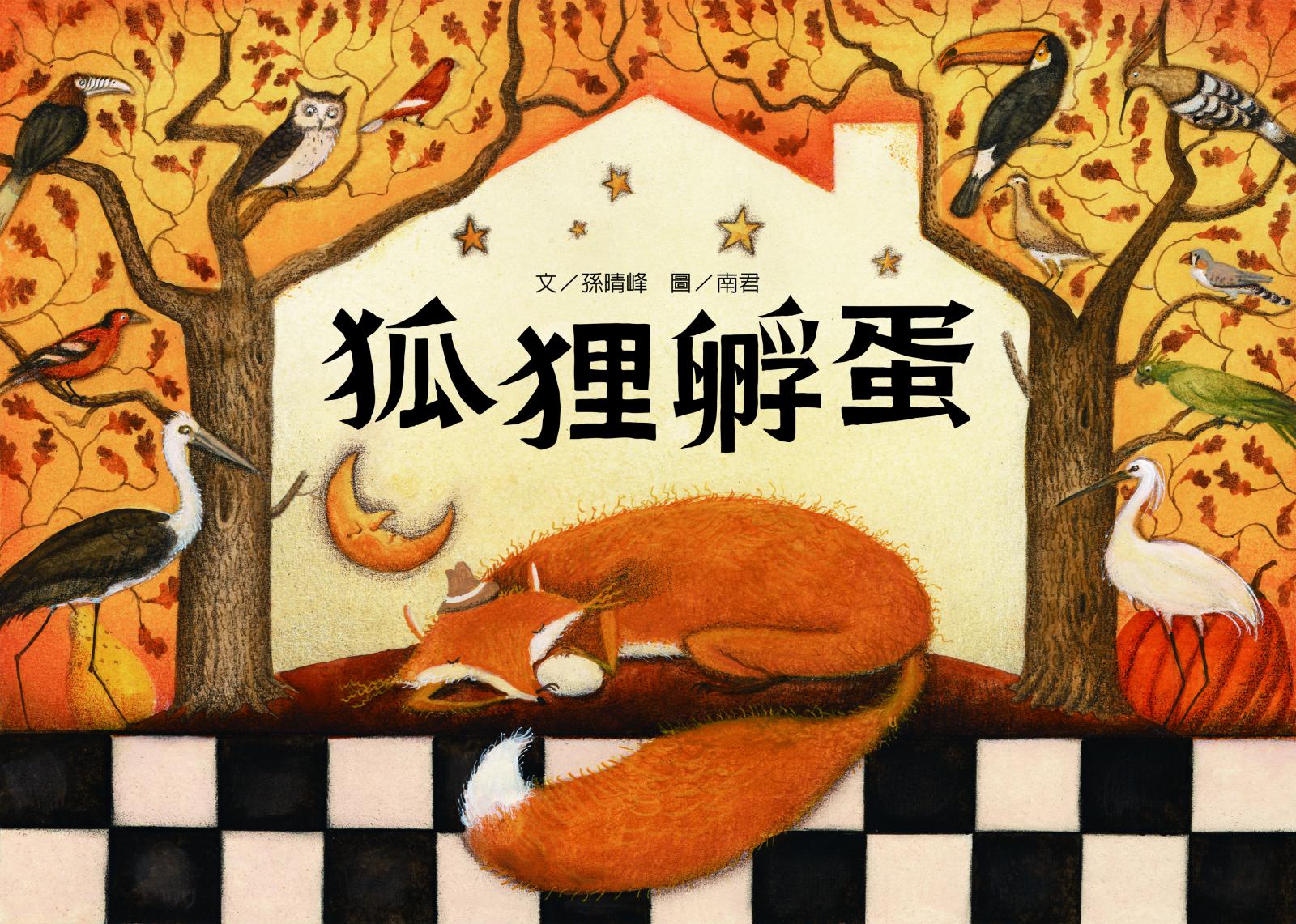

We’ve all read Aesop’s Fables and closed the book with a knowing smile, moved by the love, courage, and humour in the stories. However, many of the fables feature one animal who is never very likable: a solitary fox with sharp fangs who is always labelled as cunning and treacherous. As a lover of fables, children’s book author Sun Chyng-Feng noticed that the fox had been treated “unfairly” over the years and decided to write Fox Hatches an Egg to gently invert the role.

Reversing the Character’s Image and Shaping Its Ideal Values

In the interview with Sun Chyng-Feng, we started by discussing the fox’s traditional role as a villain. She talked about how she started writing fairy tales in her third year of university and how she wanted to subvert the traditional way of thinking by challenging the various stereotypes surrounding widely-held gender and class distinctions. As topics like these are very important to her, Sun Chyng-Feng’s typical creative process is to start by deciding on the story’s main notion or subject matter, and then running with a story to express it. For example, Fox Hatches an Egg discusses the process of transforming from “selfish” to “selfless”.

Since Sun Chyng-Feng has lived in the US for many years, collaborating with illustrator Nan Jun on Fox Hatches an Egg was more like a relay race than co-creation. First, Sun Chyng-Feng completed the manuscript and then Nan Jun came up with the image concepts and drew the illustrations. This process gave both author and illustrator the most space for creativity. Talking about the content of the illustrations, Sun Chyng-Feng said there was one image which left a particularly deep impression on her: a white duck egg which takes up almost an entire page. This simple, bold composition captures that moment when Fox suddenly sees the duck egg in the undergrowth and he’s so excited that everything else in his mind goes blank, as if the egg takes up the entire universe.

Love Between Species and the Warm Life of Companionship

For illustrator Nan Jun, the most moving part of the story was the cross-species friendship between Fox and the duck which was brought about by chance but eventually became inevitable. He recalls his own childhood home where his kind-hearted father would sometimes look after stray animals and even adopted piglets, ducklings, and other unusual “pets” by modern day standards. When reading Fox Hatches an Egg he could completely understand how after Fox and duck kept each other company, Fox can no longer see the duck as food and instead feels a wave of affection towards it.

This is why when we asked Nan Jun which image was his favourite, he immediately said the cover: a picture of Fox curled up around the egg and sleeping soundly, with the two characters framed by the shape of a house. Nan Jun admits that the painting process means that you can’t always capture one hundred percent of the scene you imagined, but once he saw the completed cover he felt it had come out even better than he could have hoped. It really captured the warmth between Fox and the duck.

In addition to the subtly revealed affection between the two characters, Nan Jun set the book during autumn and meticulously planned the detailed settings. “The special thing about setting it during autumn was that even though the weather would be cold, the pictures would be filled with the kind of colours which would make readers feel that sense of warmth.” He added that this all tied back in with the feelings between Fox and the duck.

True Feelings Can Transcend Languages and Borders

At the end of the interview, we chatted about the potential for Fox Hatches an Egg to reach an international readership and Nan Jun stated he was particularly confident in the book’s portrayal of the closeness between the characters: “Fox Hatches an Egg will resonate easily with people of all ages and races because emotions are a universal language. It’s a book you can fall in love with as soon as you read it.”

Sun Chyng-Feng also believes that the book tells a universal story about love, and that there are no specific cultural or geographical limitations to it. In the end, Fox is so upset by his actions that he becomes a vegetarian and is more than happy to make that sacrifice. These bittersweet sentiments are what makes this the perfect fable, and also bring a touch of real emotion to the story. This may be why the book resonates so much with readers.

.jpg)