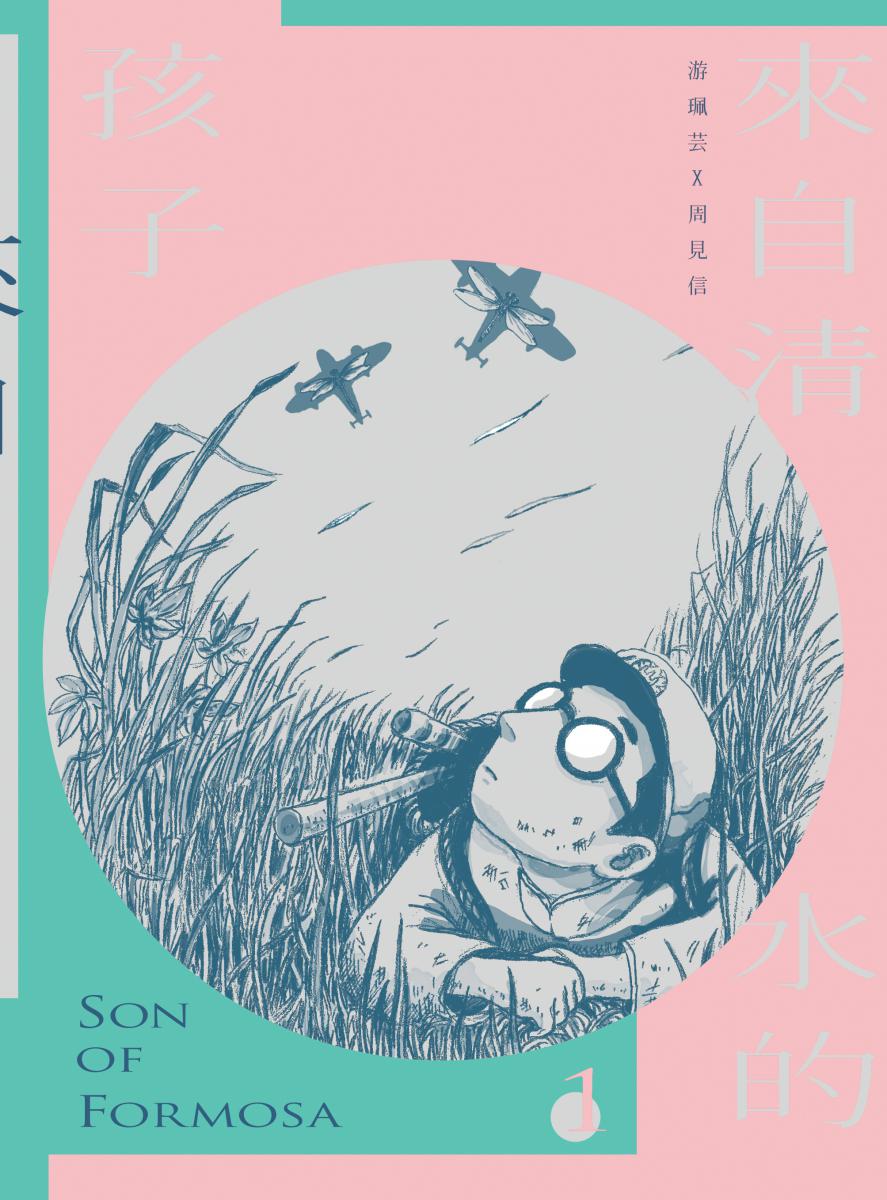

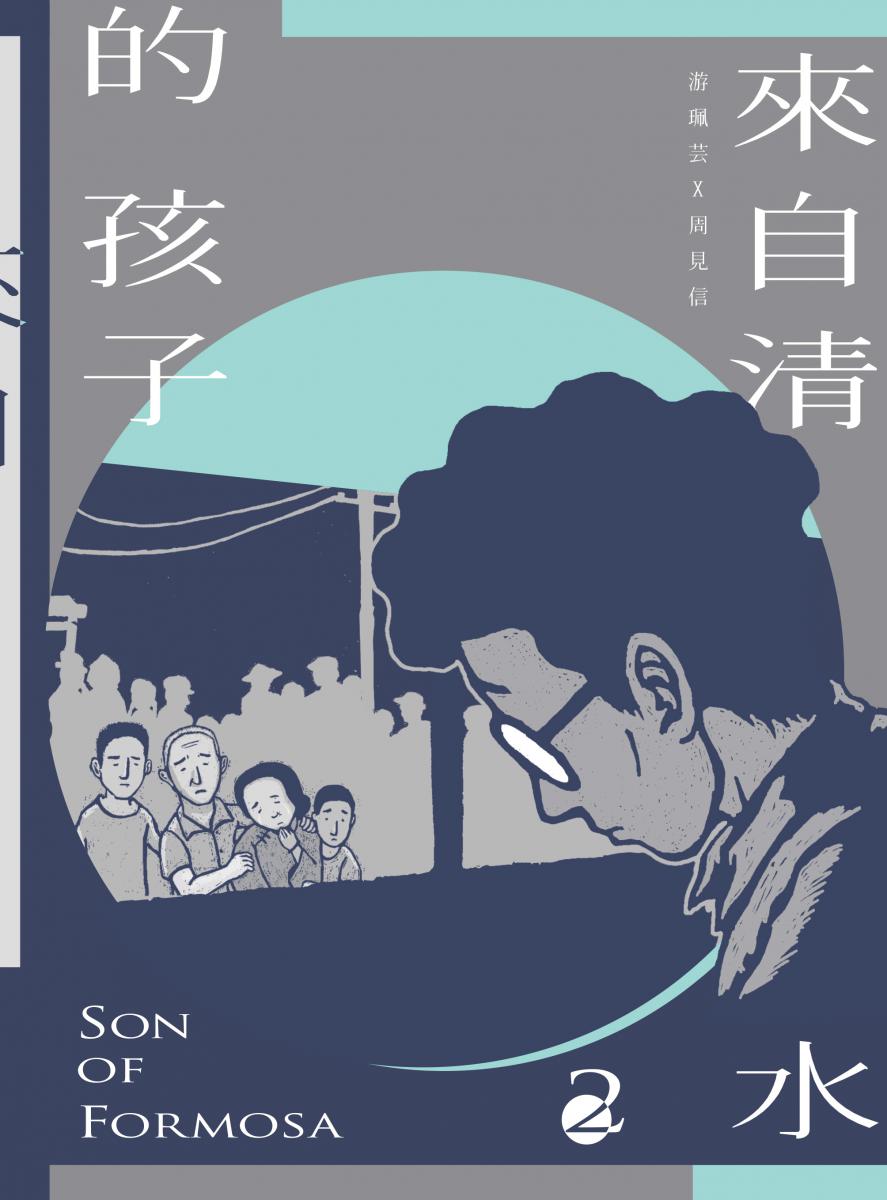

Son of Formosa, the first graphic novel series from Slowork Publishing, depicts the milestones of Taiwan’s modern history seen through the life story of Mr. Tsai Kun-lin. Within its pages, readers witness the shifting panorama of the eras of Japanese colonization, post-war retrocession, the White Terror, the lifting of martial law, and the coming of democracy. Combining the spare but powerful text of author Yu Peiyun and the sensitive artwork of Zhou Jianxin, the four volume series is more than the story of one man – it is a vessel for the memories of an entire generation of Taiwanese.

An Ordinary Life: History in Miniature

Author Yu Peiyun laid eyes on Mr. Tsai Kun-lin for the first time in 2016. At the time she was assisting with an exhibition of writings by victims of the White Terror being held at National Taitung University, and Mr. Tsai attended the opening as an honored guest. The man Yu Peiyun witnessed that night was spry, radiant with energy, at once modest and warmly engaging. Having some understanding of his life experiences, she couldn’t help but wonder, “How could someone who had endured so much give the impression of such warmth and wisdom? Coming into contact with him was refreshing, as if he had the heart of an innocent child.” As she listened to him sharing his memories, the impulse kept welling up inside her to record the story of his life.

(from left to right) Yu Peiyun, Tsai Kun-lin, and Zhou Jianxin

As both a scholar and author of children’s books, Yu Peiyun had discovered that most of the children’s literature available in Taiwan came from overseas. “But we have such rich history and stories of our own,” she relates, “They should be written down.” For this reason she decided to collaborate with Slowork Publishing to produce a book focused on Taiwan: a detailed life history of Mr. Tsai Kun-lin that would serve as a portrait of an era in miniature.

Sleuthing for Source Materials: Piecing Together Taiwan’s Unique History

A work of historical biography cannot be undertaken without first gathering a rich array of source materials. Mr. Tsai had already published a personal memoir, so Yu Peiyun focused on researching details of everyday life that she could write into the story in hopes of striking a chord with readers. One such detail appears in the second volume, as political prisoners are moved to Green Island for internment. Upon seeing the prisoners, the local inhabitants are shocked. “They’re so pale. They look like white woodlice,” they say, comparing the malnourished prisoners to the thin-limbed crustaceans that inhabit the island. In confusion they ask, “They’re all people? Why were we told they were apes (sing-sing)?” The island’s inhabitants had been told that “new students (sin-sing)” would be arriving, a euphemism for prisoners which is also a near-homophone for apes in Mandarin. Humorous details such as these come directly from Yu Peiyun’s research, and were incorporated to more accurately recreate the atmosphere of the times. Yu Peiyun jokes that her research was a bit like solving a historical mystery. Since Mr. Tsai couldn’t possibly provide all of the details to recreate an entire era, it was left her to track down the missing pieces of the puzzle. Fortunately, Yu Peiyun relishes detective work.

In addition to finding historical information to weave into this moving tale, Yu Peiyun put a great deal of thought into the presentation of the story. The title, Son of Formosa (Child of Qingshui District in Chinese) indicates how she differentiates her approach from that of conventional memoirs covering this period of history. She hopes to clear away the clouds of misery and suffering associated with the era, erasing the usual labels, and instead convey that same impression of purity she had on first meeting Mr. Tsai. Although he had lived through political and national upheavals, in the end he was still that innocent child of Qingshui District–a son of Formosa.

A number of period songs also appear in the books. Yu Peiyun relates that Mr. Tsai is a music lover with a fine singing voice, for whom music has an almost redemptive power. Inserting interludes of song into the story highlights this aspect of his character, showing readers how his singing restored his spirits in times of hopelessness and kept the taste of freedom alive in his heart through the darkest years of his imprisonment.