Japan had been a major country for literary translation since the Meiji period, actively introducing works from Europe and America. However, since the collapse of Japan’s economic bubble in 1991, translated books have fallen out of favour for a variety of reasons, such as the high cost of producing translations which led to a slide in sales as younger people went into poverty, and a shift in general interest from the international to the domestic. Although there has been no shortage of discussion and ongoing research, ultimately, it is safe to say that it has been a sluggish 30 years for translated books. In the last five years, there has been a profound sense of crisis among translators, editors and their counterparts. They have banded together across different language families and gradually formed discussions and a movement popularising translated literature from abroad, to the point where The Best Translation Award has been established, and a lot of Japanese publishers have steadily regained interest in translated works.

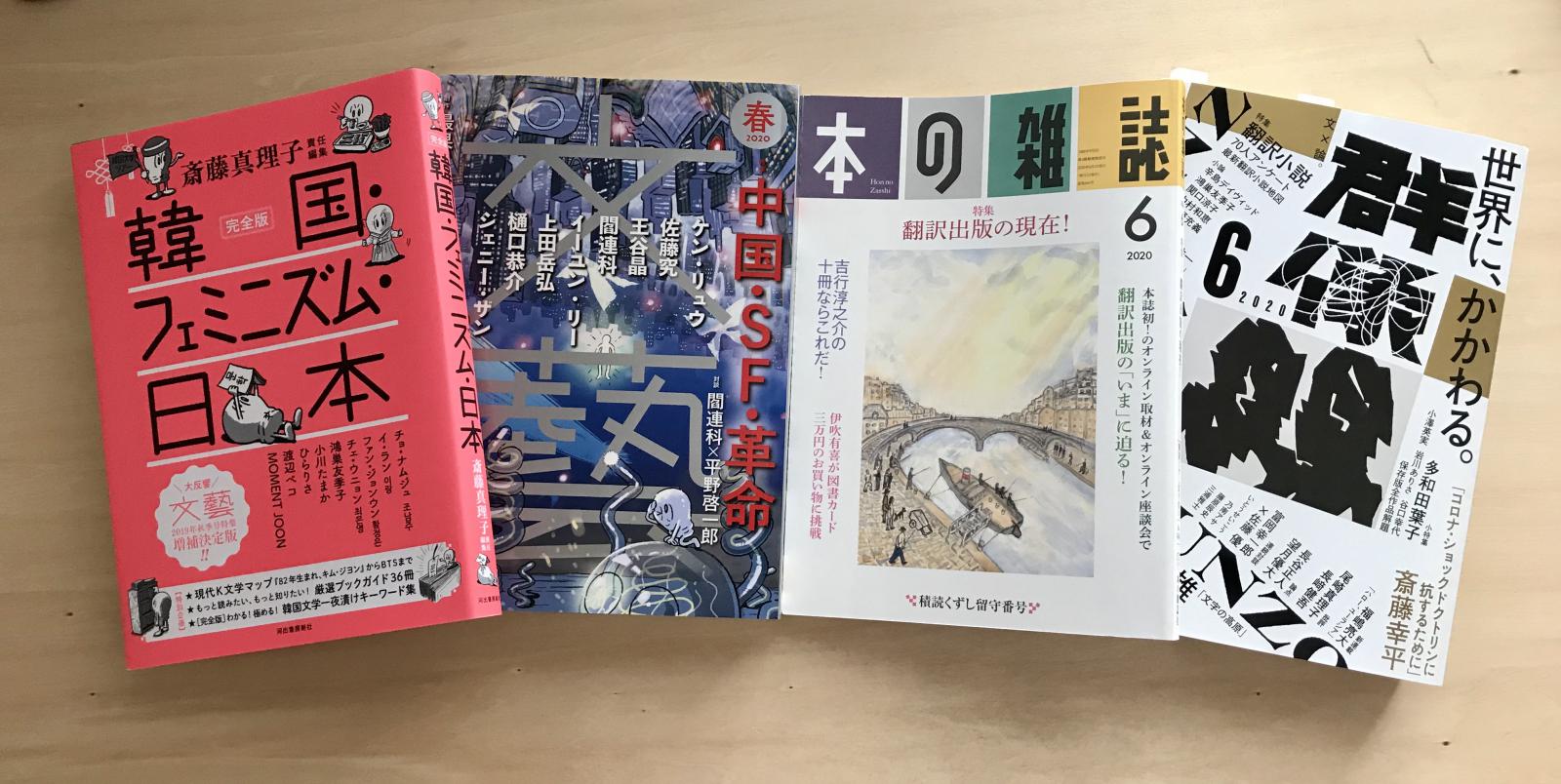

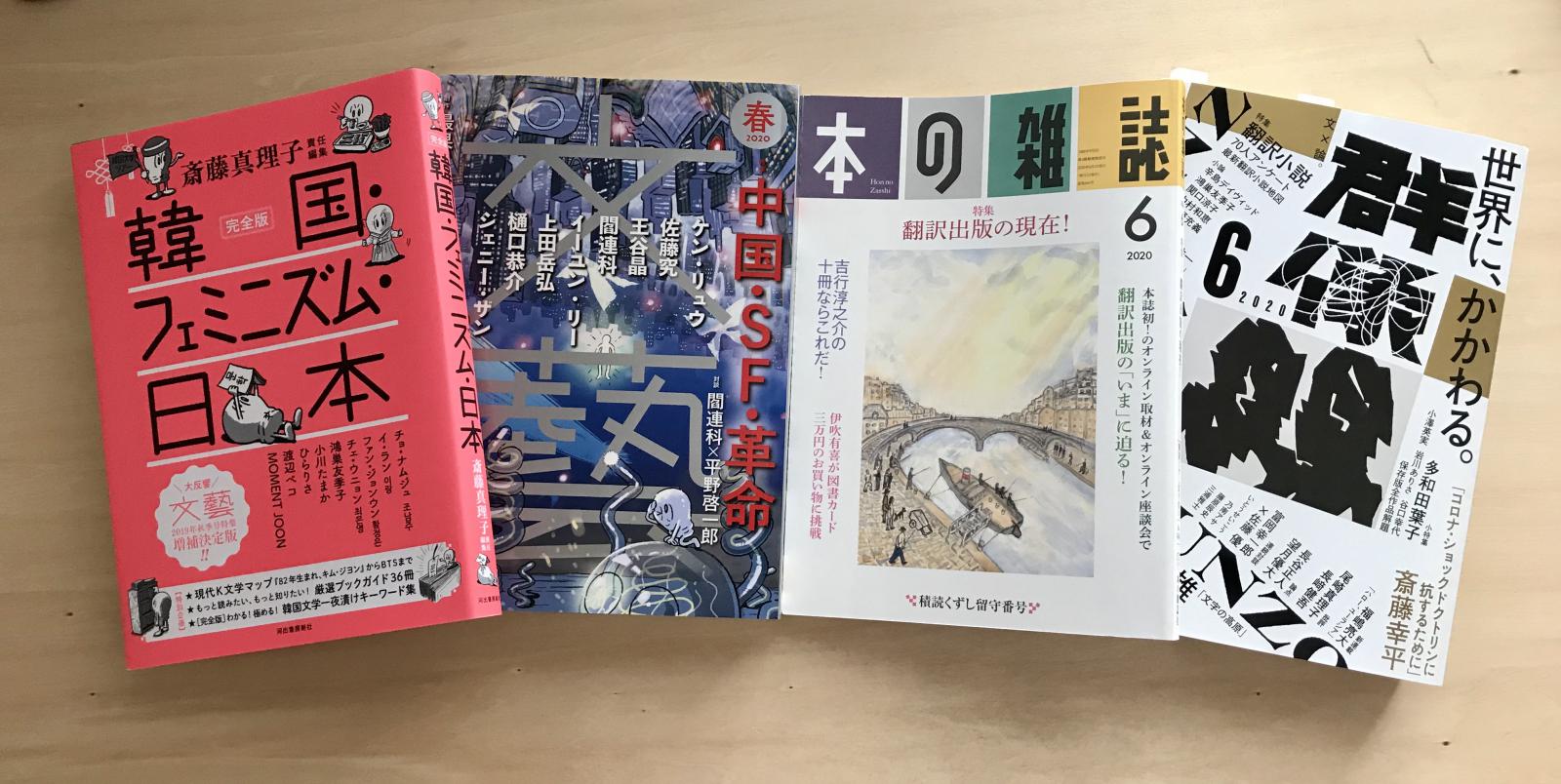

From left: Bungei "Korean and Japanese Feminism", "China’s Sci-Fi Revolution", Hon no Zasshi, Gunzō

By chance, the June 2020 issues of the literary magazine Gunzō (published by Kodansha) and the publishing news outlet Hon no Zasshi featured special editions on “Translated Fiction” and “Publishing Translations Today!” respectively. The newly revised quarterly magazine Bungei (meaning “fiction”, published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha) also forged forward on this front, with its Autumn 2019 issue on “Korean and Japanese Feminism” that featured fiction translated from Korean, and its Spring 2020 issue on “China’s Sci-Fi Revolution” covering translated Chinese novels. These issues not only included a lot of newly translated fiction and essays, but also book reviews, discussions and exclusive interviews. In the 86 years since the magazine was first published, this was the first time an issue had been reprinted three times, with a total print-run of more than 10,000 copies, eventually marking a small step forward in the craze for translated works from Asia.

I will combine the topics raised by the literary magazines above with my own observations from the last few years, as well as the current state of publishing in terms of individual books.

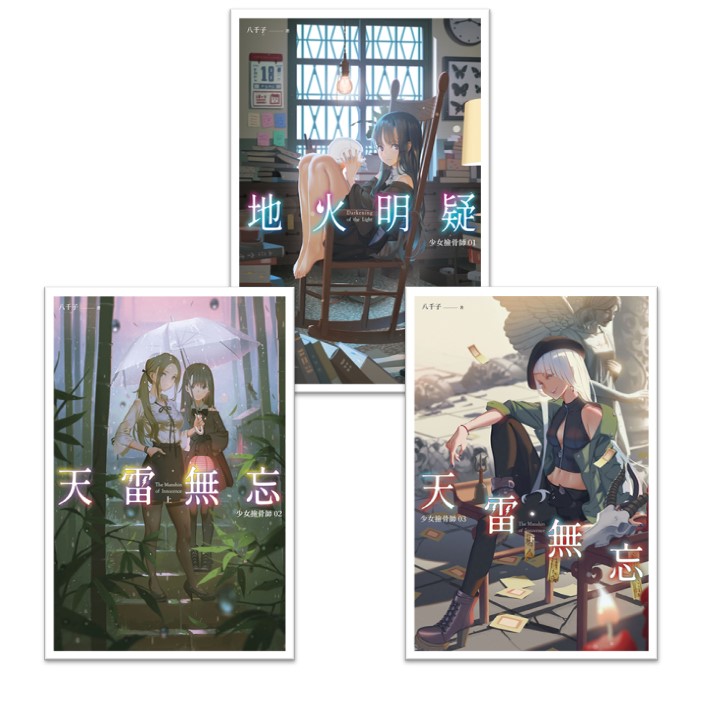

In South Korea, female writers make up over 60% of authors and there is a strong emphasis on the difficulties faced by modern women in a traditional society, whether they be struggles at home, in the workplace or with their partners. The Vegetarian by Han Kang is an early example, and more recent novels like Cho Nam-Joo’s Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 also explore the plight of the individual in society. From writers in Chinese, there has been a lot of fantasy, crime and other genre fiction, with bestsellers such as The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin, The Paper Menagerie by Ken Liu, and The Borrowed by Chan Ho-Kei all sparking a lot of discussion. By contrast, while there are also plenty of translated Taiwanese books in Japan, they tend to cover a multitude of diverse subjects (which can also be said to be one of Taiwan’s specialities) and can be divided into three genres: poetry, literary novels and indigenous literature. Among these, there aren’t many titles which are able to be both literary and popular, to achieve the sales numbers and renown that attract widespread attention.

The edition of Gunzō mentioned above interviewed 70 authors, critics, publishers, academics and cartoonists, asking each of these people from across the industry to suggest one book they recommend translating. There was only one title from a Taiwanese author, Wu Ming-yi’s The Illusionist on the Skywalk. 12 people recommended Korean books, while three recommended books from Mainland China. Over the last two years, Tai-tai Books has worked tirelessly to sell Japanese rights to 16 Taiwanese titles which is almost miraculous, especially given that Taiwanese literature is relatively niche in the Japanese mainstream market. However, there is still a lot of room for future expansion.

Considerations about publishing foreign translations are often dragged down by concerns of localisation and transnationalism. Books by famous authors or with strong “local Taiwanese characteristics” are often seen as the first choice for their portrayal of Taiwanese culture, but for overseas readers this emphasis on setting can serve as a barrier, making it difficult for them to empathise with the story and find it interesting to read. Ideally, the book can attract widespread attention while retaining its local characteristics, and achieve that universality which transcends national borders. Translating so-called “untranslatable” local traits can take more time and energy, often depending on the assistance of editors, reviewers and other translators. In The Illusionist on the Skywalk, the Chunghwa Market and crowded housing communities are shared memories for both Taiwanese and Japanese people, and there should be even more opportunities for boundary-crossing contemporary novels like this going forward.

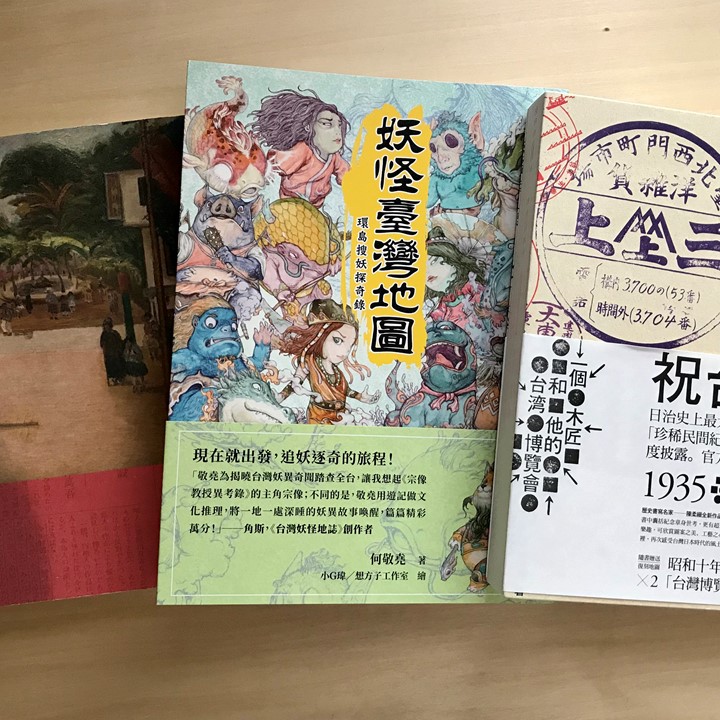

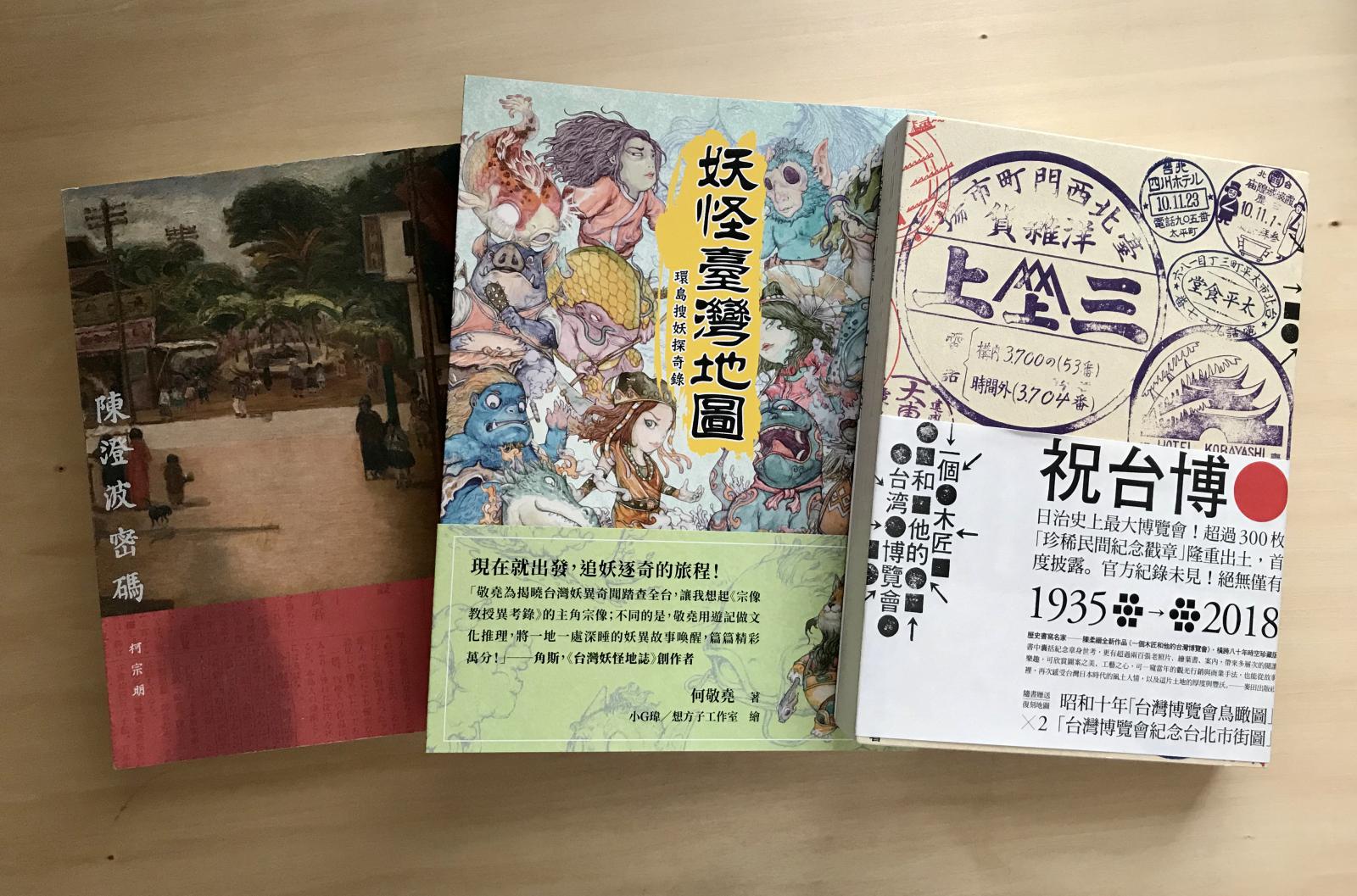

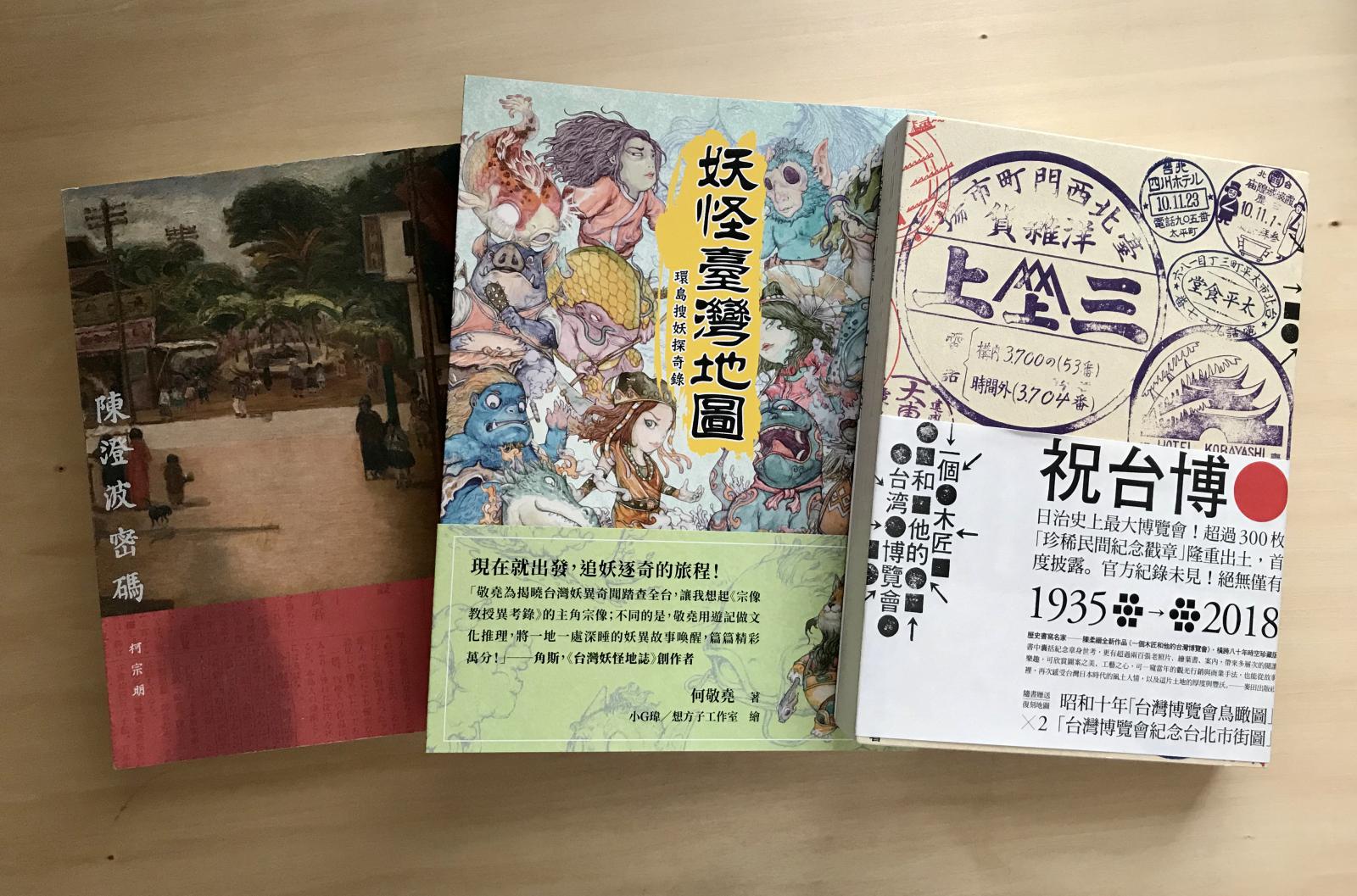

From left: The Tan Ting-pho Code, A Map of Taiwanese Monsters, A Carpenter and His Taiwan Exposition

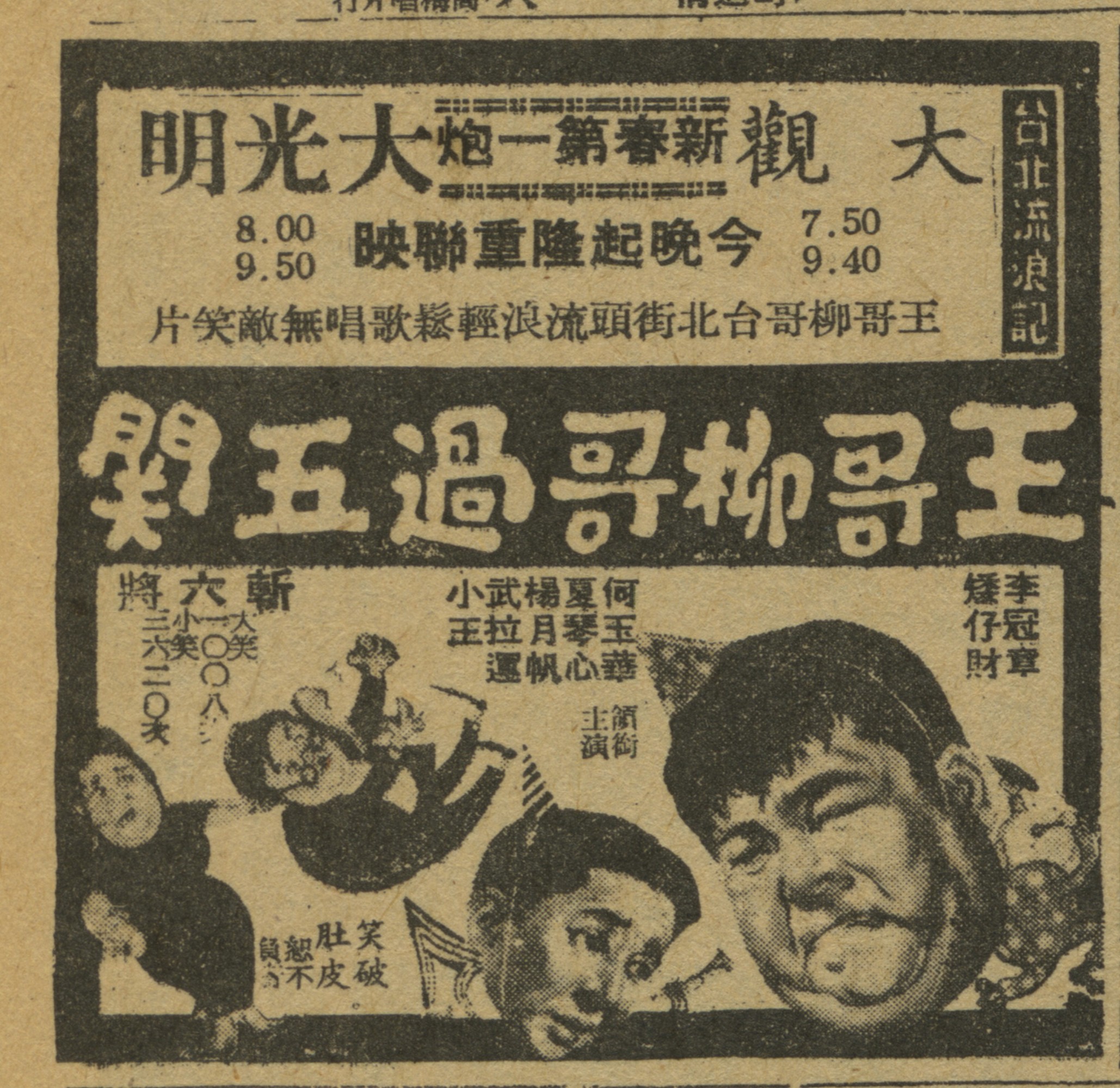

Since Taiwan and Japan are close both geographically and historically, they have a relatively special relationship compared to that of other countries and languages. A lot of books in the last ten years have explored the culture and history of life in Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule (1895-1945). These might initially seem like they would be a good fit to promote in Japan, but Japanese authors have already written a myriad of books on the subject which makes it extremely difficult to make an impact by bringing anything new to the table. Take A Carpenter and His Taiwan Exposition by Chen Ruojin for example, which Tai-tai books was selling the rights to earlier this year. The book is a collection of the three hundred official seals from the Taiwan Exposition which was held in 1935 to commemorate the first forty years of Japanese colonial rule. It is the first time these historic materials have been revealed, attracting historical researchers, collectors and people in design, giving the book a wide range of entry points which has become an important factor for enticing editors. However, we still haven’t signed a contract with a Japanese publisher, the key to making this final sale will be finding a publisher who can produce and sell high-end picture books and hold internal meetings to make accurate print cost calculations.

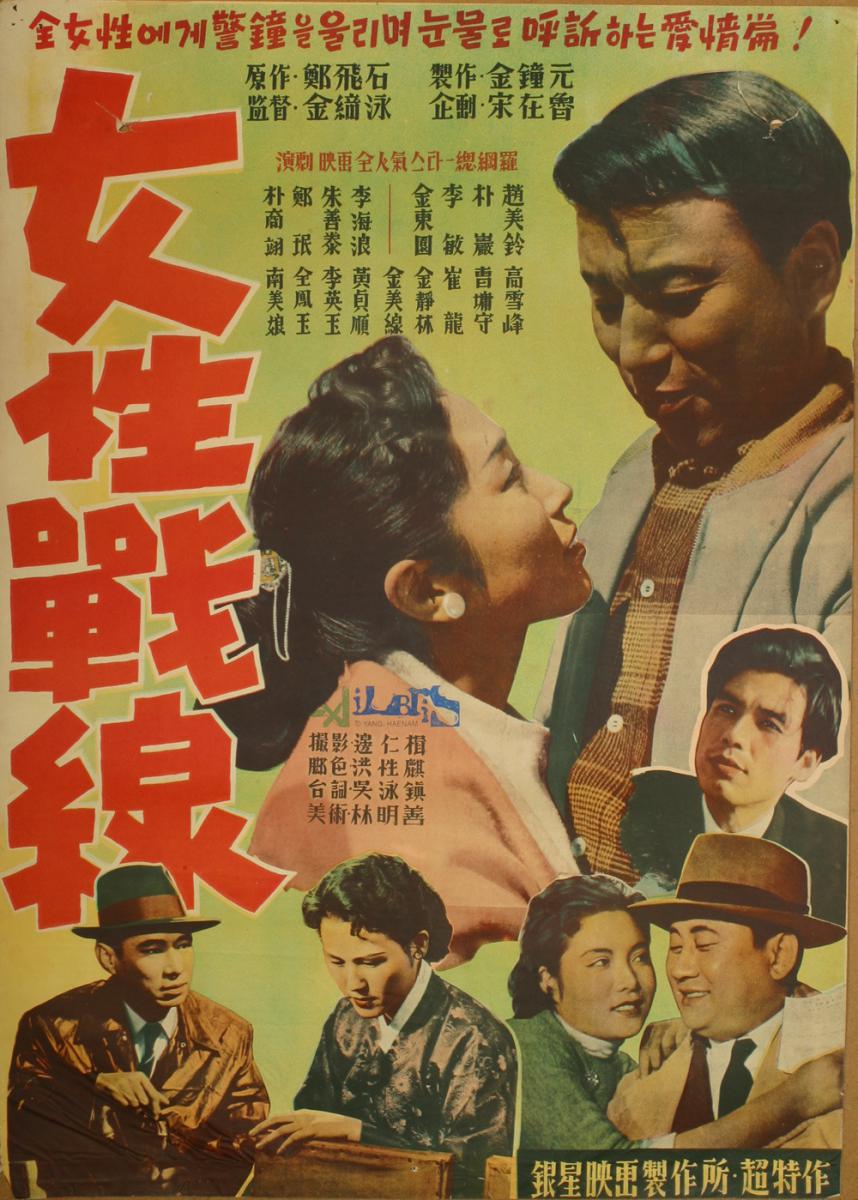

Elsewhere, A Map of Taiwanese Monsters builds on the existing popularity of Japan’s monster trend, while The Tan Ting-pho Code takes a piece of Taiwan and Japan’s shared art history which is unknown to most Japanese people and captures the atmosphere of Taiwanese society after the war but before martial law was declared. These books have potential in Japan but might not be suitable for other countries, this is what makes the Japanese market relatively unique for Taiwanese publishers. From this, we can see the importance of accurately selecting books based on individual markets.

As someone who promotes Chinese-language books in Japan, I am often asked “which books have the best chance of succeeding in Japan?” Regardless of subject-matter, we must return to each book and decide whether it’s enticing and which points or aspects of it will appeal to local readers. It’s best if there are a lot of key elements that different kinds of readers will find moving, and it’s crucial to base recommendations on the editor’s interests and the publisher’s specific direction. As a rule, it tends to be a case of paying attention to Japanese publishing trends and waiting for opportunities, then making a move when the chance arises.

Members of my team at Tai-tai Books do long stays in Tokyo to maintain a stronghold in Japan. In the last few years of going back and forth, there’s been an increase in outstanding Taiwanese writers and books across all genres, prompting Japanese publishers to pay close attention. According to them, however, progressive thinking on the part of Japanese readers might be what is most lacking at present. For example, Taiwan’s legalisation of same-sex marriage last year has prompted discussion of the subject in Japan, just as Japanese LGBTQ fiction exploring gender equality has really started to develop. If we can keep our finger on the pulse, our prospects for the future should look very bright.

.jpg)

.jpg)