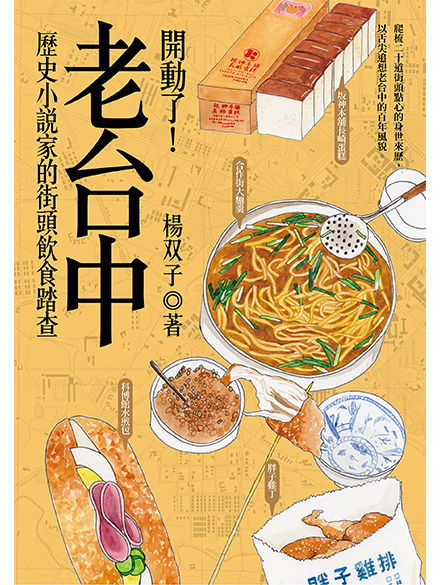

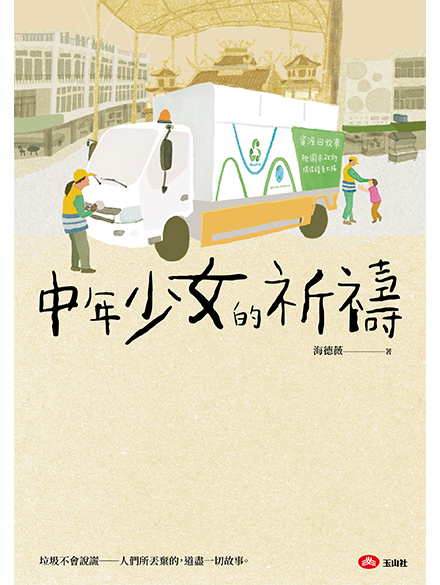

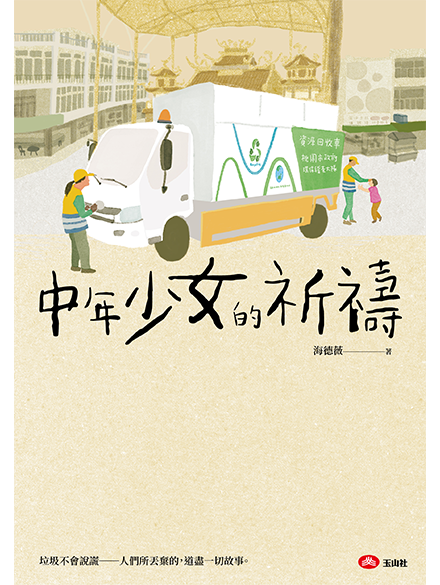

Taiwan’s culinary ethnographers are familiar with older cities and districts such as Wanhua and Dadaocheng in Taipei as well as Tainan City, with its sweet sauces and fresh seafood. Taichung City, situated in central Taiwan and neither particularly old nor remarkably new, presents more of a culinary enigma. What flavors and foods does this city have to offer?

Folk culture enthusiast Yang Shuang-Zi begins this work by imagining the everyday culinary cravings of schoolgirls during the prewar Japanese colonial period before veering off into her own foodie adventures and memories spanning Taichung’s diverse neighborhoods. Eschewing appeals to age, reputation or authenticity, the narrative is inspired instead by the author’s own memories and experiences, imbuing this book with engaging stories and memorable insights.