This graphic novel was published in conjunction with the Taiwan Film Institute. Could you describe the process of collaboration? How was the subject of the book decided? How were the historical materials gathered? And how did you organize these materials to create a compelling storyline?

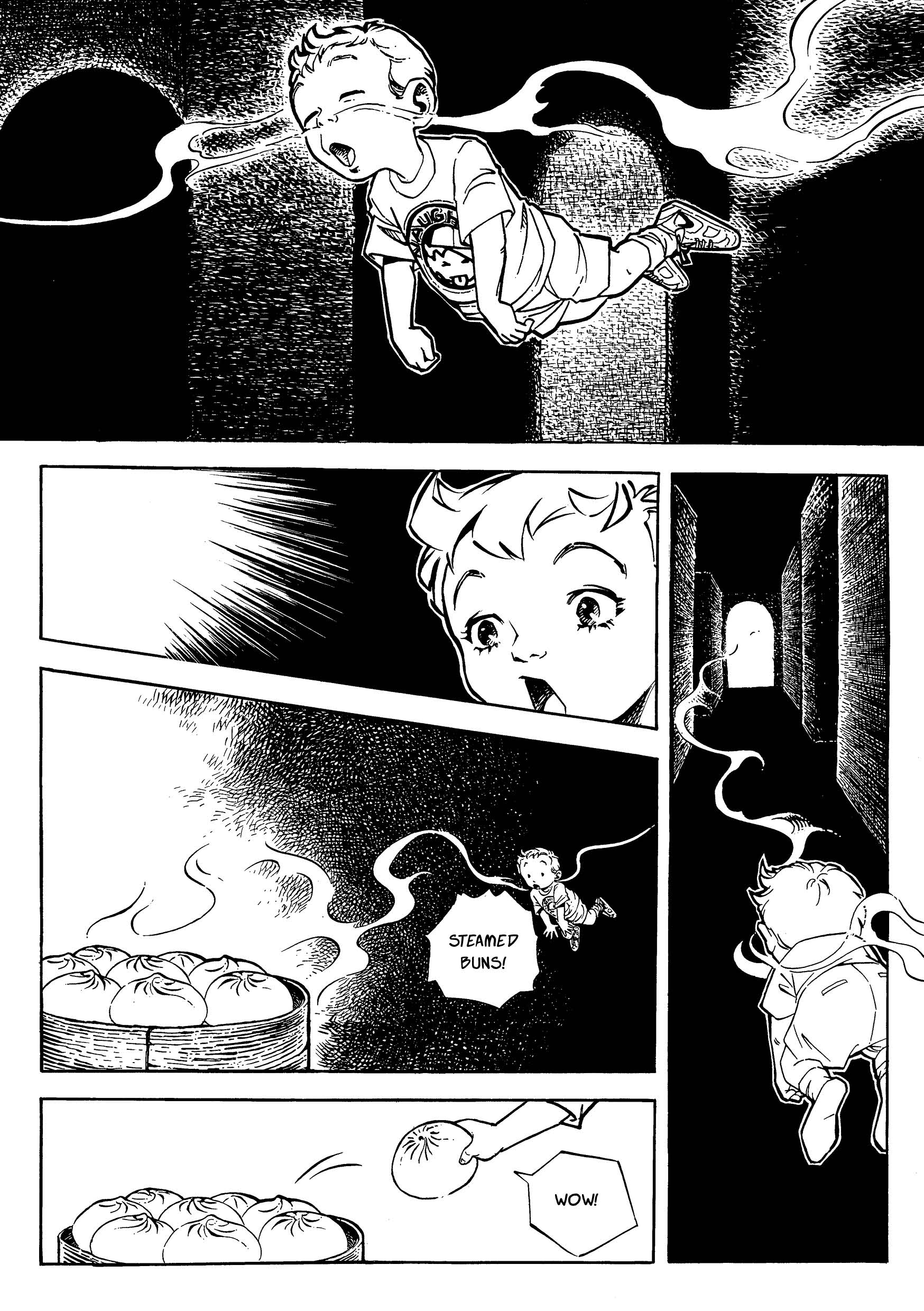

Actually, it was a very open process. The institute has a large historical archive – film, newspapers, data on actors and movie industry workers, old equipment – pretty much every kind of historical material from the post-war period. It’s a treasure trove. They gave me full rein to choose whatever topic I wanted. The bygone studio back lots setting of the first volume was meant to draw attention to the core work of the institute – film restoration – since this was our first collaboration.

Film restoration requires a lot of technical knowledge, but (I focused on) the why of it. What makes these old films so important that we need to restore them? If readers don’t understand the lost era of Taiwanese-language cinema, if we can’t generate an emotional connection to these films, they will lose their significance. Then who cares whether they are restored? So the story had to help readers understand the 1960s golden era of Taiwanese cinema. Just setting this premise was already a huge undertaking. I had to acquire a thorough knowledge of the filmmaking process of the era – cinematography, lighting, printing, tracking… Only with this knowledge could I understand the difficulties faced by filmmakers of the time. What were the post-production costs? Why were budgets so limited? Only then could I depict the passion of these characters who persisted in making movies despite living in an era of such limited resources. I hope readers will feel that passion, and perhaps better understand why we should treasure these films. Then maybe they can appreciate why it is such a precious opportunity to see them shown again on the big screen.

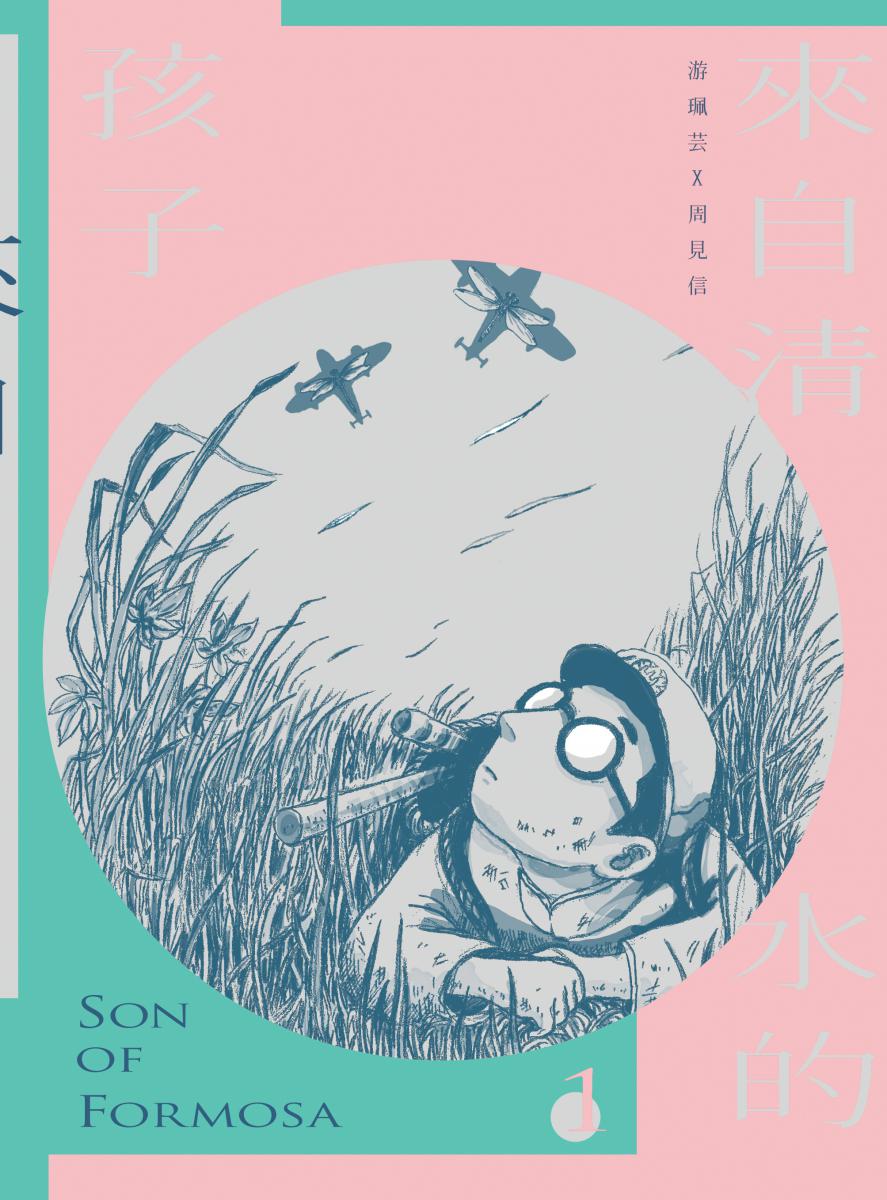

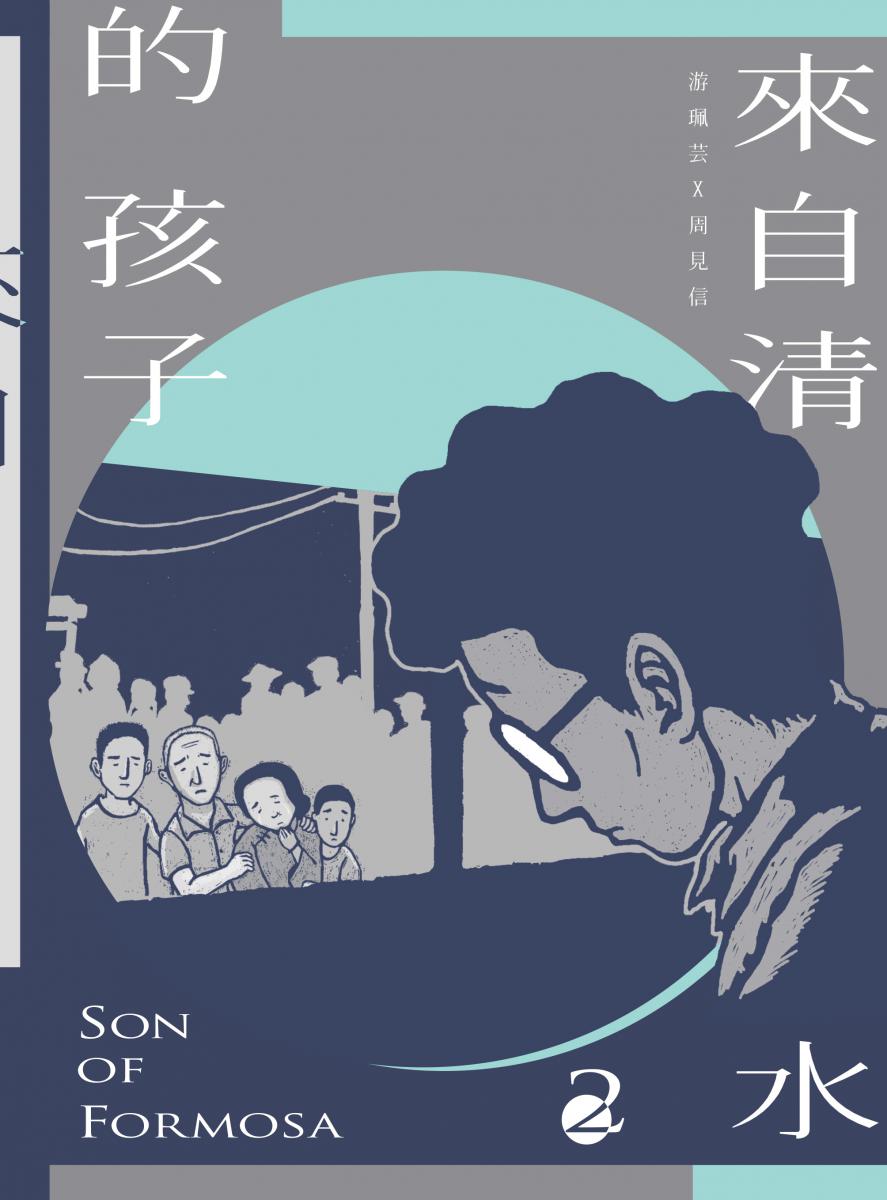

Your previous book focused on the subject of film restoration. The current one focuses on the art of hand painted film posters and billboards. Are there any interesting anecdotes you can share from the process of developing these graphic novels?

While drawing the previous book I accompanied the Taiwan Film Institute team on a trip to Taichung to better understand the film restoration process. We went to a warehouse on the outskirts of the city, where, along with a bunch of other junk, there were these neat stacks of film canisters. The family of the warehouse owner once ran a business showing open air movies in the squares in front of local temples. That’s why all of this stuff was there.

The team carried out all these dusty canisters and stacked them in their truck one by one – it was hard physical labor! I thought about everything that would happen next – each would have to be carefully inspected back at the archives and ones that were too badly decayed would be thrown out – so much work. But somewhere in that stack of canisters they might find a lost film. The work of saving old films is so labor intensive, and sometimes you find nothing at all. It’s a bit like panning for gold. But it is still necessary.

While I was collecting material for the second book, I came across an interesting fact: sometimes the people painting the posters didn’t know what would be in the movie! Because there was a mad rush to produce these Taiwanese-language films, sometimes studios ran short of cash, so they would go to the movie theaters begging for capital. The movie theaters needed to show movies to make money, and generally the movies would be profitable as long as they controlled costs. So the theaters would agree to invest, but they needed some kind of guarantee that the studio would actually complete the film. The movie poster was the guarantee. The studio would take photos of their actors and some preliminary plot sketches to the poster artists, and from this limited information they would have to create a poster as if the movie already existed. The studios could then take the poster to the movie theater to request funding. To me, this was a really interesting way of doing things.

.jpg)

We’ve heard that the character of the painter in the book is derived from Chen Tzu-Fu, an famous painter of movie posters from the period. How much of the original Chen Tzu-Fu remained once you were finished molding the character? Why did you retain these parts of Chen Tzu-Fu’s life?

Two painters, Chen Tzu-fu and Juan Ta-yung, supplied elements of the character, though I took greater inspiration from Chen Tzu-fu. Because Chen Tzu-fu was recruited into the Japanese army, and because at the time I was reading Wu Ming-Yi’s The Stolen Bicycle which talks about the experiences of Taiwanese soldiers in Southeast Asia, I started to form this image of a macho, tough-guy sort of painter. Since he lost his arm in the war, the image also became associated with the character of Yang Guo from Legends of the Condor Heroes, and that set the form of the character.

.jpg)

What’s your impression of Taiwan’s hand-painted movie posters? Can you share with our readers your favorite poster?

The beauty of hand-painted movie posters can’t be captured in reproductions. The way the text and images are arranged reveal a lot about the careful thought that went into compositions, as well as each artist’s individual style. You can spend a lot of time just admiring this aspect of the art form.

There are so many that I like, but I’ll share a bit about one from the movie Son which left a deep impression. You see three siblings on the train tracks. The son is blind. The middle sister is mute, and oldest sister leans on the middle sister because she can barely stand. Behind them, you can see the train hurtling towards them. From this image you can get a sense of the tragic character of so many Taiwanese-language films. You break out in a cold sweat seeing what could happen to the three siblings. I think this is a classic example of a poster that can stir the viewer’s curiosity about the movie.

A number of movie posters make appearances throughout the course of the graphic novel. Is there one that you particularly liked? Can you tell us why?

My favorite is probably the poster for Heaven and Earth Sword, an wuxia, or martial-arts adventure film. Chen Tzu-fu had a lot of experience painting wuxia posters. He once said painting wuxia posters was second nature to him, and it really shows in his compositions and technique. I wanted to draw something like one of his posters, so for me it was a pleasure to envision this poster and draw it into the graphic novel.

Read more:

- Jian Jia-Cheng: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/authors_info.php?id=93

- The Movie Painter: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/books_info.php?id=383

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)