Read Previous Part: Taiwanese Crime Fiction: Analysing How It’s Read, Written and Published (I)

In 1988, Lin Fo’er, the publisher of Mystery Magazine and founder of Lin Bai Publishing House (as well as a writer and poet in his own right), launched the Lin Fo’er Mystery Award. Even though it only ran for four years, it was still the first ever Taiwanese literature prize specifically for short stories in crime writing. In the same spirit, the Taiwan Detective Club was founded in 2002 (renamed the Mystery Writers of Taiwan in 2008) and in 2003 launched the Mystery Writers of Taiwan Award, which similarly encourages and nurtures potential in up-and-coming short story writers of crime fiction. Authors who have started their careers here include Mr Pets, Wen Han and Chan Ho-Kei, the latter of whom has gone on to sell international rights in many territories, his full-length novel The Borrowed has sold rights in more countries than any other Chinese-language crime novel to date.

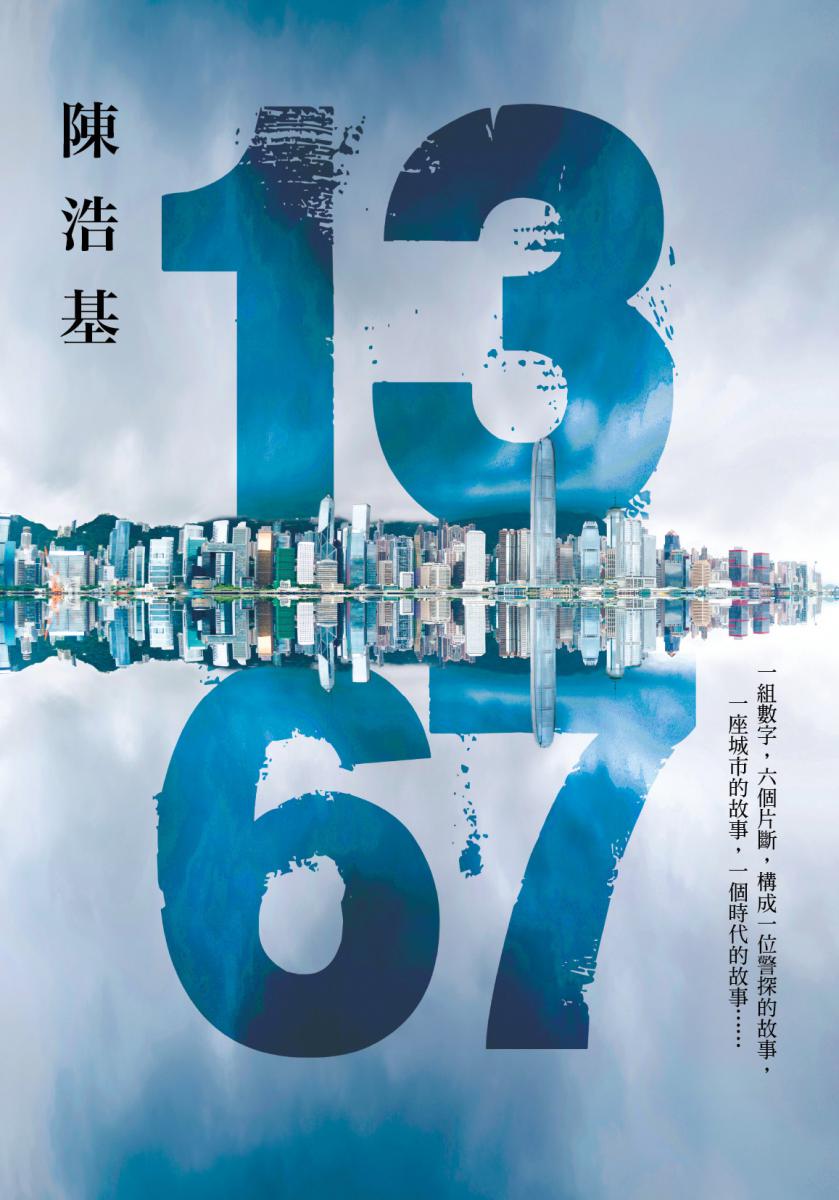

The Borrowed

The Soji Shimada Mystery Award was established in 2008 and is awarded to debut crime writers for full-length novels. The most recent winner was Tang Chia-Bang for The Wild Ball Club Incident in 2019. A penetrating portrayal of Taiwan, it blends history, railways and national baseball and has received interest from publishers in Korea and Japan. Publishers are also committed to developing new talent, for example Apex Press published Chopsticks, a short story collection of suspense crime with a supernatural slant, by five authors from Taiwan, Japan and Hong Kong. Sharp Point Press encourages authors to combine crime and folklore in light novels such as My Sister Is A Teenage Bone Collector 1: Never Say Die, as a reflection of the younger generation’s abundant enthusiasm for diverse works which push boundaries and explore new subject-matters.

After absorbing so many creative elements of crime fiction from Japan and the West, Taiwanese authors initially found themselves overemphasising plot twists, or conspicuously playing into detective stereotypes, or over-researching societal issues. This mere imitation of the genre alienated Taiwanese readers. However, during the process of steadily internalising the components of crime fiction, authors began to realise that Taiwan’s distinctive history and geography generated a complexity and inclusivity which resonated with local readers, and gave it a niche in international markets. The latest manifestation of Taiwanese crime fiction today usurps cold-blooded violence with strong emotional ties, it seeks a to portray an honest and original perspective on crime and human nature, thus drawing up its own classification for itself bit by bit.

In recent years, the Taiwanese government has been collaborating with production studios on developing key cultural projects for film and television, with several crime titles on the list. In addition to these original adaptations (such as the recent Netflix series The Victim’s Game), it will be worth watching to see whether this developmental collaboration between authors, publishers and production studios will bring with it any new impacts or growth for Taiwan’s entire cultural ecosystem.