I dimly recall in 1982, while I was still in middle school, I once stumbled across a copy of the Taiwanese movie In Our Time in a pile of boisterous Hong Kong movies. It only caught my eye because Lo Ta-yu had a song by the same name. My impression of Taiwanese films at the time was a complete mess. They gave free showings of patriotic movies like Eight Hundred Heroes and Everlasting Glory in the school auditorium, while commercial movies were either about gambling, or they were so-called “social realist dramas”, salacious tales of vengeance populated by gangsters and their molls. Their suggestively eye-catching posters were pasted pell-mell on the blank walls I passed on the way to school. If I mentioned Taiwan films to my elders, they would reply by shaking their heads with derision.

My father would only take me to see foreign films, explaining that they were more “authentic”. On the basis of that single word, I established my cinematic standard. Domestic productions at the time were generally overdubbed in painfully exacting Mandarin, and the image quality was rigid and grainy. The plots were completely disconnected from real life, like watching a stage play. Thus, I readily adopted my father’s view that the higher quality foreign films were the luxury goods of the cinema marketplace.

Later, in the VHS era, video stores were buzzing with word-of-mouth recommendations for Growing Up. I watched it with my brother and found it moving, so we dragged our mother out to see it. She had the ability to become completely emotionally invested in TV dramas, so I was hoping to see if a Taiwanese film could also get her waterworks going. My mother, a woman with zero faith in the domestic film industry, tears streaming down her cheeks, declared, “It’s fantastic! It really tugs at the heart strings!”

As far as I can recall, that was the first Taiwanese movie that felt “authentic” to me. The characters, the story, the way they talked… it all seemed like the sort of thing I observed all around me in daily life.

Years later I was working in the film industry, and had the good fortune to have brief but beneficial encounters with directors like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Wu Nien-jen, and Ko I-chen, and the great film editor Liao Ching-Sung. Just observing the passion and intelligence they brought to their work was an education in itself, to say nothing of the stories and anecdotes I eagerly listened in on. I began to develop a deep admiration for that generation of movie makers. They were a community of idealistic risk-takers, always lending a hand in each other’s projects. Only then, after my curiosity was finally piqued, did I go back and watch all of those movies I had missed out on before (the same movies my friends had told me were “pretty dull” in my younger days). A vague outline of Taiwan cinema began forming in my mind.

I’m not sure if I had simply matured, or if my experiences had changed me, but those movies we all thought were “pretty dull” now seemed to seethe with a subtle power. Even contemporary film makers would have struggled to match their depth of insight. It defies the imagination that these movies made decades ago, often under difficult circumstances, are still being discussed in international film circles today.

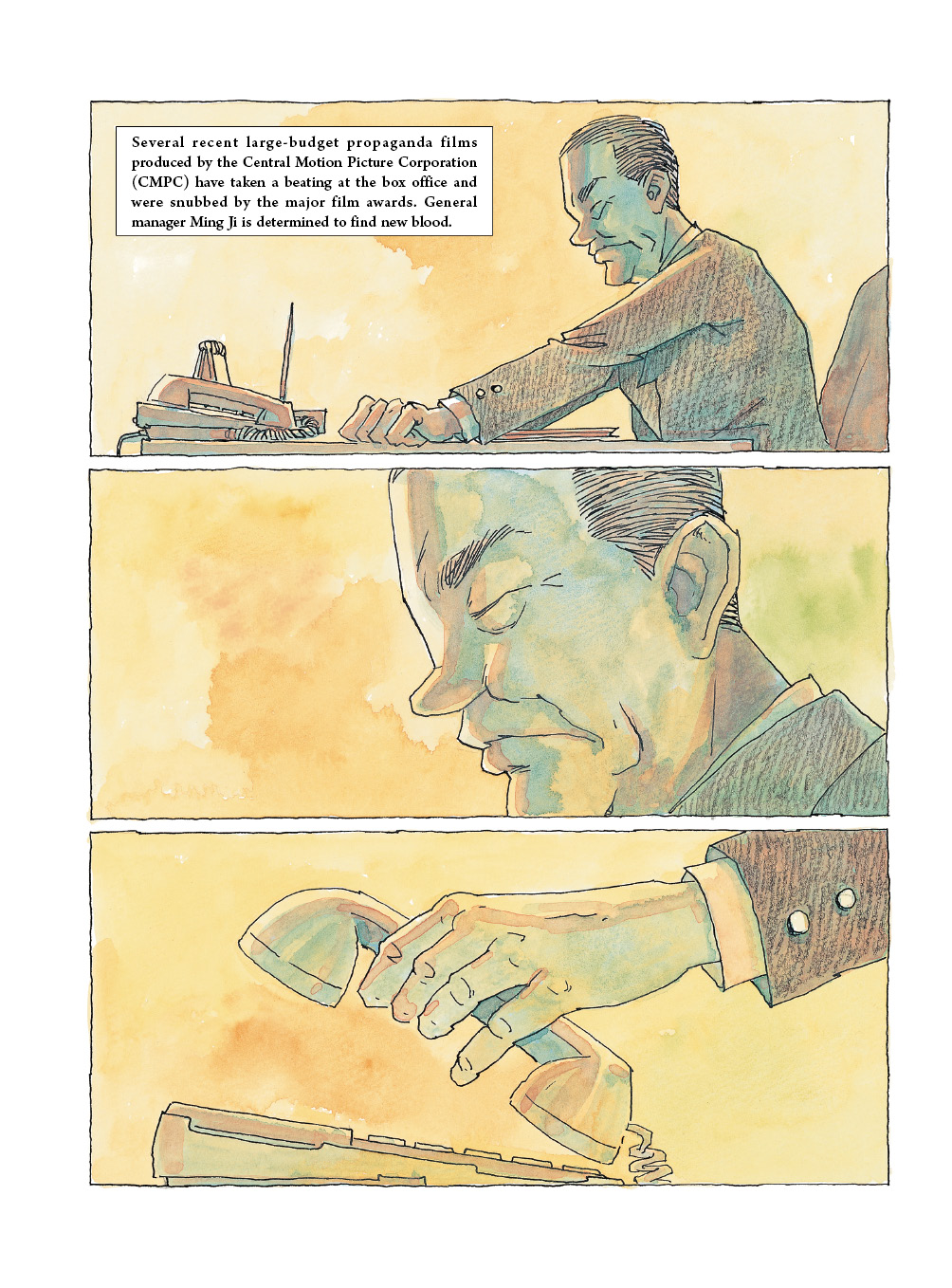

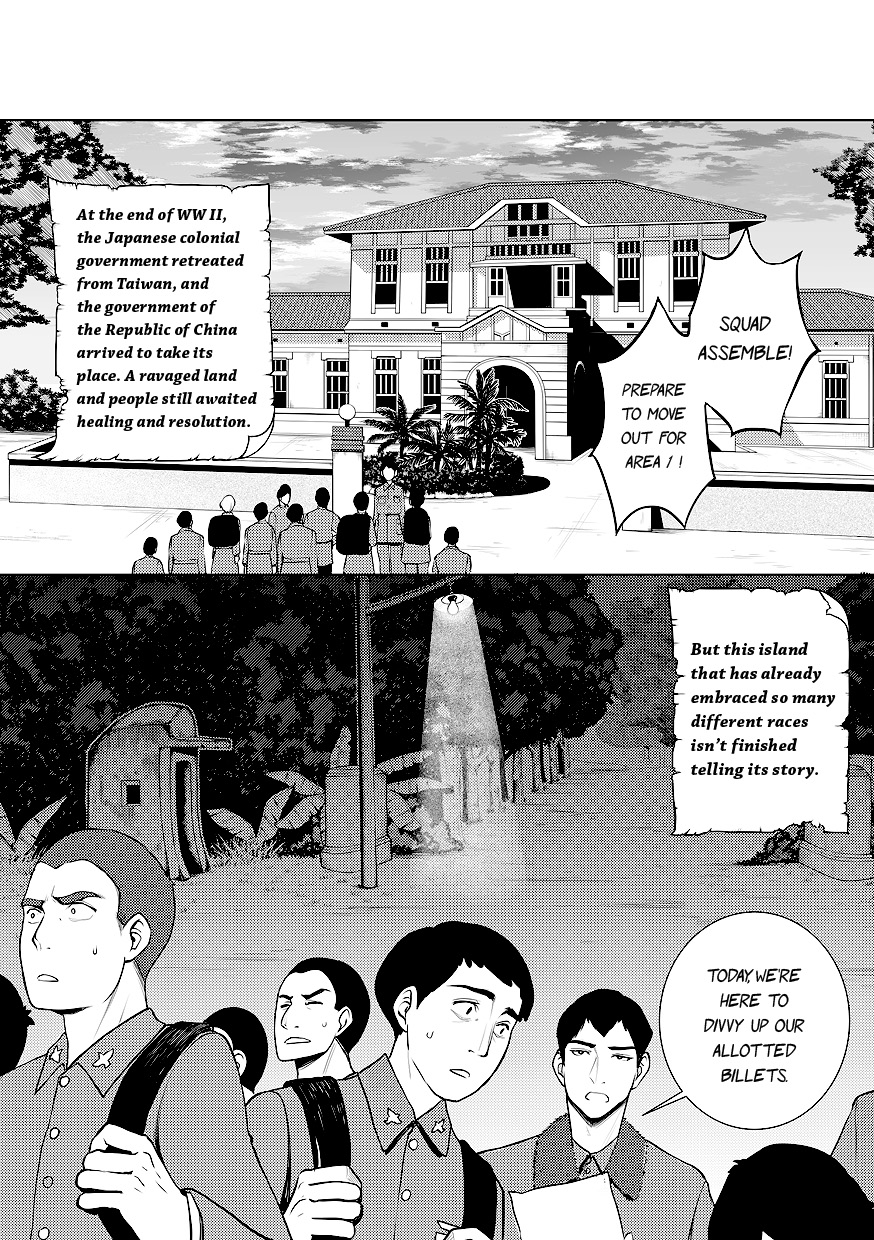

After watching some documentaries and reading about the history of the Taiwan New Wave, I began to understand both the course of its development and its impact. But I was still curious how this group of young movie makers had managed to achieve so much while working within an authoritarian system that discouraged independent thought. With the lifting of martial law still years in the future, many of them had worked directly inside the official media organizations of the KMT, the ruling political party. What were their thoughts in those times? What did they experience?

Years later, as I was flipping through a book by Hsiao Yeh while sitting under a tree waiting for my children’s weekend soccer class, I made a discovery. It turned out Hsiao Yeh had recorded many of his experiences of those times in his books! As I read Hsiao Yeh’s descriptions of those familiar figures, I began thinking: could I draw a graphic novel to retell these stories? Not for the sake of praising movies that had already received ample recognition. Not for the save of celebrating the achievements of those who had long since been recognized as masters of their art. What if I drew this graphic novel solely for the sake of learning and sharing what had happened in those times? What were their thoughts? What had they experienced?