When CommonWealth Education Media and Publishing was founded, its goal was to serve as an educational community for parents and children, to provide “a knowledgeable support system, a platform for exchanging methods, and a community where people can share their feelings.” Books and magazines are currently one of the most efficient tools for learning, and CommonWealth Education hopes that it will have the flexibility to provide children with everything they need to develop healthy reading habits while simultaneously helping parents and teachers enrich themselves in the process.

The Early Stages of the Taiwanese Children’s Book Market: The Predicament of Developing Domestically Produced Books

From a publishing context, the Taiwanese children’s book market was severely dependent on imported works during the early years and it was virtually impossible for Taiwanese authors to make it onto the bookstores’ general bestseller lists. However, right from the beginning CommonWealth Education has insisted that at least 50% of the titles it publishes each year must be by local authors. It’s hoped that the content of these locally-produced works is a reflection of the environment the children grow up in, which helps give young Taiwanese readers a deeper sense of recognition and emotional connection to the place while they’re reading, and in turn this nurtures their growth. It’s also hoped that parents can connect with their children through these reading materials about life and child-rearing, and that they can ultimately be used to resolve all kinds of everyday problems.

Over the last twenty years, a whole new world of locally-produced works has opened up. Take picture books for example, CommonWealth Education has republished new editions of many of Lai Ma’s classic works including I’m Breathing Fire!, The Day I Got Up Early, The Monster of Palapala Mountain, Mr Hurry and Guess Who I Am? in the hope of bringing these classic stories to a new generation of children. CommonWealth Education has also expanded on Lai Ma’s works and designed lots of spin-off merchandise based on the picture book characters, to help the author go beyond picture books and take their products in a more varied direction. After the success of Lai Ma, CommonWealth Education hopes to continue to create diversified spaces and platforms for other high-quality IP and help Taiwan keep reaching new creative milestones, that by trying more varied and innovative methods it will break through the framework of traditional media and publishing to build a new content industry in the digital age.

Demand-Based Reading Material Created Exclusively for Children

In terms of publishing for school-age children, CommonWealth Education uses its existing interest in educational fields to provide age-appropriate books for the child’s reading needs. Reading 123 is a series designed for children in the early years of elementary school who have crossed over into reading chapter books. The series helps children become independent readers by designing the book to have a certain number of words, vocabulary that’s not too difficult, and supplementing the story with lots of illustrations. The books are 100% locally produced and serve as a bridge by developing a space where children can read word-based books unhindered and creating a lot of characters who are beloved by elementary school children, such as the little fire dragon and Captain Fart.

CommonWealth Education provides different reading materials for children as they get older. During the critical phases in their reading journeys, it becomes more important to help children connect with guides so that by the time they’re teenagers and entering the rigid life of secondary school, they’ve been able to read a wide range of books which have given them an appetite for reading. CommonWealth is keen to create works which contain Eastern elements so that children can learn about the region’s rich literary history alongside the Western culture they already absorb.

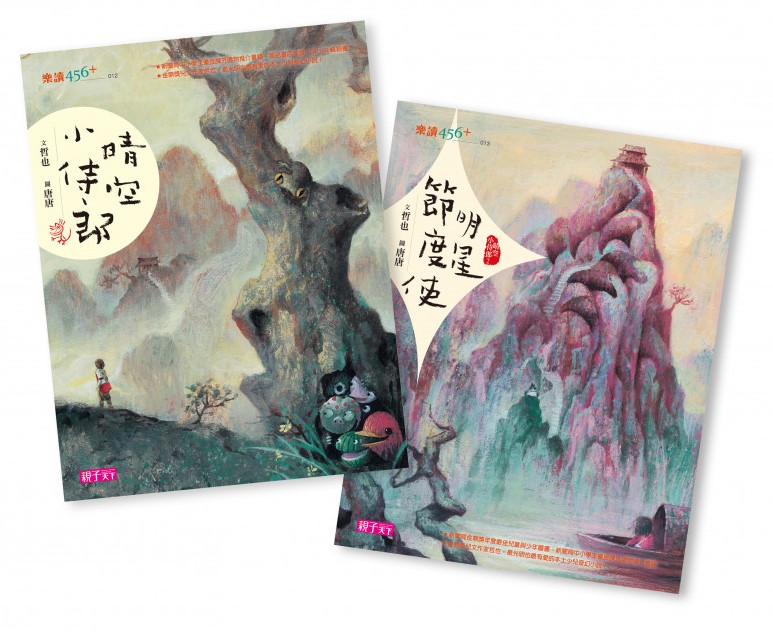

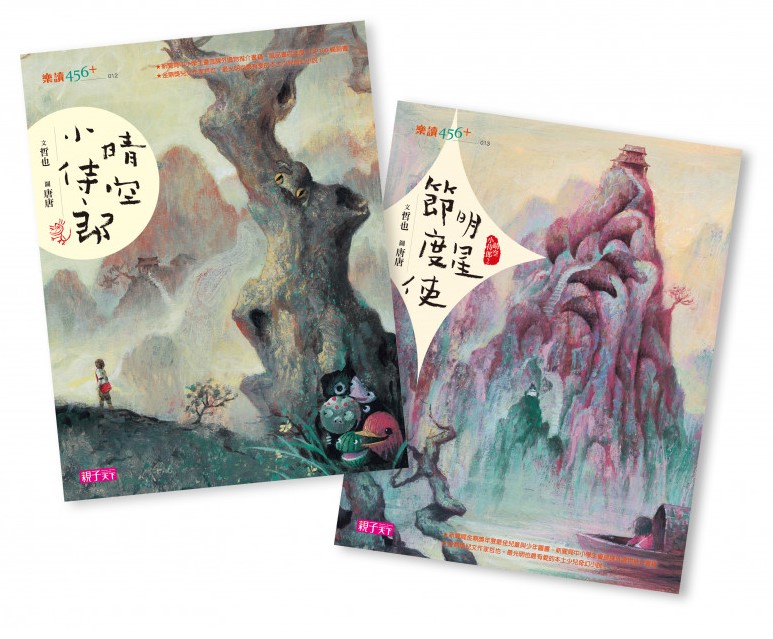

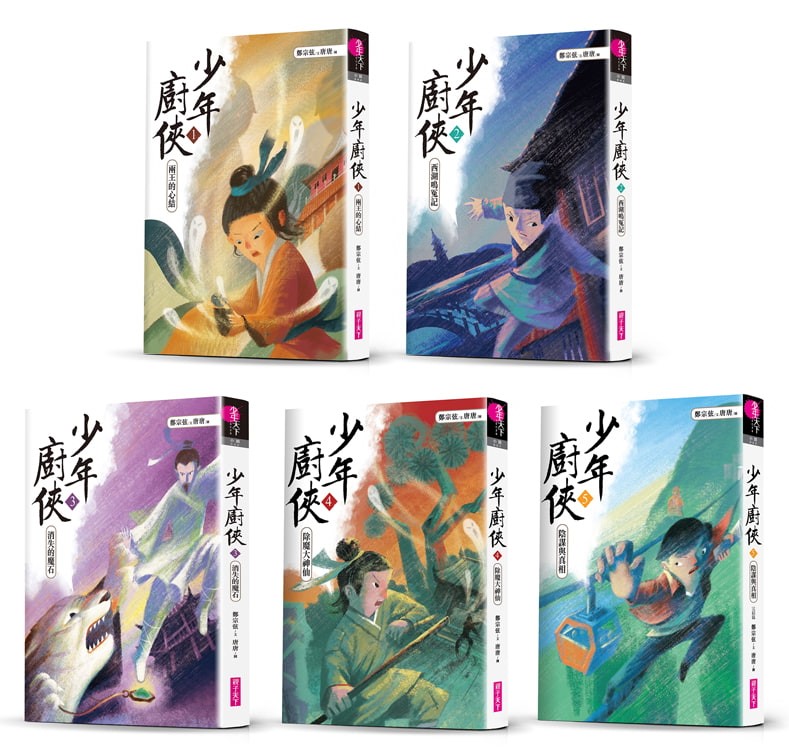

In this vein, Jay Yeh’s classic series The Little Deputy of Sun Dynasty guides the reader through the history of traditional Chinese monsters and contains a rich selection of legends and folk tales, as well as interesting stories and poetry. Kevin Cheung’s light martial arts series Young Kitchen Warriors retains the chivalrous spirit of the genre and incorporates the Eight Great Traditions of Chinese Cuisine, introducing the interesting stories behind famous dishes and building important historical bridges which allow children to experience thousands of years of food culture through reading. Chen Yuru is the first female Chinese author of fantasy for younger readers and wrote the Legends of the Immortal Spirits series which uses classical literature to construct a fantasy kingdom. She takes Tang and Song Dynasty poems and converts them into brilliant adventure settings which the protagonists have to travel within to solve mysteries, giving the reader a real sense of the beauty of classical literature. These middle-grade texts capture the depth of the stories without being difficult, which gives children the ability to use their reading to grow.

Laying the Foundation for Children’s Reading Literacy by Integrating Educational Expertise

As well as publishing children’s books, CommonWealth Education is deeply engaged in publishing titles on education and parenting. This year, the most avidly discussed topics among parents and teachers are the “108 Curriculum (officially called “Master Framework for the 12-year Basic Education Curriculum Guidelines”)” and “Reading Literacy”. Children are facing exam questions that are significantly longer than they were before and with far more complicated narrative context. Every subject now tests for “literacy”, whether it be in Chinese language, mathematics, social sciences, natural sciences and so on. The content is all-encompassing and it’s expected that the school will guide the children towards knowledge, so they can apply it to resolve issues in all areas of their lives.

However, from a child’s perspective these kinds of “open-ended” literacy questions are extremely testing. They must read the text and have a comprehensive understanding of what the piece is ultimately talking about before they have the chance to use their own knowledge to come up with a corresponding solution. CommonWealth Education plays to its strengths by taking a thematic approach and putting complicated subject-matters in simple terms to provide “digestible” content. In response to this modern societal trend that values literacy, reasoning ability, integrated understanding and practical application, there should be a strong emphasis on children reading “a diverse range of interdisciplinary texts” as part of their daily extracurriculars and they should gradually progress from short stories to longer texts, giving them the opportunity to make up for the deficiencies in classroom learning and textbooks.

Zeng Shijie’s Comics for Chinese Language and Literature: A Story Collection uses structured, story-like texts and comic-strip reading exercises to help children quickly grasp the key points and structure of an article. The series also gives them the chance to practice reading long texts and increases their ability to understand, repeat and summarise, all of which lays a strong foundation for reading literacy.

In the past, CommonWealth Education has watched education and parenting trends then used this information to help Taiwanese educators look at directions for the future. It also put a series of plans in place to assist local creators in developing a supply of diverse content to meet the reading needs of children of all ages. Going forward, CommonWealth Education hopes to use these core goals as the basis for broadening the horizons of Taiwanese education and children’s books.