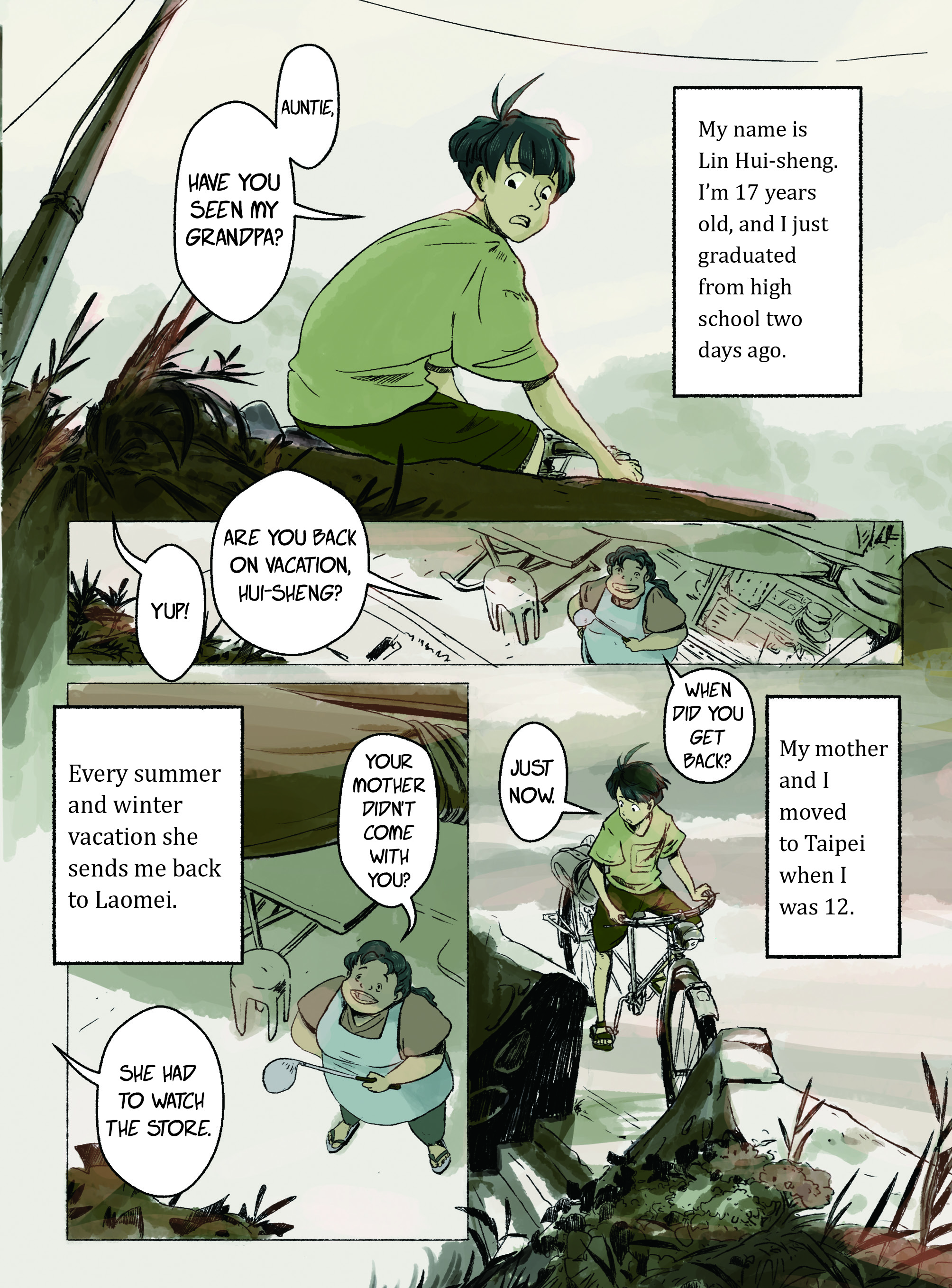

Becoming Bunun is a coming-of-age story by acclaimed Taiwanese novelist Kan Yao-Ming, widely regarded as the pioneer of neo-nativist Taiwanese literature. Set in the aftermath of World War II, Becoming Bunun revolves around Halmut, a young man from the Bunun tribe, whose dream of playing professional baseball with his childhood friend Hainunan is dashed when the latter is killed during an American air raid (the two boys are more than just friends, though their forbidden and unrequited love ends in tragedy). The book is heavily inspired by the Sancha Mountain Incident of September 1945 – during which an American bomber carrying newly-liberated prisoners of war crashed into Hualien County. In Kan’s fictional retelling of the incident, Halmut is part of the rescue team that searches the mountain for survivors. While doing so, he finds an American pilot alive but hesitates to save his life, still grieving Hainunan’s death at the hands of American troops. The moral quandary Halmut confronts and ultimately resolves is part of what makes Becoming Bunun a classic bildungsroman, a journey of self-discovery and personal reckoning.

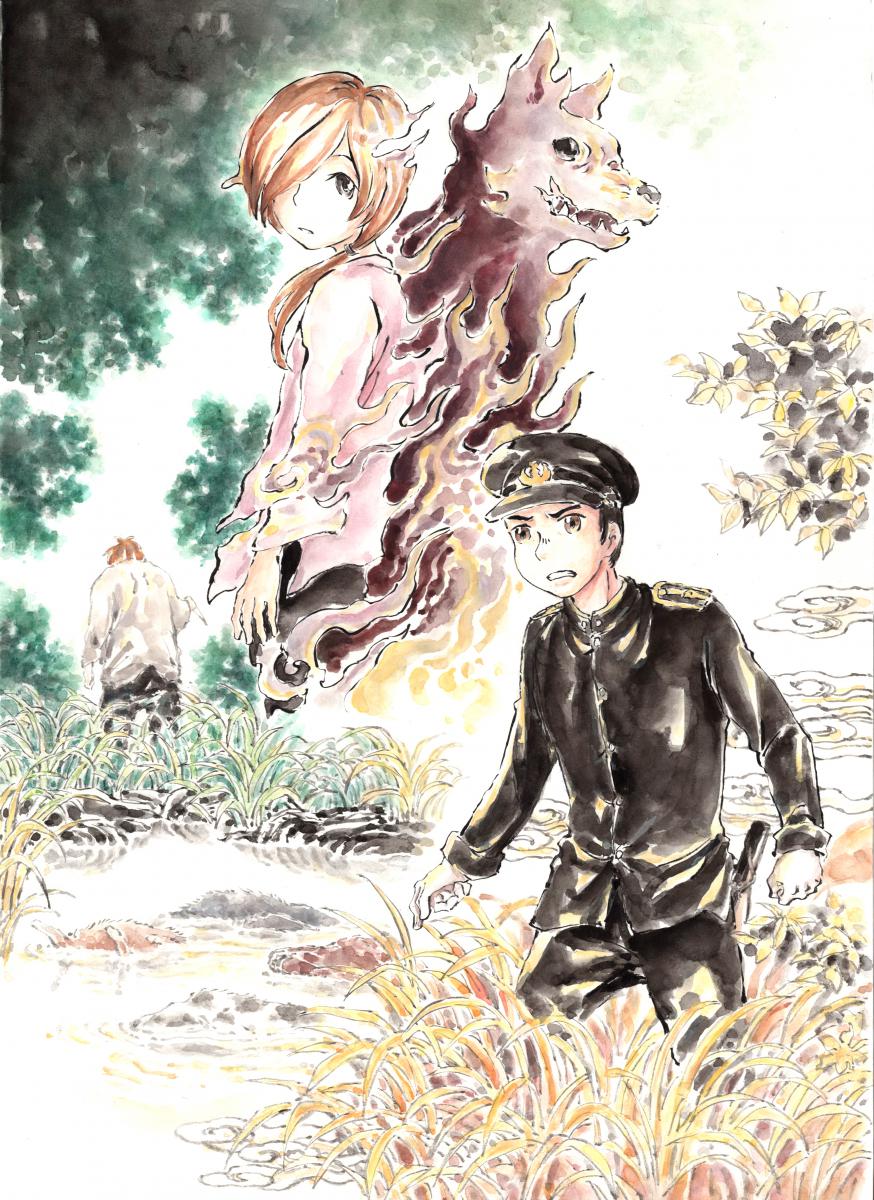

The novel takes its name from the Bunun language (the original title “minBunun” means “to be a Bunun”), which feels particularly fitting as Kan draws from Bunun heritage and culture throughout. The folklore and rich, mythological imagery Kan weaves throughout the story inform our reading of the text, deepening the novel’s exploration of man’s relationship with nature and Indigenous beliefs. Kan is a writer known for his historical fiction, and Becoming Bunun is no exception; throughout the book, he turns his attention to Taiwanese history and the real lived experiences of Taiwanese people, outlining the local tensions during and after the Japanese occupation, the challenges of healing from post-war trauma, and the barriers queer folks faced during a time when same-sex relationships were stigmatized – Halmut and Hainuan’s short-lived and unreconciled relationship is tender though ill-fated, extending the magnitude of Halmut’s grief.

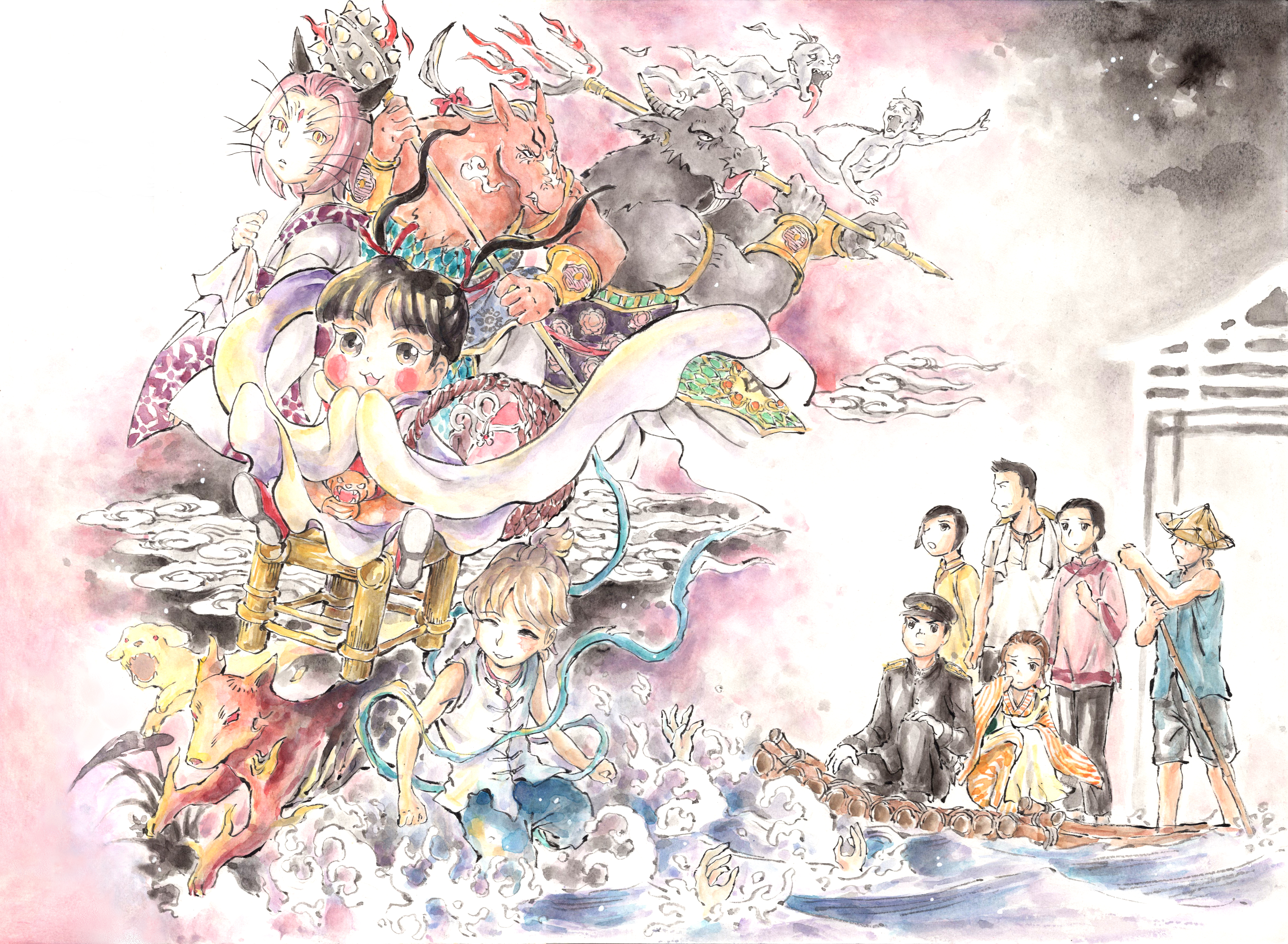

By creating space to explore Taiwanese history and its kaleidoscope of different identities, Becoming Bunun also amplifies the stories of Taiwanese residents during and after World War II, giving voice to narratives that may have been sidelined in the global theater of operations. Every character, no matter how minor, is brought to life with vivid detail – from the powerful hundred-step snake river, personified through Kan’s imagination in a way that makes Taiwan’s topology itself a core part of the story; to the sambar deer he encounters at a cathartic moment towards the end of the novel, which he believes to be the “Deer King” from Bunun legend; to the clouded leopard he sees as himself in a dream, an instance of the importance that Bunun culture places on divining the future through dream interpretation.

Becoming Bunun is many stories within a single novel, as Kan brings different genres (historical fiction, bildungsroman, poetry, elegy) and even languages (Bunun, Chinese, Japanese, English) together to tell a broader story about love, mourning, and self-understanding. Suffused with suspense, heartbreak, and loss, Becoming Bunun is a window into a lesser-known chapter of Taiwanese history, intertwined as it is with deadliest and most destructive war to ever take place. Rooted in Bunun culture yet universal in its exploration of grief and desire, Becoming Bunun is a timely reminder that diverse traditions and beliefs are worth protecting; and a powerful testament to the way storytelling allows the people we care about to live on in personal and collective memory.

Read more:

- Kan Yao-Ming: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/authors_info.php?id=49

- Becoming Bunun: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/books_info.php?id=410

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)