While the Taiwanese government’s commitment to a “South Bound Policy” has survived two electoral cycles without wavering, its plans for how to advance that focus and invite deeper cooperation with South and Southeast Asian nations are far from complete. By contrast, certain private and popular interests have been executing their own campaigns in Southeast Asia for several years already. This year the summer session Taipei Rights Workshop for publishing and rights professionals, organized by the Grayhawk Agency, invited Phan Thanh Lan (Vietnam), Fidyastria Saspida (Indonesia), and Jureeporn Somart (Thailand) to share their understanding of current trends in reading and publishing in South Asia with audience members at the Brilliant Time Bookstore, a well-known local purveyor of Southeast Asian literature in its original languages and in translation.

An Up-and-Coming Book Market

Phan Thanh Lan works for Kim Dong, Vietnam’s largest publisher of manga and children’s literature. Founded in 1957, they are responsible for many of the titles that Vietnamese readers grew up with. According to Phan Thanh Lan, Vietnam represents a growth market for the publishing industry. The majority of its 95 million citizens are young, capable members of a burgeoning work force currently driving fast economic development. Unlike in Taiwan, Vietnam’s publishing industry is split between cultural companies and publishing houses; when the former wish to publish a book, they must first acquire a permit via the latter. About sixty-four domestic publishing houses and a multitude of culture companies operate in Vietnam today, with at least one publishing house in almost every province. Educational publishing accounts for a dominating 75% of the market, a testament to the influence of the nation’s school enrollment and testing system. Given annual sales numbers, Phan Thanh Lan estimates that the average Vietnamese citizen reads about four books a year. Meanwhile, children’s publishing now stands at a rising 10% of the total market, a trend she attributes to increased care on the part of Vietnamese parents for their children’s early education.

One significant blemish on this otherwise sunny picture is the slow growth of digital publishing. To date, only twelve domestic publishers have entered the digital publishing space, many fewer than expected. Disparities in literacy between rural and urban centers have made publishing much less profitable in the countryside. Moreover, the nation’s Communist regime mandates that all books undergo central government censorship before publication, leading to situations in which, according to her, “even a fully finished book project can become unpublishable.” Meanwhile, bootleg publishing remains rampant, and continues to escape government control.

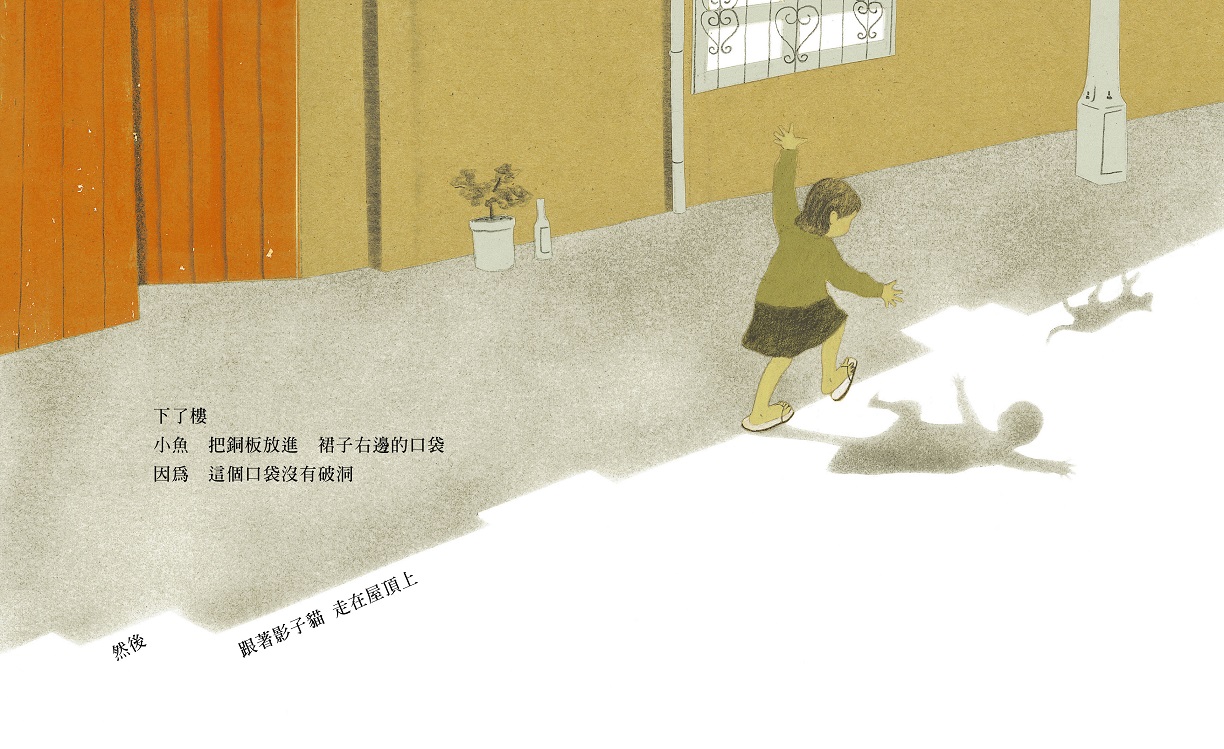

Kim Dong publishes an average of three hundred new titles every year, including a significant number of Taiwanese works in translation. Yet cooperation is not always easy, as deals can get hung up on issues like licensing and list prices. Phan Thanh Lan notes that, for instance, while Jimmy Liao’s children’s titles are extremely popular in Vietnam, Taiwanese publishers worry that the lower retail prices of the same books in Vietnam will end up cannibalizing sales in Taiwan.

Do Indonesians Really Not Like to Read?

Fidyastria Saspida is an editor at Elex, a multimedia company founded in 1985 that has been a paragon of modernization in the publishing industry: In 2001, Elex set up a commercial products department to sell the literacy cards that had become extremely popular among pre-school children, and in 2016, the company started a IP department in order to stay at the cusp of digital publishing. Elex has published a total of nearly twenty thousand titles to date, with an average of 150 new titles emerging each month in every theme and market segment – the new biography of Jack Ma, for instance, was extremely popular with their readers. This trip to Taiwan has left Fidyastria with the impression that Taiwan’s reading environment is not so different from Indonesia’s. Both readerships share a love for genres such as romance and fantasy, leading Fidyastria to conclude that “We ought to have a lot of room for cooperation!” Elex publishes domestic manga as well as translated titles; religious tracts, owing to the strength of Indonesia’s Islamic population, are also quite popular. Furthermore, Elex has capitalized on a recent surge in international tourism to Indonesia by partnering with the Ministry of Tourism to produce guidebooks and other related titles.

“A lot of people say, ‘Indonesians don’t read books, so the market isn’t good,’ but if the market weren’t good, how could we do so well?” She introduces audience members to a number of popular domestic writing and publishing events, including the Bali Readers and Writers Festival, a five-day event on the island of Bali that draws huge crowds of famous authors and enthusiastic readers; it’s “the best reader’s festival in the world,” Fidyastria avers. This year, representatives from Taiwan also attended. One widely-anticipated feature of the festival is a one- to two-day book sale in which prices drop as low as 70% off.

But the Indonesian book market is also not without its difficulties. Since 2015, about half the nation’s bookstores have closed. The majority of publishers are located in Jakarta, the largest city on the island of Java, which means that readers on more remote islands usually have to rely on online retailers to buy books. Significant wealth gaps between the cities and countryside also create significant instability and inequality in the book market, despite its large size. Children’s literature remains the only dependable genre from a sales perspective, though other facets of the market still have room to develop.

Thailand: Facing a Revolution in Publishing Practice

Jureeporn Somart works for SE-ED Publishing House, a business whose name refers to science, engineering, and education. Founded by engineers in 1974, it publishes very popular titles in the hard and natural sciences, as well as in computer science. The business’s crown jewels are its dictionaries, which are the most trusted and best-selling in the country. The Thai people love learning foreign languages, and SE-ED’s TOIEC and English-learning titles are also hot commodities. “After all, these are the kind of books that can get you a raise,” Jureeporn notes.

Jureeporn reports that over the last few years, Thai publishers have begun focusing on their online readership communities. Bricks-and-mortar bookstores, no longer the main vehicle for sales, have become more like exhibition spaces. Publishers have also warmed up to social media as a tool for understanding reader’s appetites more quickly and completely. “Tastes and reading habits are changing,” Jureeporn says. While DIY titles and “boy-love” romances have become extremely popular in recent years, she observes, hard-copy works on cooking, cosmetics, and nutrition have fallen off sharply as readers have turned to online outlets for that sort of information. “They believe the tips and tricks that internet celebrities teach them,” and therefore are less willing to buy printed books. SE-ED caught onto the global social media craze long ago. They encourage online authors to publish previews of their work in advance, so that customers may pre-order titles, which the publisher will then print and distribute according to demand. Jureeporn believes that traditional content and digital content can exist symbiotically; readers still want to feel the weight of a book in their hands, while digital publishing gives them more choices and a different method of reading.

.jpg)