At first glance, the large full moon on the front cover of Sleepwalking may remind you of the classic film E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial which also features a young boy who goes on a big adventure, but the picture book’s plot twists and the pervading ingenuity of its illustrations help make readers feel the warmth of the affection that permeates its pages.

Stories Born from Childhood Memories

Sleepwalking is based on author Yen Chih Hao’s own experience as he often sleepwalked when he was a child and it was something his father worried about constantly. Looking back on it as an adult, Yen Chih Hao wanted to thank his father and cherish the memory of his grandparents who had passed away, so he picked up a pen and composed this story which only took him thirty minutes to write. The publisher introduced him to illustrator Hsueh Hui-Yin and the way they collaborated was quite interesting: once Yen Chih Hao finished writing, he gave Hsueh Hui-Yin full responsibility and the two of them had zero contact until the draft was completed.

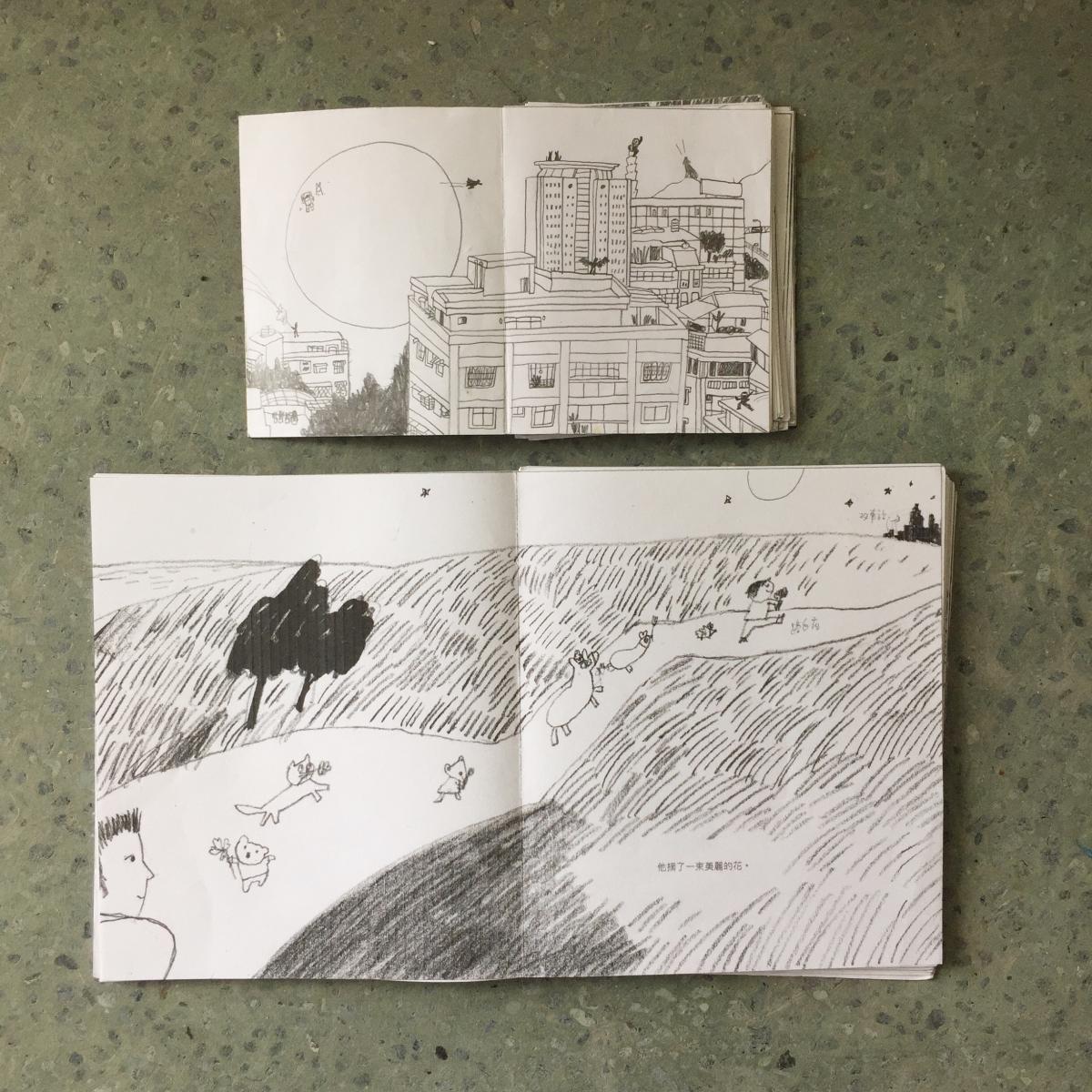

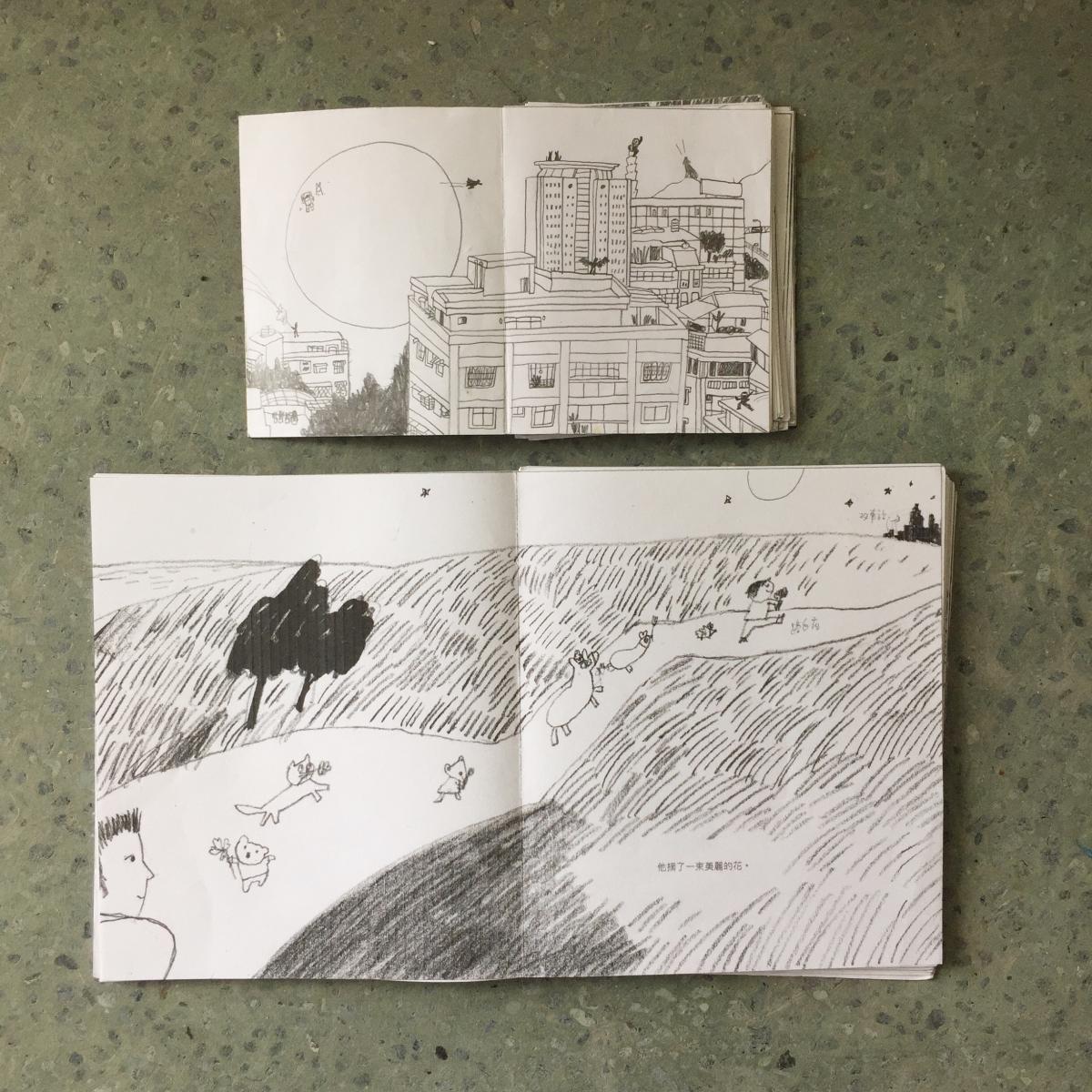

Hsueh Hui-Yin thought that it wouldn’t take much time since the plot was simple and Yen Chih Hao had provided preliminary concepts for the images. She certainly hadn’t expected her progress to be hampered by multiple factors, and the author didn’t push her too much for the sake of quality. Thus, a story which was written in thirty minutes ended up taking five years to illustrate. In fact, it took so long that the editor who’d originally been responsible for the project had gotten married and had children in that time.

The turning point came when the two of them met after the rough drawings were completed. Yen Chih Hao thought the middle of the story was lacking an important turning point: a scene where the father hugs his son. The editor thought it could be omitted, but Yen Chih Hao persisted and decided to discuss it with Hsueh Hui-Yin in person. To his surprise, he found that Hsueh Hui-Yin also felt that they should add this scene and they both regretted not having met sooner.

Conveying Profound Issues in Picture Books

Sleepwalking describes a young boy who sleepwalks out of his house in the middle of the night and embarks on a great adventure. He travels far and wide, his anxious father by his side and protecting him along the way before it transpires that the boy had been going to lay flowers at his grandparents’ graves all along. The father and son embrace and the sleepwalking spell is broken, then their journey home is filled with warm father-son interactions. In the end, the boy returns to his bed and falls back into a peaceful sleep.

At the beginning it seems like an adventure story, but in the middle there’s such an unexpected plot twist and the book ends with an affectionate note between father and son. When asked whether he deliberately planned it this way, Yen Chih Hao quickly replied that a common motive in life is to supplement our inner selves and as we slowly accumulate this material over time it naturally reveals itself so there’s no need to purposely construct something new.

Surprisingly for someone who had already written many works over the course of his career, Yen Chih Hao’s appreciation for children’s literature occurred relatively late. It wasn’t until he pursued a graduate degree in children’s literature that he really came into contact with it and began to slowly figure out his own creative path. It could be said that children’s literature is his safe haven and that he wants to give children hope and spark their imaginations through his works, and that this is where he finds his own creative joy.

While the book explores profound issues such as death and parent-child interactions which might seem a bit serious or difficult for young children to understand, Yen Chih Hao tries to tell the story in the style of a fairy tale. He takes a warm approach to reflecting on life and makes the child’s thoughts the main highlight, which he particularly emphasises by having the father stay silent on the journey. It’s not just about hoping that parents can let their children fly, it’s about wanting children to always have that strong backing and support.

The Shared Dance Between Author and Illustrator

In terms of collaboration between an author and an illustrator, Yen Chih Hao believes that an illustrator should respond to the text and the pictures should bring an additional layer of creativity. With Sleepwalking, Yen Chih Hao left Hsueh Hui-Yin a lot of space for expression: “It’s like two people dancing together, it’s just that I danced the first half then stepped aside so my partner could dance the second half.” He hoped that by having their two life stories intertwine, they could create an even more beautiful third story. A good picture book should be like a film, where the text gets the ball rolling and the images immerse the reader in the story.

The book contains relatively few words and the latter half of the return journey is told entirely through images which gives the narrative a unique style of its own, although this lack of text also puts the illustrator’s storytelling ability to the test. Hsueh Hui-Yin initially painted the images by hand but discovered the pictures looked too crowded so she did the illustrations digitally to reach the perfect balance. If you look carefully, you’ll see that the pictures contain a lot of hidden details which Hsueh Hui-Yin deftly uses to bring the images to life, including the boy’s stuffed animals, the way the moon moves across the night sky to signify the passage of time, and the illustrations in the second half which are in the opposite direction to show that they’re on the return journey.

Hsueh Hui-Yin believes that relative to creating a single illustration or a book cover, illustrating a picture book is more like making an album. A picture book is a complete story, so it is important to pay close attention to the narrative structure and cohesion between plots. The composition and arrangement of images need to be carefully considered and the pictures must convey what cannot be expressed by words.

Sleepwalking’s landscapes are often filled with features that are distinctly Taiwanese, such as its wind turbines, trains, and convex traffic mirrors, all of which remind readers of the island’s beauty. Combining this with the universal feelings conveyed by the story itself and the straightforward illustrations will surely help the book transcend language barriers and impress readers from all over the world.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)