Read Previous Part: Translating Taiwanese Science Fiction: Past and Present (I)

In terms of foreign translations of Taiwanese science fiction, the number of translated works remains relatively low and they only tend to be discussed in an academic context. This means it isn’t a market-driven genre so most of the perspectives on it tend to come from within academia and it’s hard for science fiction translators to emerge. For example, take two of the Taiwanese sci-fi translations currently available in English: The City Trilogy by Chang Hsi-kuo and Zero and Other Fictions by Huang Fan. Both are published by Columbia University Press which has a long history of publishing anthologies of Taiwanese literature and were translated by John Balcom who has a close relationship with Taipei Chinese PEN and is also a long-time translator and advocate of Taiwanese literature. Translating works and introducing them to foreign readers generally tends to be quite sporadic and is often out of touch with the mainstream market.

However, it is worth mentioning that the recent rapid developments in Chinese science fiction prompted renowned sci-fi research scholar Mingwei Song(宋明煒) to edit The Reincarnated Giant: An Anthology of Twenty-First-Century Chinese Science Fiction for Columbia University Press in 2018. The anthology included excerpts from works by two Taiwanese authors: a chapter of Daughter by Lou Yi-Chun titled “Science Fiction”, and chapters 5-7 of The Dream Devourer by Egoyan Zheng. Their respective styles definitely stood out among the crowd of Chinese writers.

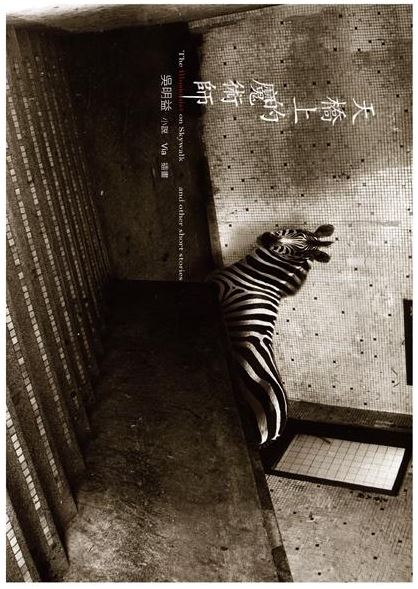

As well as supporters in academia, another important promoter of Taiwanese science fiction in recent years has been the French translator of The Three-Body Problem, Gwennaël Gaffric, who has translated many works including Wu Ming-yi’s The Man with the Compound Eyes, The Illusionist on the Skywalk and Routes in the Dream, as well as War of the Bubbles by Kao Yi-Feng and Membrane by Chi Ta-wei, and in the process he has introduced each work to a French readership.

The Illusionist on the Skywalk

Publishing mediums have also changed dramatically following rapid technological developments in recent years. Taiwanese science fiction has taken advantage of the popularity of e-books and even audiobooks. For example, in 2018 Chang Hsi-kuo’s short story collection Ten Billion Names of the Devil was published first as an e-book and the English edition, also in e-book, will be available online imminently. Isaac Hsu’s long-awaited novel Skin Deep will also be published first in e-book, proving that science fiction writers are staying at the forefront of the times.

While the recent expansion of Taiwanese science fiction overseas might to a certain extent be due to the surging popularity of Chinese sci-fi, what is clear from the examples outlined above is that for Taiwan the genre has developed in a way that encourages considerable diversity, with mainstream writers and sci-fi authors alike consistently publishing works of a high standard. It’s hoped that by including Green Monkey Syndrome by Andrew Yeh and The Puppet’s Tears and Other Stories by Isaac Hsu in the selections here at Books from Taiwan, more readers will get a glimpse of Taiwan’s golden age of science fiction which in turn will promote further translations and development. By reading these classics and considering them in the context of current developments, readers can gain a deep understanding of science fiction’s timeless charm as a genre.