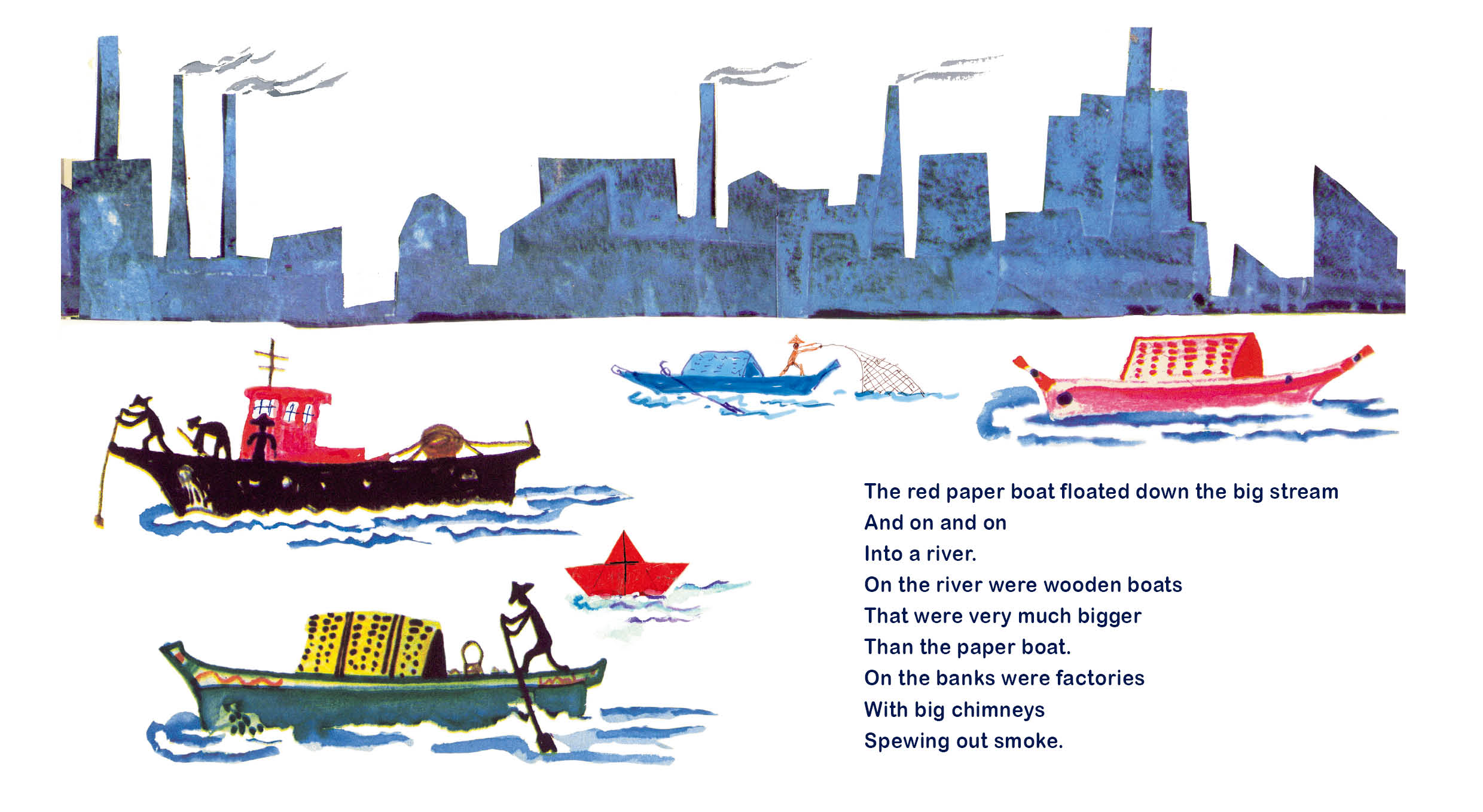

As this book’s title suggests, Jianghu refers to a locale. Literally translated as “rivers and lakes”, the term Jianghu has rich connotations, encompassing natural and human geographies as well as alternate universes with distinct codes of conduct, choices, and consequences. At the same time, Jianghu is a generic expression and a quintessential component of the Wuxia genre in Sinophone literature, film, theater, and other popular entertainment including comics and online games.

Depending on the context, modern references to Jianghu are found in fantasy, realistic fiction, poetic or prosaic descriptions of social environments or professional arenas, and even individual interior worlds as experienced in this Wuxia novel for tweens. In fact, Jianghu can define both the setting and the conceptual construct shaping the narrative lens: where the stories occur as well as how they are told. Adopting this milieu indicates the presence of alternative – sometimes intersecting – realities that occupy diverse dimensions of existence and realms of imagination.

Jianghu, Is There Anybody There? by Chang Yeou-Yu embodies the distinguishing features of Wuxia novels, beginning with a colorful cast of characters possessing different types and levels of Kong Fu, a euphemism for honing the requisite skills for one’s pursuits. In the Wuxia genre, Kong Fu refers to the practices as well as the outcomes of training one’s body and mind based on the disciplines of particular clans, schools, or sects of martial art. Written for tweens, this work centers 13-year-old Tsu Hsiao-Pi, who is kindhearted, reserved, and industrious. Abandoned as an infant and raised by the master cobbler of NiuTou Village, he becomes highly skilled at shoe repair and design, and is poised to take over the workshop as the story begins. Unlike his Kong-Fu-obsessed neighbor and childhood friend Kang Liang, who at age 13 is keen to leave his family’s steamed bao (buns) business in order to explore the Jianghu and compete for fame and glory as a martial artist, Tsu Hsiao-Pi is content to cultivate his craft and care for his aging mentor whom he considers his father. His other close friend Mai Tien, a compassionate, clever, and quick-witted 14-year-old, also compels Tsu Hsiao-Pi to stay put, although he does not readily admit it to himself.

Strategically situated along an ancient thoroughfare, NiuTou Village supplies essential services for travelers on their way to more prominent destinations. When suspicious circumstances bring a questionable visitor to the cobblers’ workshop, Tsu Hsiao-Pi is suddenly gifted with amazing Kong Fu he had not sought. Soon, he is forced to confront a complicated Jianghu and struggles to make tough decisions, such as whether to tell anyone about his newfound superpowers. While witnessing Tsu Hsiao-Pi’s character development and evolution as a reluctant hero, readers learn of the region’s legendary martial arts competitions and the champions whose names were inscribed on an iron pillar that once upon a time stood by the village’s LiangCha Pavilion. The whereabouts of that pillar becomes the point of contention as conspicuous characters stream into NiuTou Village and fill up the local inns, much to the dismay of the police chief-cum-village head Chien Chih.

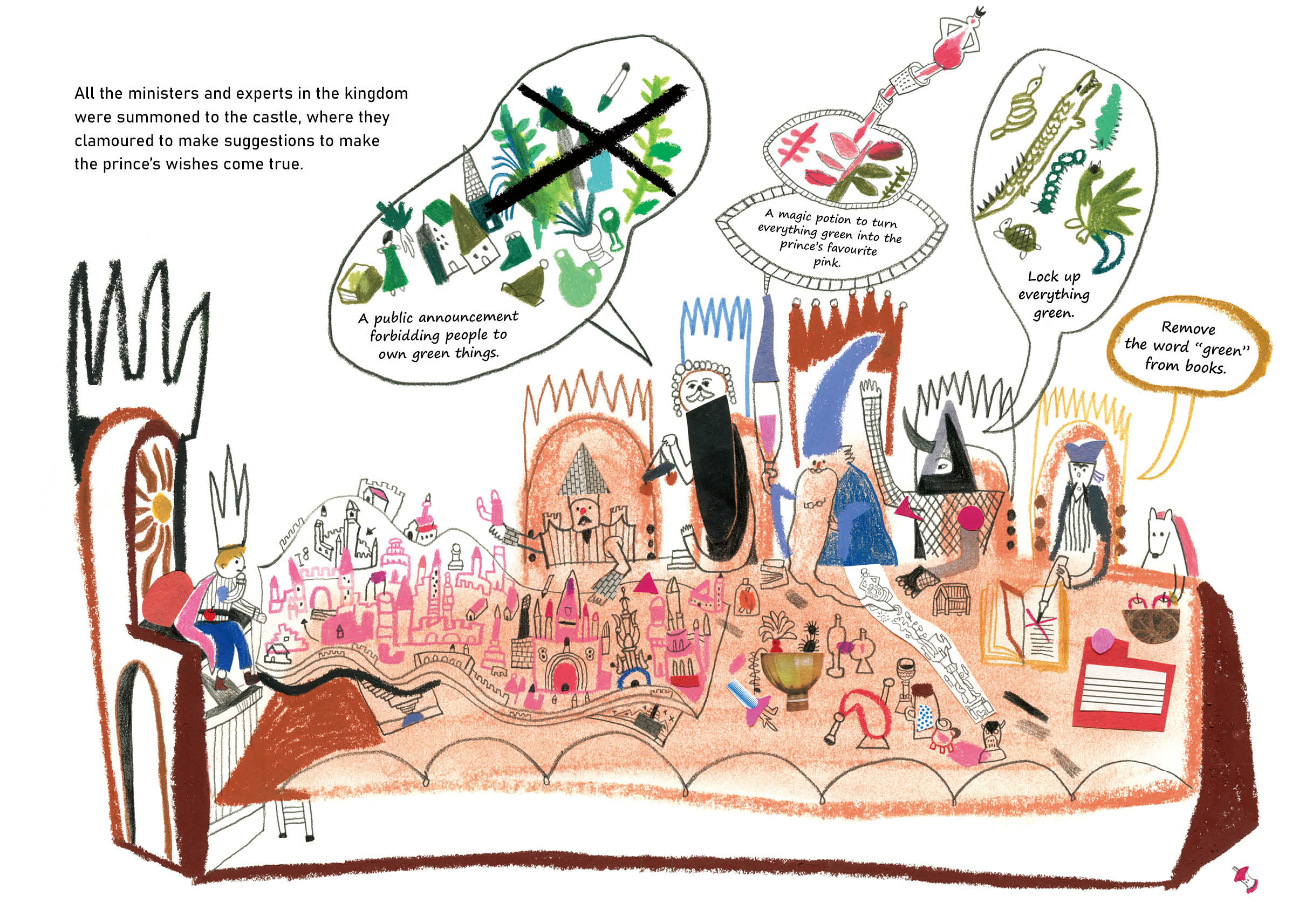

Recalling the senseless violence often accompanying martial arts competitions in the past, Chien Chih has outlawed them by decree. Meanwhile, he has put in place a separate iron pillar inscribed with the names of the officers who had perished while protecting innocent bystanders and inexperienced contestants as the competitions had grown increasingly deadly over the decades. Challenging Chien Chih’s one-sided representation that privileges strict law enforcement over respect for the Jianghu’s chivalric ethos and values, the proponents of the martial arts competitions rally to re-stage the tournament in order to restore their honor and reputation. Moreover, they insist on reinstalling the missing pillar and are willing to take extreme measures to make that happen.

Against this backdrop of adult-world disputes and imminent threats to the community, readers zoom in on the lives of the main characters and their everyday activities. We observe intricate details of Tsu Hsiao-Pi working on special shoes that help Kang Liang with his Kong Fu practice, Mai Tien weaving lifelike animals and tiny shoes with the straw she freely collects from the workshop, and Kang Liang delivering stacks of bao-filled steamers while improving his balance and agility. We also witness adolescent angst and increasing tension between best friends as misunderstandings arise and loyalties are questioned.

Like its counterparts for adult readers, Jianghu, Is There Anybody There? establishes an atmospheric Wuxia story world featuring landscapes with provocative place names, such as Twenty One Peaks, Laklak River and Ancient Road. Sketches by Lin I-Shian reflect traditional Wuxia illustration styles and flesh out the key characters. Author Chang Yeou-Yu distills the genre’s epic themes – individual and collaborative quests that involve navigating treacherous surroundings, lingering memories of old scores to be settled, plus conflicts that arise from the ambiguities inherent in rules and regulations vs. justice and truth – into intriguing narrative strands, spinning them into an action-packed plot with reveals and twists that are age-appropriate and relatable for the target audience. Through the sympathetic characters, Chang not only demonstrates some of the finer points of Kong Fu practice, but also outlines various philosophical approaches to life in the Jianghu.

The result is an engaging and entertaining journey through a Jianghu that welcomes anyone who wishes to visit.

.jpg)