step further because there are just too many beautiful Taiwanese comics out there waiting to be read.

Comics are a medium where stories are told through images and by using different themes or illustration styles what you are ultimately trying to achieve is a great story. Over the last few years, Taiwanese comics have produced countless great stories regardless of whether they are shortlisted for the Golden Comic Awards or not. These are stories that will make you laugh, make you cry, and at some point they might even accidentally become something that saves your life, and this, more than anything, is what I want you to know about the Golden Comic Awards and the corresponding exhibition, not just this year but in all the years to come.

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)