I first visited Taiwan in 2012, when I was editing the Hong Kong-based Asia Literary Review (ALR). I was encouraged by the enthusiastic literary culture in Taiwan, by the eclectic taste and appetites of Taiwanese readers, and of the open-24-hours phenomenon that is Eslite bookshop/department store/shopping mall—every bibliophile’s dream come true.

In 2014 I visited again not as an editor but as an agent and founder of the Asia Literary Agency, representing Asian authors, experts on Asia and writers living in the region.

After spending several years in London working as an editor of fiction and non-fiction, both in-house and freelance for the likes of the venerable Weidenfeld & Nicolson (an early proponent of literature in translation), Virgin Books, Constable & Robinson and Granta magazine, I moved with my husband to Hong Kong in July 2011. As it turned out, Granta had put in a good word for me with the ALR, who rang up and asked if I’d like to join them as one of their new literary editors: a small team of three. I jumped at the opportunity.

We were a good team: diplomatic, agreeable, and we turned our attention very specifically to what was going on in Asia. Martin Alexander, a poet and our editor-in-chief, commissioned mainly but not exclusively the poetry; my lovely colleague, Kathleen Hwang, a renowned journalist, and I commissioned most of the fiction and non-fiction. And though I had brought a voluminous crate-load of books from the UK, mostly from the Western canon, it sat there, unread, as I became captivated by another time and place.

I wondered why we in the West were not reading more books from writers in the East? Especially now with Asia rising?

We at the ALR had to find out who was writing what and who was published by whom, who was a rising star and who a member of the venerable elite: ‘from the Bosphorous to North Japan’ as Martin put it. So we started making friends, picking up the phone. We had a fabulous launch issue, focused on Korea, both North and South, including an interview with Shin Kyung-Sook, published just before she won the Man Asian Prize for Literature.

Unfortunately, and as these things often happen, the ALR funding was pulled at the end of December 2012, which left us all at unexpected loose ends. But you see, this is where the real fun began…

When the ALR role wrapped up, a few authors approached me separately and completely out of the blue to ask if I’d represent them.

Ah! I thought. Of course!

Like most good agents I have a golden address book full of contacts and after a year of rolling up my sleeves at the ALR I had added pages to that with the many wonderful people I’d met working in the Asia publishing scene. It made sense and felt an entirely natural transition. It seemed as if everything I’d been doing with my life (including my former career as a Korean linguist, my love of introducing people, my ability to happily roll up my sleeves and get on with any job) had been leading me directly to this point.

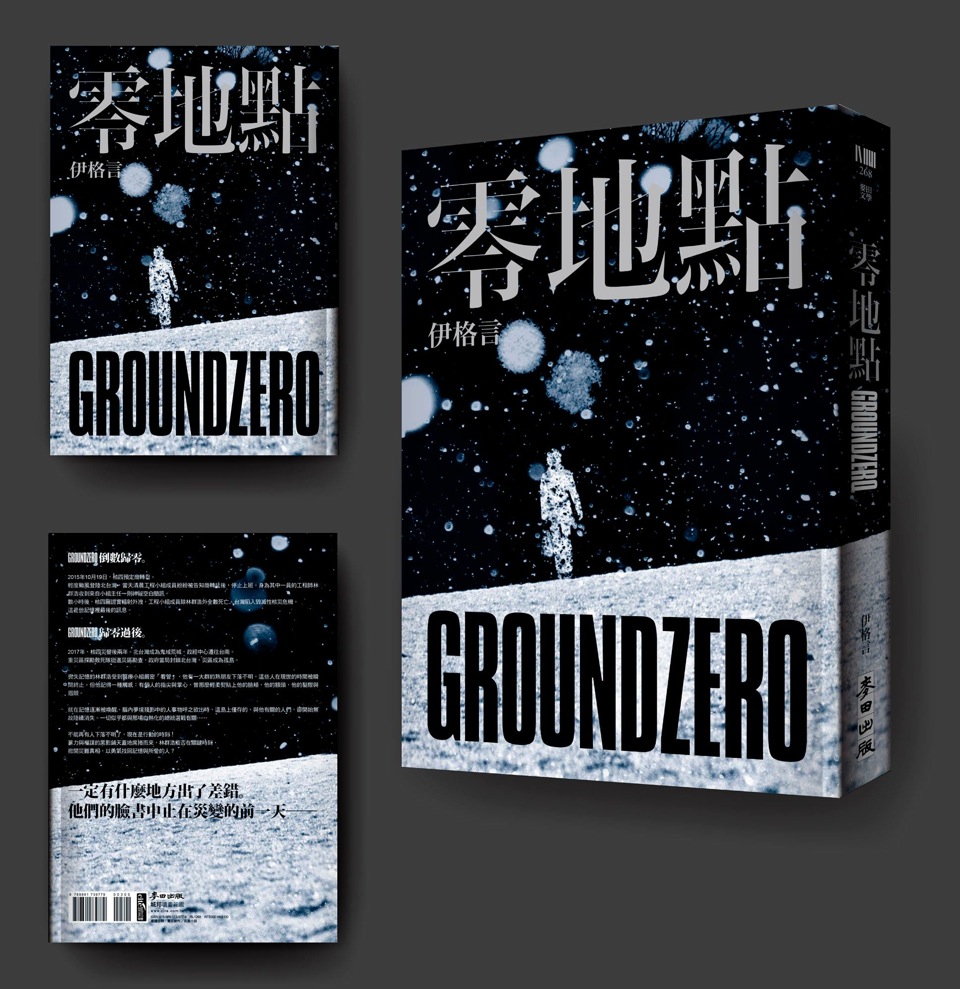

Luckily most of my authors write in English, which means we don’t have to worry about translation as an additional start-up cost. Nevertheless, and as Gray Tan has pointed out, this means that we do compete direct with American, Canadian, Australian and British authors writing in English. I’d qualify that: yes, we do compete, but my authors are writing from a different point of view and we aim to persuade editors and our readers living outside of Asia to look outside the bounds of their own environments and that of the familiar round of names we see again and again on the bookshelves and bestseller lists. Nevertheless, the story and the writing must be interesting enough to stand on its own, regardless of whether it is in translation or not, though it is true that those books that are translated are usually the crème de la crème in their native language or countries and present a very particular and relevant insight into their native socio-economic landscape. They also tend to enhance the English-language market with fresh, new and exciting voices within a particular genre; for example, the crime-thriller HANGING DEVILS by He Jiahong, the John Grisham of China.

One of the greatest strengths and most wonderful things about Asian writers is that their scripts and ideas tend not to be influenced by the Western canon. But the fact is that, generally, readers in the West want to read something familiar, or if it is not familiar they want to be able to see it pyrotechnically multi-dimensionally without thinking they are having a history lesson. To many readers, and unfortunately also to many editors in the West, what’s going on in Asia now, the way people live in Asia now, whatever’s relevant to those of us living in Asia now, may as well be happening in outer space and/or a different dimension. And it is not only just because what Asian authors are writing about proves a challenging sell, but it’s also the way they write. For example, Indian authors, when focusing on their own audiences, tend to write prose that is denser and with a more intricately layered vocabulary than you’ll find in many literary novels published in the UK (perhaps with the notable exception of Will Self). Chinese writers too have a style different to writers in the West, in part shaped by the unique features of their language. So this is where a good translator will come in, influencing the tone and pace so that, while the essence of the story remains in tact, the flow of it becomes something more easily understood by English readers.

One minor challenge about being an agent in Asia, representing Asian writers, is explaining the agent’s role to authors, particularly in China and to some in South Korea, also. These two countries don’t have an agent culture like ours in the West, and the Chinese authors are incredibly wary, if not distrustful, of the term ‘exclusive’ in the agent-author contract. They worry they might lose control, or be taken advantage of. And I’ve found that many authors in South Korea believe that money equals success, in part due to the highly publicised advances achieved by the likes of Shin Kyung-sook, Jang Jin-sung and Hyeonseo Lee. So their initial reaction is that they are not interested in representation unless it means the promise of a lofty advance, that to be given anything less would be shameful. It takes finesse and patience to persuade them that the value of a deal is not only in the money but in the reputation of the publisher and that the value of an English debut can be unquantifiable, leading perhaps to bigger advances, an international profile, eligibility for awards, and/or more deals in other countries. You must understand the myriad social and cultural reasons behind this. With China it is only in part due to their scant regard for copyright, which means that authors are very often taken advantage of, with their works reprinted and sold without their approval; in Korea such regard for money is in part due to their new materialism, coming after years of real hardship and poverty.

What is frustrating to me as an agent and as a voracious reader interested in other cultures, is that the West is still catching up to what’s going on in Asia now. I had three people ask me at Frankfurt last year if I had read FACTORY GIRLS by Leslie T. Chang, as if this brilliant yet eight-year-old book had just been published. Editors still seem to be looking for books about the Cultural Revolution and its consequences and about the dividing of the Korean peninsula, rather than what is happening NOW, when progress has been happening so quickly it’s as if it’s been in light years. The foreign editors wanting me to sell books into the East approach me with titles that are often totally inappropriate: why would the newly urban Chinese have any interest whatsoever in a book about the middle-class, second generation Chinese-American experience in America over the last fifty years?

I would think that, given how China is and has been on an unprecedented upsurge, along with Korea and Taiwan, and how other Asian countries are in the midst of some of the most profound cultural and political changes in their modern history (one only need look at Burma, where censorship was allegedly and only recently lifted), that the West would be desperately wanting to read as much as possible, as quickly as possible, from this region to understand the new world order. Because it is certainly here.

Not every book will work in translation. It is important to find the right books for the right countries and to work with people you trust and like. It’s a long game, and selling a script often takes a huge amount of effort, time and energy. We must all support each other, I think, in this most wonderful endeavour to introduce stories from other parts of the world. It is my hope that we become less and less foreign to each other, so that our stories become more familiar.