It is clear from Liu Ching-Yen’s previous works that he has a specific fondness for character-driven narratives, which he says derives from his background in journalism. Interviewing people and finding out their stories was a daily exercise for Liu as a reporter and he developed a particular passion for human-interest stories.

A Boy as the Black Swan

Liu based the story of I Am the Black Swan on three people he had encountered. The first was a teenaged boy he met in church who was dancing one of the lead roles in his high school’s production of Swan Lake. Next was a young girl who Liu met while hosting his children’s TV show My Reading Bakery. She studied ballet and her passion for dance was immediately evident in every moment of her life. Lastly, during his university days Liu had interviewed the famous Taiwanese dancer and choreographer Lin Hwai-min, as well as Lin’s roommate at the time who’d said: “If you see someone leaping instead of walking down the street, that’s Lin Hwai-min.”

Thus, Liu tied the figure of Lin Hwai-min together with the story of the boy who danced the Black Swan and the little girl who loved to dance so much she skipped across the street, to create a narrative about gender roles, pursuing your dreams and how art merges with life.

Connecting with the Stirring Topic of Gender

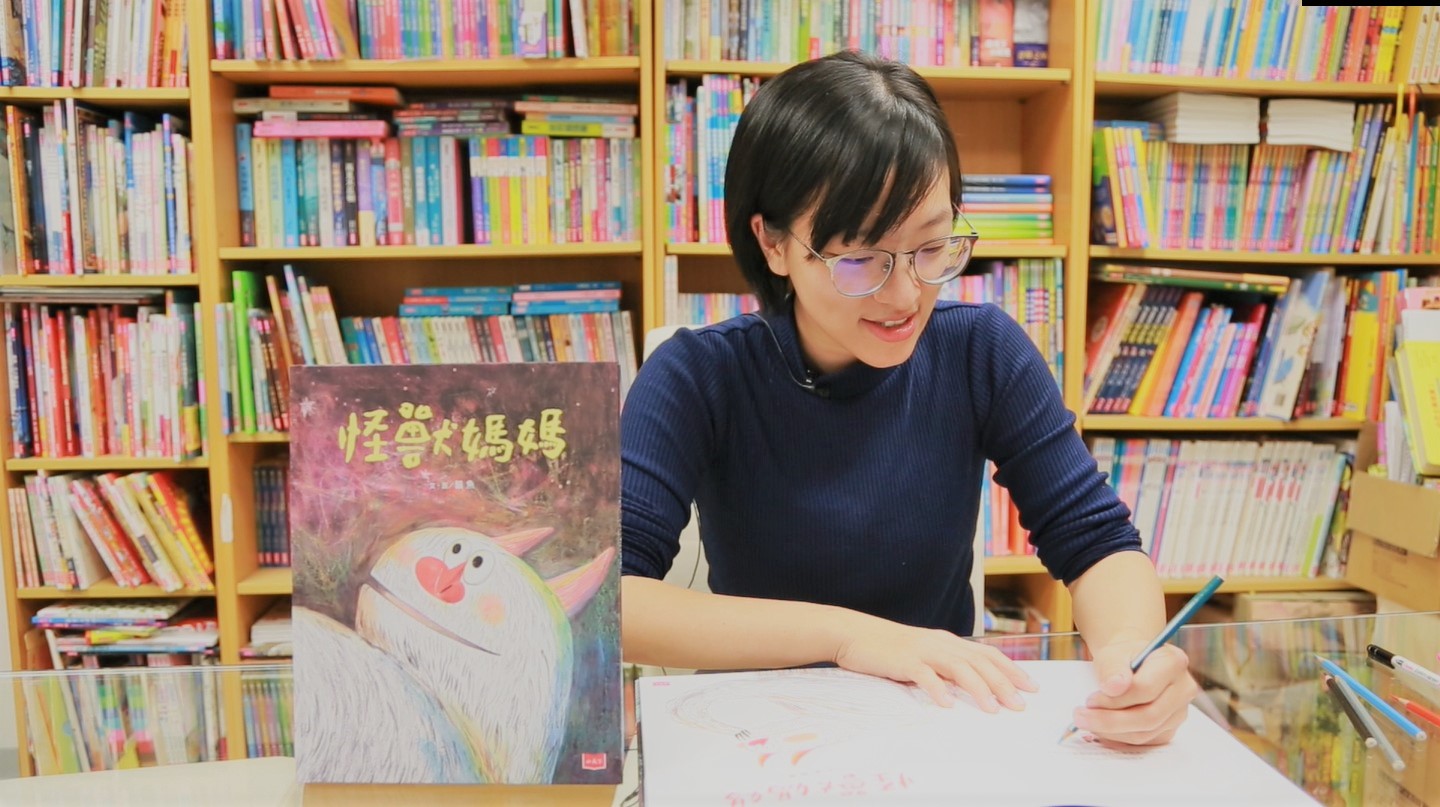

When she first read I Am the Black Swan, illustrator Chang Pei-Yu said she was immediately drawn to the part on gender roles. She remembered her own childhood experience of being forced to use a pink schoolbag even though she really liked the color blue. Later, when she studied early German literature at university, she realized that the field was solely occupied by male writers. In I Am the Black Swan, she was particularly interested in Amin’s character and was extremely curious about how gender roles would be handled in a children’s book.

.jpg)

Naturally Curly Hair and a Red Dance Costume

When Chang contemplated how to lay the groundwork for Amin as a character, she kept debating whether to emphasize his artistic nature and make him stand out from the crowd, or to depict him as an ordinary child. She also felt that Amin’s slight rebelliousness and stubborn perseverance were typical childhood traits. In the end, she decided to do a combination of the two: she gave Amin naturally conspicuous curly hair but a very simple dance costume to show the side of him that is just an ordinary child.

However, when it came to the color of his clothes, Chang decided to use bright red to represent Amin’s inner-life and to show his strength. This red appears constantly throughout the illustrations and is crucial to the book. Finally, Chang decided to use a combination of colored pencils and collage which she hoped would convey the effortless feeling of agility that comes with dancing.

Chang and Liu’s Key Hopes for the Reader

Chang says she hopes readers will enjoy the simple pleasure of the illustrations and that children will get a sense of the more relaxed, happy side of art. She hopes that the dynamic artwork will let children experience the movement and rhythm of dance and gain a sense of its beauty.

Liu hopes that children can understand: “No matter what your parents demand that you learn, the most important thing is that you know whether or not you like it, because you are going to need passion if you want to master it. You can do anything you want regardless of gender, but you must embrace it and pursue it with a burning passion.”

Read more:

- Liu Ching-Yen: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/authors_info.php?id=30

- Chang Pei-Yu: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/authors_info.php?id=359

- I Am the Black Swan: https://booksfromtaiwan.tw/books_info.php?id=372

.jpg)

.png)