I arrived in Taiwan late on a Sunday afternoon in November. Outside the air-conditioned halls of Taoyuan International Airport, the weather was humid. In London it had been raining on and off for weeks. I had been travelling for sixteen hours and back home it was still early morning. As the taxi sped from the airport along the freeway towards the hotel where I and the other fellows of the Taipei Rights Workshop would be staying for the week, the city grew in density around me until at last the world’s second tallest building, Taipei 101, came into view, framed by the mountains. Knowing very little about Taipei, I had anticipated tall glass skyscrapers, buildings jutting against one another. I had thought it would feel like a city from the future: uniform, glassy, unwelcoming. What I saw from the taxi cab window was far more familiar: a jumble of architectural styles, bulky steel and glass buildings rubbing shoulders with older blocks, wide plazas bordered by a rare glimpse of a Japanese factory or Confucian temple; a colour palette with more earthy tones than silvers. All the while in the background was the presence of the mountains. Taipei felt cradled. By the time the taxi arrived at our hotel, I was in love.

The Taipei Rights Workshop has been bringing together publishing professionals from around the world with Taiwanese editors, translators, and rights sellers since 2013. In the 2016 cohort, we were eight – six editors, a translator and a scout – from three different continents; seven different countries; and six different time zones. All of those present were facing challenges in their markets – diminishing review space, bookshops and readers that are shy of translations, the proliferation of other endless forms of entertainment. Publishing, it is often said, is in a state of crisis, but here we were, eight people who had travelled a great distance in the hope of making new connections and bringing home a piece of Taiwanese literature. The fellowship itself, founded and run by the indefatigable agent Gray Tan and his colleagues at the Grayhawk agency, is an example of this same optimistic spirit and a resolve to make literature travel.

Over the next five days, Gray and our hosts Grace Chang, Jade Fu and Emily Chuang acquainted us with the history and culture of Taiwan. At the National Palace Museum we saw ceramics so delicate they were almost transparent and ornate sculptures hewn from a single piece of jade. Standing in front of a case which holds a 30th century BC representation of our universe – sun and planets orbiting around a disc of jade – I felt overwhelmed by a culture and craftsmanship that extends back in time so much further than my own.

Taiwan’s modern history is as complex and multi-layered as its ancient treasures. After the Museum we ate at The Grand Hotel in Zhongshan District, one of the world's tallest buildings in a Chinese classical style. It was constructed on the orders of President Chiang Kai-shek after his flight from mainland China in 1949. The hotel was built over the remains of the Taiwan Grand Shrine, a beautiful Shinto complex from the early days of Japanese occupation. The Grand Hotel embodies Taiwan’s twentieth century: Japanese colony until 1945, Republic of China and the West’s ally during Mao’s rule, and now; a country in limbo, a modern democracy with a thriving economy which is nonetheless unrecognized by the United Nations and which is regarded by China as an errant son. What then to make of Taiwanese literature, which shares a language its Chinese counterpart but remains distinct from it? Indeed Taiwan, because it is a democracy, does not suffer from the censorship imposed on Chinese editors and authors. If you are a radical Chinese writer, your work is more likely to find a home in Taiwan. If you are a bookseller or publisher, it is in Taiwan that you can exercise independence. If you are a foreign editor looking to translate Chinese authors, you would do well to turn to Taiwan first.

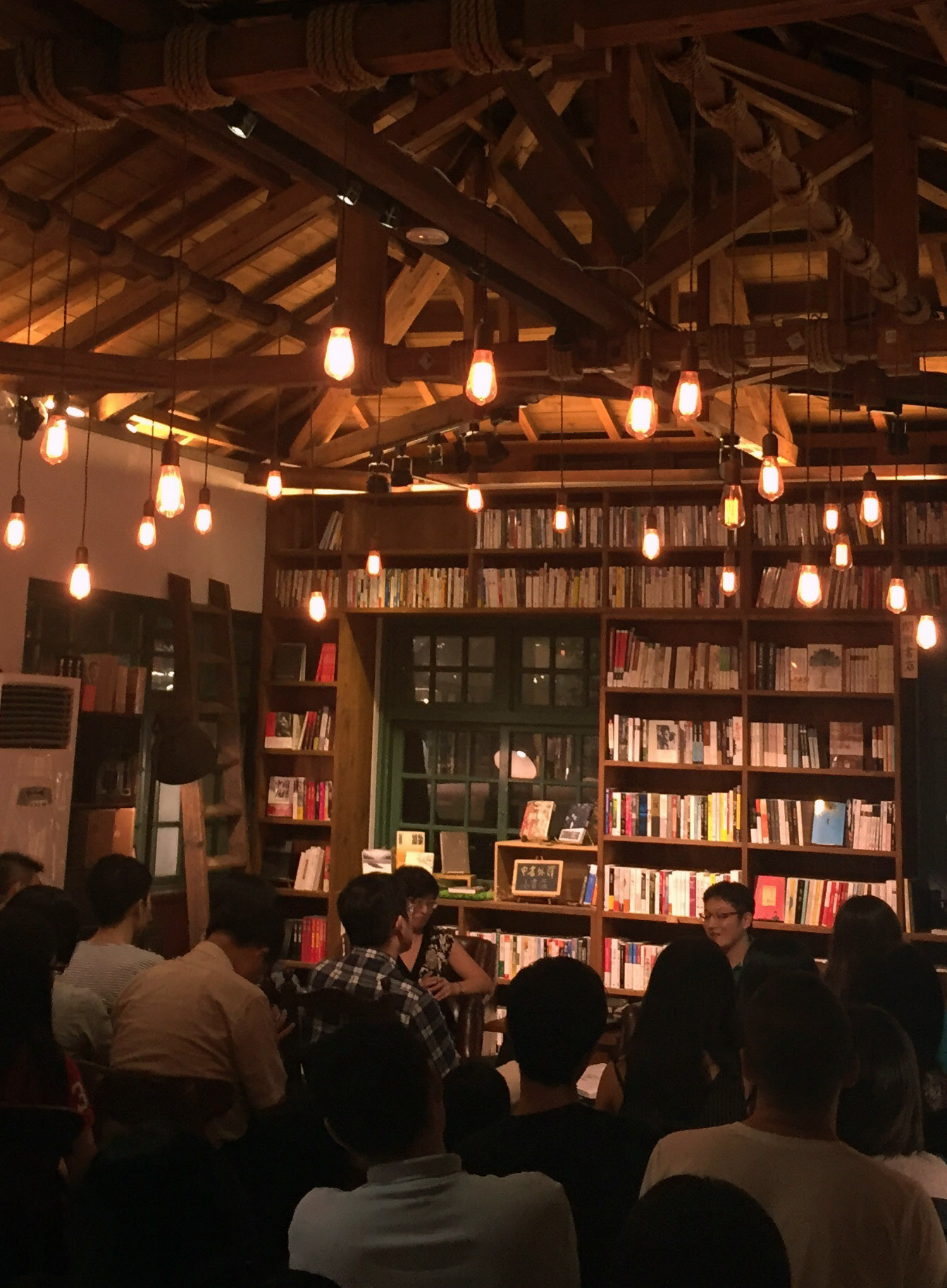

The bookstores we visited in Taipei were bustling. At Eslite’s multi-level flagship store (a chain similar to Waterstones or Barnes & Noble) we wandered through room after room filled with books, many of them translations. Western big hitters dominate in Taiwan as they dominate across the world. The Girl on the Train has sold 100,000 copies(Taiwan’s population is only twenty-four million). Around 40% of the books published here are translated. Of these, 55% come from Japanese and 30% from English, mostly from the United States. Compare this to Britain and America, where a mere 3% of titles are translations. At Crown Culture, publishers of the magnificent writer Eileen Chang, we were told that fiction sales are at an all time low, and sales in general are being driven by film tie-ins. As with most of the Western world, print sales of newspapers in Taiwan are in severe decline, and review culture is vanishing. Book recommendations come from celebrities or social media, and the books that sell best are often film tie-ins, or self-help. Most books will have only a single edition, rather than a hardback followed by a paperback. At Readmoo, an innovative, multi-platform e-book publisher and app developer, they are experimenting with “gamification.” Readers who purchase an ebook are invited to enter competitions and are rewarded with points they can then use against future purchases. The app connects to your social media. It’s Amazon meets Instagram meets Nintendo, and it’s working: their number of readers is increasing month by month. Publishers in the West would do well to pay attention.