You may have heard of India’s Bollywood, or even the Nigerian Nollywood, but did you know that, once upon a time, Taiwan also had a Hollywood?

The story of cinema often gets explained in a kind of film-lovers short-hand: Singing in the Rain shows us the transition from silent films to talkies, right down to the elocution lessons. Cinema Paradiso is a nostalgic look at the era of celluloid film. Day for Night shines a light on the outsized passions that fueled the production of great films… ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD TAIWAN, however, reveals an overlooked sub-plot in this familiar story. Readers will learn that while the Western cinema was exploring new avenues in the post-war era, filmmakers in Taiwan were brimming with creative energy, churning out Hokkien language films to the order of a hundred films per year for markets that spread beyond Taiwan to Southeast Asia. This once flourishing industry, however, fell victim to government imposed language politics and regulations on technology. As a result, an entire generation of films was stamped with pejorative labels: poorly produced, low-class, outdated – and then forgotten.

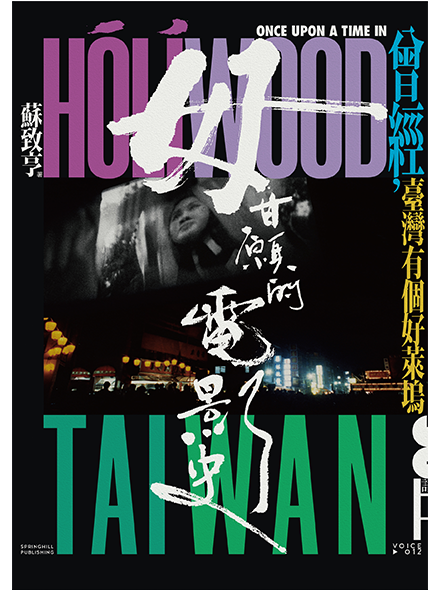

ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD TAIWAN

Our Stories, Our History

When it comes to this early period of Hokkien language film, you’ll find that even Taiwanese people have rarely heard of it. How was this period of our own history silenced? “This feeling of being a stranger in one’s own country is quite common for many Taiwanese people of my generation,” says author Su Chih Heng, former researcher at the Taiwan Film Institute and M.A. graduate of National Taiwan University’s Institute of Sociology. It is exactly this situation that compelled Su Chih Heng to commit the seven years of research and writing necessary to complete his book. Unlike other cultural histories of Taiwan, you’ll find no pontificating on elite culture in ONCE UPON A TIME IN HOLLYWOOD TAIWAN. The book takes popular culture as its subject, and the film-making industry as its primary locus of analysis, re-establishing the cultural pedigree of the early period of Hokkien language film.

“Cultural histories of Taiwan have typically centered on Mandarin speakers, adopting a historical perspective of Chinese nationalism, which obscures the experiences of the majority population, the authentic representation of Taiwanese culture,” says Su Chih Heng. In comparison to the voices of Taiwanese writers, who were effectively silenced under the “language movement” promoted by the Kuomintang Administration, filmmakers in 1950’s Taiwan produced a sizeable number of Hokkien language films.[1] More than just a flourishing of nativist culture, these movies spanned a broad range of subjects. “Americans had their Laurel and Hardy, and we had Brother Wang and Brother Liu Tour Taiwan (王哥柳哥遊臺灣). While Zatoichi, the Blind Swordsman held sway in Japan, we had Three Beautiful Blind Female Spies (豔諜三盲女), a local remake involving blind women swordsmen.” Su Chih Heng also points out the influence of mainstream consumers: “This (range of films) reflects consumer preference for local language culture, as well as the creative dynamism of the Taiwanese people.” From these examples we can see that Hokkien language production houses were actively engaged with other film markets, and exhibited great flexibility in mobilizing their resources, enabling them to keep pace with current trends.

.jpg)

Movie Poster of Three Beautiful Blind Female Spies

(Resoures: Taiwan Film Institute)

In the 1960’s, in response to the advent of color television, American film studios also began their gradual transition to color film. Advances introduced by Eastman Kodak, the sole company with the imaging technology to produce color film stock, dramatically lowered the barriers to making color movies, with the result that the rest of the world soon followed in America’s footsteps, transitioning from black and white to color filmmaking. On the topic of this epochal transition, Su Chih Heng points out the unique circumstances faced by the Hokkien language film industry in the midst of the language unification movement. The Kuomintang Administration, which had become involved in managing the movie industry in the post-war years, restricted the use of color film to movies shot in the “national language” of Mandarin, amounting to a form of covert suppression of the predominantly black and white Hokkien language movies. At the same time, foreign currency controls were imposed that made it more difficult to import black and white film stock, forcing a rapid deterioration of the Hokkien language film industry.

Read on: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/latest_info.php?id=101

[1] Influenced by nationalist ideologies, language unification movements took root in many countries in the post-war era, including France and Spain, which resulted in the suppression of local dialects. The National Language Movement in Taiwan began with the formation of the Taiwan Province National Language Promotion Committee by the Kuomintang Administration in 1946, which established Beijing Mandarin as the standard for the National Language Movement. Hokkien, Hakka, and other regional dialects were prohibited out of fears that “Without a unified language, there can be no unified nation.”